Plain, direct prose seems like the natural medium for an urgent message like, “We have 11 years to avert climate catastrophe.” But I believe that the struggle over climate change is also, in part, a struggle over how we imagine the future. Will our world continue to be devastated by our dependence on cheap energy, cheap labor, and cheap stuff; and by increasingly destructive “natural” disasters? Or will it look radically different? And if so, how do we imagine the world we hope to bring into being?

The new anthology Here: Poems for the Planet demonstrates how poems can help us do that imaginative work. Poems can “collapse time and space,” to quote the poet Solmaz Sharif. They can reintroduce readers to value systems outside of capitalism’s deadly focus on short-term profits. Their rhythms, beauty, and joyfulness bring us back to a world beyond “this lightbox and its scroll of dread,” writes poet Nickole Brown.

Bob Hicok‘s “Hold your breath: a song of climate change” emphasizes how frighteningly narrow the gap is between tomorrow’s climate disasters and our failure to take action today. The poem opens with a decent summary of the attitude of many Americans toward the climate question: “The water’s rising / but we’re not drowning yet.” Hicok lets the reader linger in this feeling of temporary security only a beat longer: “We’ll do something. / When we’re on our roofs. / When we’re deciding between saving / the cute baby or the smart baby.”

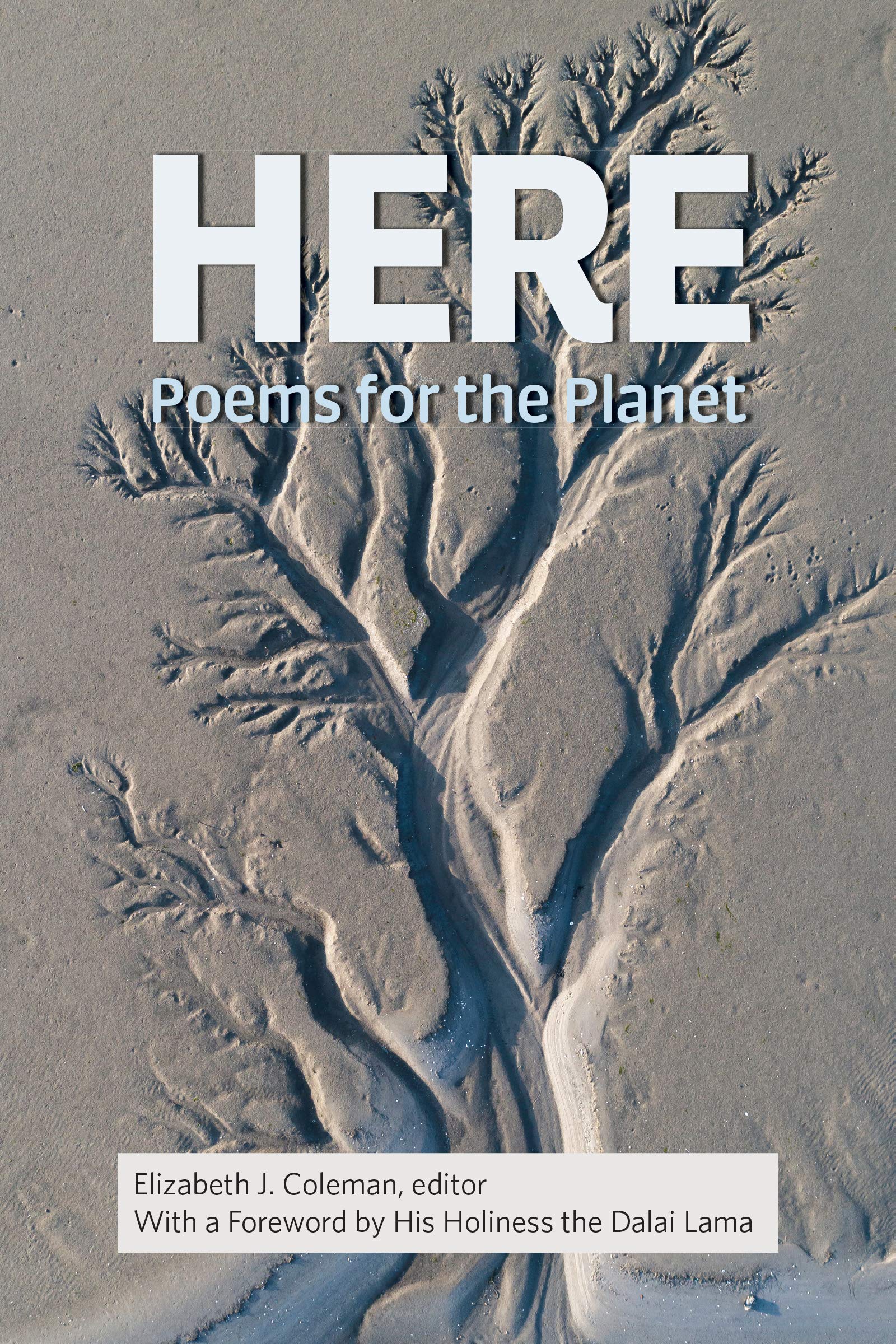

(Photo: Copper Canyon Press)

Hicok brings home the futility of our last-ditch plans to escape climate chaos in his final lines: “We’ll grow wings, we’ll go / to the moon. Soon,” he writes. Climate chaos is coming fast, Hicok’s poem reminds us. If we don’t stretch our imagination toward just, attractive solutions now, we won’t be left with much at all.

In the public sphere, American political imagination is hamstrung by the dominance of short-term economic thinking. We talk about how expensive climate change will be and how it hurts gross domestic product. We talk about the price of the oil that must be left in the ground and about a carbon tax. But the natural world has value beyond what we’ve measured with dollars. Eradicating a species can’t just be written off as the price of progress. In “To the World’s Most Abundant Bird, Once,” Silke Scheuermann describes how Martha, the world’s last passenger pigeon, carried in her “notions / of narrowness and expanse so at odds / with the senior suite at Cincinnati Zoo.” She had once been part of a flock “Thousands of meters wide” that kept Americans “standing for hours in the dark” as the pigeons flew by. If we extended our imaginations as wide as that flock, what kind of human community could we imagine?

Jane Mead’s poem “Money” uses repetition to demonstrate the pervasiveness of corporate control over the environment. Describing a dammed river, she writes,”By then the water / didn’t belong to the salmon anymore, by then // the water didn’t even belong to the river. / The water didn’t belong to the water.” But the poem’s repetitions also makes the current state of nature sound strange. Mead opens the door for readers to ask why we’ve allocated control over resources in this way, and how it might look for things to be otherwise.

I began this anthology a few hours before going on a “Toxic Tour” of Northwest Indiana. I saw the BP oil refinery in Whiting, the dusty ArcelorMittal steel plant in East Chicago, and one of the country’s most polluted waterways, the Indiana Harbor Ship Canal. I thought of Tim Seibles’ “First Verse”: “Look / what we’ve done,” he writes. “With all / we knew. / With all we knew / that we knew,” echoing Paul Celan’s anguished post-Holocaust poem, “Zurich, At The Stork.”

The poems in Here reminded me that humans are capable of many different kinds of creation. Each poet had crafted a beautiful thing they hoped would move me, that expressed a tenderness toward human weakness, and a fierce desire to remain in this world and testify to its wonders. “I admit the world remains almost beautiful,” Seibles writes. “Despite the great predatory surge of industry, / two human hands still mate like butteries / when buttoning a shirt.”

Though the individual poems in Here are powerful, the collection is weakened by some editorial choices. Its fourth section consists of poems by poets ages six to 18. I was excited to read these poems, since young people have been some of the boldest and most persuasive voices on climate action. Unfortunately, this selection of poems is underwhelming. While they demonstrate poetic skill and sensitivity to the natural world, they lack the fire, humor, and directness of the youth climate organizers I follow on Twitter and whose op-eds I read in Teen Vogue.

The kids’ poems are nature poems, some of which include both “the beautiful bird,” and “the bulldozer off to the side … destroying the bird’s habitat,” in the words of eco-poet Juliana Spahr. But none of them are really political poems. There’s no sense of vehemence or fury or blame in a poem like Katie Friedman’s “Haiku”: “Hit rewind and / the flowers will bloom bright again, / rain will revisit the sky.” There’s no urge toward action. It’s written from the future, when the worst has already happened, the drought come and the flowers gone. Instead of demands, there are vague blandishments: “Nature has a voice / If only you’d listen,” concludes “Voice,” by Lauryn Brown.

I know young people are out here writing fiery political poems. I know young people can talk about climate change in politically sophisticated ways. So where in this anthology are those poems? Whose idea of youth does it flatter to include so many poems about young people’s connection to the sky and caterpillars, but none that include words like “fossil fuels” or “extinction”?

Outside of the youth poets section, there are very few works by poets under 35—poets who are young enough to expect climate devastation in their lifetime, but old enough that readers can expect them to write with adult sophistication and political analysis. Using this list from the website of Elizabeth J. Coleman, who edited the anthology, I did my best to determine the ages of the 129 contributors to the anthology. Twenty-two were classified as youth poets. Of the remaining 103, only two were under 35.

I imagine the gap is mostly a result of the fact that Coleman is of an older generation; she describes herself as “a child of the ’60s.” But it’s a shame to have so little work by this diverse and politically engaged cohort, who have helped bring a larger audience to poetry—the larger audience Coleman says in the introduction that she wants for this anthology. I wanted to know: How have the major political events of their generation formed their understanding of our next great challenge—climate change? How has it shaped this cohort that nearly every year of their lives has been record-breakingly warm?

Coleman frames the anthology around a set of emotional reactions she hopes to inspire in the reader. I found it to be an off-putting choice, one that foreclosed rather than opened possibilities for readerly response. We are supposed to begin the anthology by recalling “the beauty of our earth” and appreciating “anew our ‘peaceful, living earth,’ as Valdemar á Løgmansbø writes,” Coleman says. Sections two and three “bring to life the peril that the earth and its creatures face,” and “[ask] us to mourn.” Section four, the youth poets section, is meant to bring us back toward hope. In section five, the “bracing, energizing, and inspiring” is supposed to take place; then comes an Activist Guide written by the Union of Concerned Scientists. If all goes as planned, the reader will have experienced a precise emotional symphony, from love to grief to hope to action.

In the face of ecological catastrophe, Coleman wants poetry to be useful. She’s also donating a copy of this anthology to every member of Congress. She’ll direct all royalty payments to the Union of Concerned Scientists. I can’t blame Coleman for wanting to enlist poetry in the struggle for a habitable Earth. But “Love is letting the world be half-tamed,” Jennifer Grotz writes in “Poppies,” and I think the same applies to readers, whose unpredictable, sometimes messy reactions to poetry should not be micromanaged.

“Poetry / isn’t revolution but a way of knowing / why it must come,” Adrienne Rich once wrote, and to my mind that is a better way to think about the work that this anthology can do. It will not do as much as Big Coal’s millions to swing a congressman’s vote. But these poems can help urge individual readers toward a place where our love and grief and hope for our world is so strong, we can’t help imagining a different future for it.

Pacific Standard’s Ideas section is your destination for idea-driven features, voracious culture coverage, sharp opinion, and enlightening conversation. Help us shape our ongoing coverage by responding to a short reader survey.