In My Seditious Heart, a new volume of her collected essays, Arundhati Roy steps into “the very heart of insurrections” raging against globalization, privatization, and neoliberal capitalism in India and around the world. She asks her readers to emulate the rebels whose resistance she chronicles: to “find the courage to dream. To reclaim romance. The romance of believing in justice, in freedom, and in dignity. For everybody,” she writes. “We have to make common cause, and to do this we need to understand how this big old machine works—who it works for and who it works against. Who pays, who profits.”

In these essays, Roy examines how “the big old machine” works in the contested territory of Kashmir, the militarized forests of India’s heartland, and many places besides. While much of the book focuses on Indian political issues, these essays also explore the rise of patriotic doublespeak after 9/11, the Iraq War, and the Occupy Wall Street movement. Even when Roy writes about topics that may be unfamiliar to American readers, her writing carries clear resonance for anyone worried about the consolidation of authority by governments and corporations; the resulting impact on people, ecosystems, and democracies; and the possibilities and limitations of people’s resistance movements.

These essays, written over 25 years, are united by Roy’s unflinching assessment of the violence and inequality around her, and her search for alternatives to the world we’ve inherited. They’re also united by her style, of course. Roy’s reported essays don’t adhere to the normal standards of journalistic objectivity or present both sides of an issue. Instead, she acts the gadfly, engaging in “a process of constant questioning.” No one escapes her unromantic gaze. Though she writes warmly about people’s movements, including Maoist dissident groups in India, she notes that, if the Maoists came into power, she’d be the first person they’d kill.

Roy’s prose is precise and elegant. Her attention to detail, to “specific people” as well as to forests, rivers, and mountains, is part of a “specific war” against slovenly thinking, fudged estimates, manipulative explanations, ill-advised hagiography, and dead ideology. “The Greater Common Good,” for example, her essay about the gigantic, ecologically devastating Sardar Sarovar Dam in India’s Narmada Valley, examines the impact of the project on just a few of the millions of people it displaced. Take Mohan Bai Tadvi, whose small farm was destroyed by the Gujarat government in the course of building the dam. He waited three years to receive his 2,000 rupee compensation, about $28.75 in today’s dollars, in three installments. By directing attention to small-scale suffering justified in the name of “the greater common good,” Roy works against what she describes as “fascist math”—the ever-shifting estimates of how many millions of villagers will have to be resettled, how many thousands of acres of forest will be flooded, and how much benefit will actually result.

The essay that opens My Seditious Heart, “The End of Imagination,” was written in 1999, two years after Roy won the Man Booker prize for her debut novel The God of Small Things. (She is also the author of the 2017 novel The Ministry of Utmost Happiness.) At the time, Roy found herself uneasily positioned by the media as “a front-runner in the lineup of people who … personify the confident, new, market-friendly India,” even making an appearance on People‘s list of the most beautiful people in 1998.

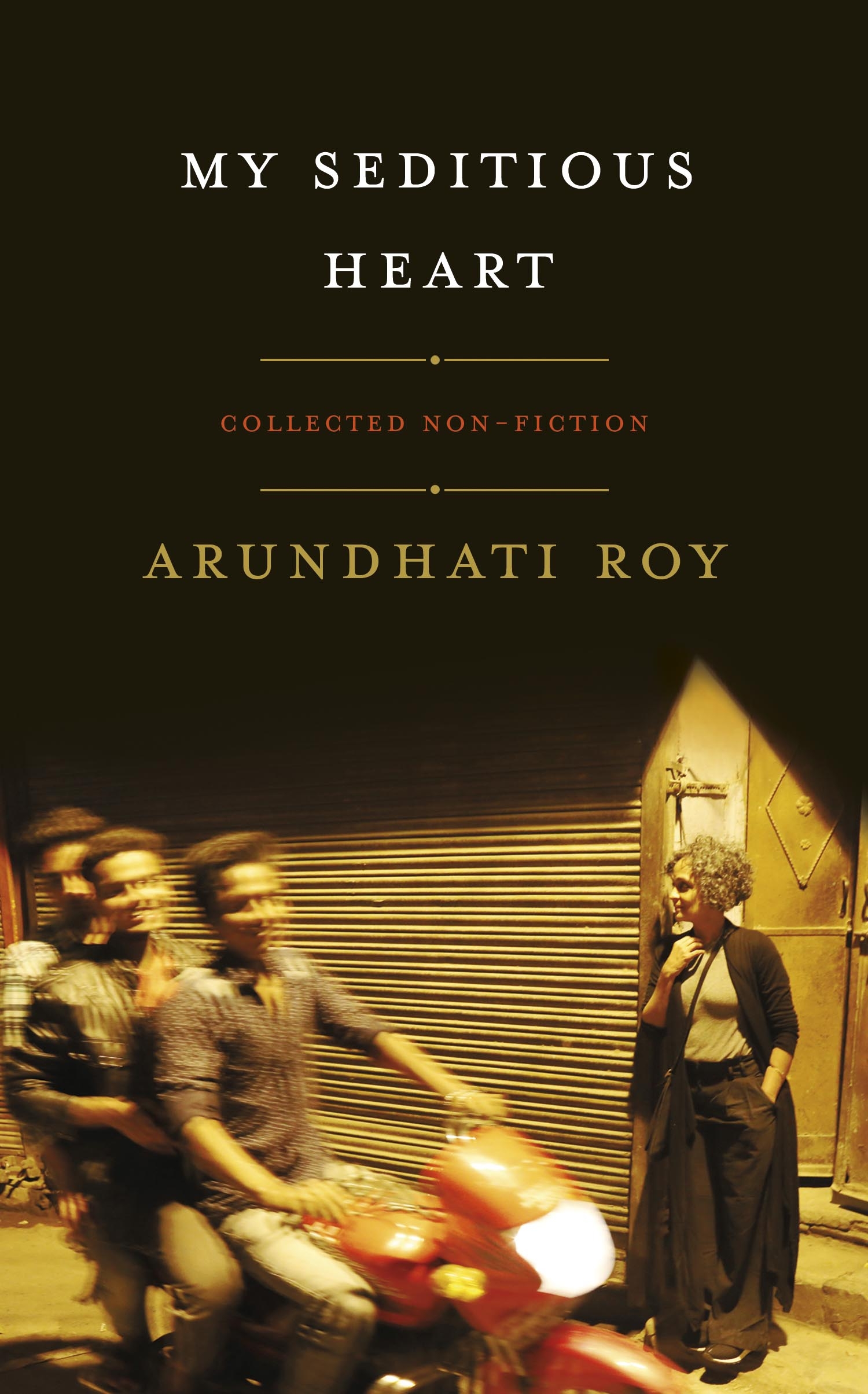

(Photo: Haymarket Books)

Once she began writing about India’s nuclear tests—the focus of “The End of Imagination”—alongside subjects like privatization, and the controversial Sardar Sarovar Dam—Roy became the object of fierce criticism from the Indian government and media. She found herself in trouble with India’s Supreme Court and even served a brief jail sentence. “The backlash to almost every one of the essays when I first published them … was often so wearying that I would resolve never to write another,” she says.

Working my way through this nearly 1,000-page collection, I wondered why she’d kept going. As she writes of Noam Chomsky, “It occurred to me that his marshaling of evidence, the volume of it, the relentlessness of it, was a little—how shall I put it?—insane. Even a quarter of the evidence he had compiled would have been enough to convince me.” In essay after essay, Roy elucidates the core elements of her politics: that globalization and neoliberal capitalism pose an existential threat to human and non-human lives, with their “single idea … [that] Life is Profit.” These systems are incestuously intertwined with governments that use violence to enforce their vision of progress, as in the Narmada Valley—and in Iraq, a country that, Roy points out, was reconstructed after the American invasion to resemble “an American-style capitalist economy,” at the barrel of many guns. As with Chomsky, even a quarter of her examples would have been enough to convince me. So why continue to argue against the near-unstoppable steamroller of global capitalism?

These essays, Roy says, are “my contribution to our collective refusal to obediently fade away.” She sees her work as a corollary to the collective refusals undertaken by people like the Kothi tribe, who, according to Roy, fought the Sardar Sarovar Dam “meter by meter, for decades,” until they were driven from their ancestral lands. Roy wants to force a true accounting of the losses that development and “progress” bring; and to make visible, “even when we lose, whatever it is that we lose—land, livelihood, or a worldview,” she writes. “We must make it impossible for those in power to pretend that they do not know the costs and consequences of what they do.”

Roy employs a technique that union organizer and academic Jane McAlevey describes as “framing the hard choice.” In No Shortcuts: Organizing for Power in the Gilded Age, McAlevey writes that, to recruit a reluctant leader for a union organizing drive, “The organizer … carefully polarizes the conversation so that the worker understands he or she faces a clear and stark choice: Take a risk in order to win the desired benefits, or be safe, do nothing, and get nothing.”

Similarly, Roy deftly polarizes the debates she enters, restoring a sense of humanity to the demonized, the marginalized, and the invisible, and asks if we can still offer our silent consent to the democratic governments who oversee their mistreatment. She urges readers to choose a side, insisting, in Howard Zinn’s words, that “You can’t be neutral on a moving train.”

“We’re standing at a fork in the road,” Roy writes. “One sign points in the direction of ‘Justice,’ the other says ‘Civil War.’ There’s no third sign, and there’s no going back. Choose.”

Roy reminds us that silence and inaction are choices. Trying to crawl out of the moral “crevasse” of the world as it exists is also a choice. “Another world is not only possible, she’s on her way. Maybe many of us won’t be here to greet her, but on a quiet day, if I listen very carefully, I can hear her breathing,” Roy writes.

(Photo: Sondeep Shankar/Getty Images)

Still, even as people’s resistance movements prepare the soil for another world, their enemies are doing the same, as Roy shows. There are many possible alternative worlds—only some of which are more just and equitable than the one we live in now. And resistance movements are not exactly winning the day. While the coalition known as Narmada Bachao Andolan (“Save the Narmada Movement”) successfully pressured the World Bank into withdrawing funding for the Sardar Sarovar Dam, the government of Gujarat stepped in to fill the gap, and the dam was completed. While Roy and the NBA dimmed the glow that had hovered around big dams since former Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru called them “The Temples of Modern India,” similar projects continue to be built. The only victories we see in My Seditious Heart are partial and heartbreaking: They’re the victories of being “beaten down,” but refusing to simply “lie down and die.”

It’s a little grim. At times I found myself identifying with the wealthy friend of a friend who accompanies Roy to a meeting about tribal people resisting corporate development of their land: “‘Someone should tell them not to bother,” he tells Roy. “They won’t win this one. They have no idea what they’re up against…. These good people here should save their breath and find something better to do.”

Roy asks, “When people are being brutalized, what ‘better’ thing is there for them to do than to fight back?”

Roy’s essays about the environmental and human costs of late-capitalist development read as dispatches from a recent past that will also be our future. Climate change threatens to displace more than 140 million people by 2050—another example of the “fascist math” Roy describes operating during the construction of the Sardar Sarovar Dam. The project’s planners dispassionately recommended displacing millions to dangerous urban slums where they had no means of sustaining themselves and might well perish. The danger of “fascist math,” Roy argues, is that it “strangles stories … [and] bludgeons detail.” It blunts our ability to empathize with those who bear the brunt of environmental injustice—a category that will soon encompass many more of us.

There’s a poignant moment when a Maoist asks Roy, “You must have heard about Kotrapal? It’s a famous village, it has been burnt 22 times for refusing to surrender” to the government-backed local militia, the Salwa Judum. I hadn’t heard of Kotrapal. I’m guessing most American readers haven’t either. But its resistance surely holds valuable lessons for the struggles that lie ahead for the rest of the world.

Roy shows that, while resistance is often dangerous and hopeless, it can also be joyful. There’s something gorgeous and seductive about Roy’s depiction of life among the “comrades,” the Maoist guerrillas in the Dandakaranya Forest who resist the Indian government’s violent attempts to convert their land into mines. These “strange, beautiful children with their curious arsenal” walk for days to reach a communal spot to dance together, right under the noses of the police and the murderous Salwa Judum. She doesn’t flinch from describing the diseases and violence she found among the Maoists, and certainly doesn’t advocate that everyone drop their lives to walk in the forest alongside these rebels. “It’s not an alternative yet,” she writes of the guerillas’ approach. “But it certainly has created the possibilities for an alternative.”

Roy refuses to accept the inevitability of development, of globalization, of fascism, of sacrifice by the poorest people for “the greater common good.” Instead, she argues, “Our strategy should be not only to confront Empire but to lay siege to it. To deprive it of oxygen. To shame it. To mock it. With our art, our music, our literature, our stubbornness, our joy, our brilliance, our sheer relentlessness—and our ability to tell our own stories.”

Pacific Standard’s Ideas section is your destination for idea-driven features, voracious culture coverage, sharp opinion, and enlightening conversation. Help us shape our ongoing coverage by responding to a short reader survey.