With the rise of President Donald Trump, we have seen a deluge of what might be termed “Real America Reporting,” whereby journalists seek out supposedly typical middle-American voters—generally white, generally rural, often eating in diners—in order to conduct sympathetic interviews and glean political insights. Claire Galofaro at the Associated Press went into Kentucky in 2017 and reported that “In the Heart of Trump County, His Base’s Faith Is Unshaken.” Terrence McCoy at the Washington Post encouraged readers to empathize with the plight of white factory workers in Pennsylvania who feel angry and alienated because most of their co-workers speak Spanish. Salena Zito has become famous for Trumpian man-on-the-street interviews, from which she has concluded that the president is a righteous populist hero. (Zito’s anecdotes are almost uniformly so convenient and poorly sourced that she’s been credibly accused of serially fabricating quotes.)

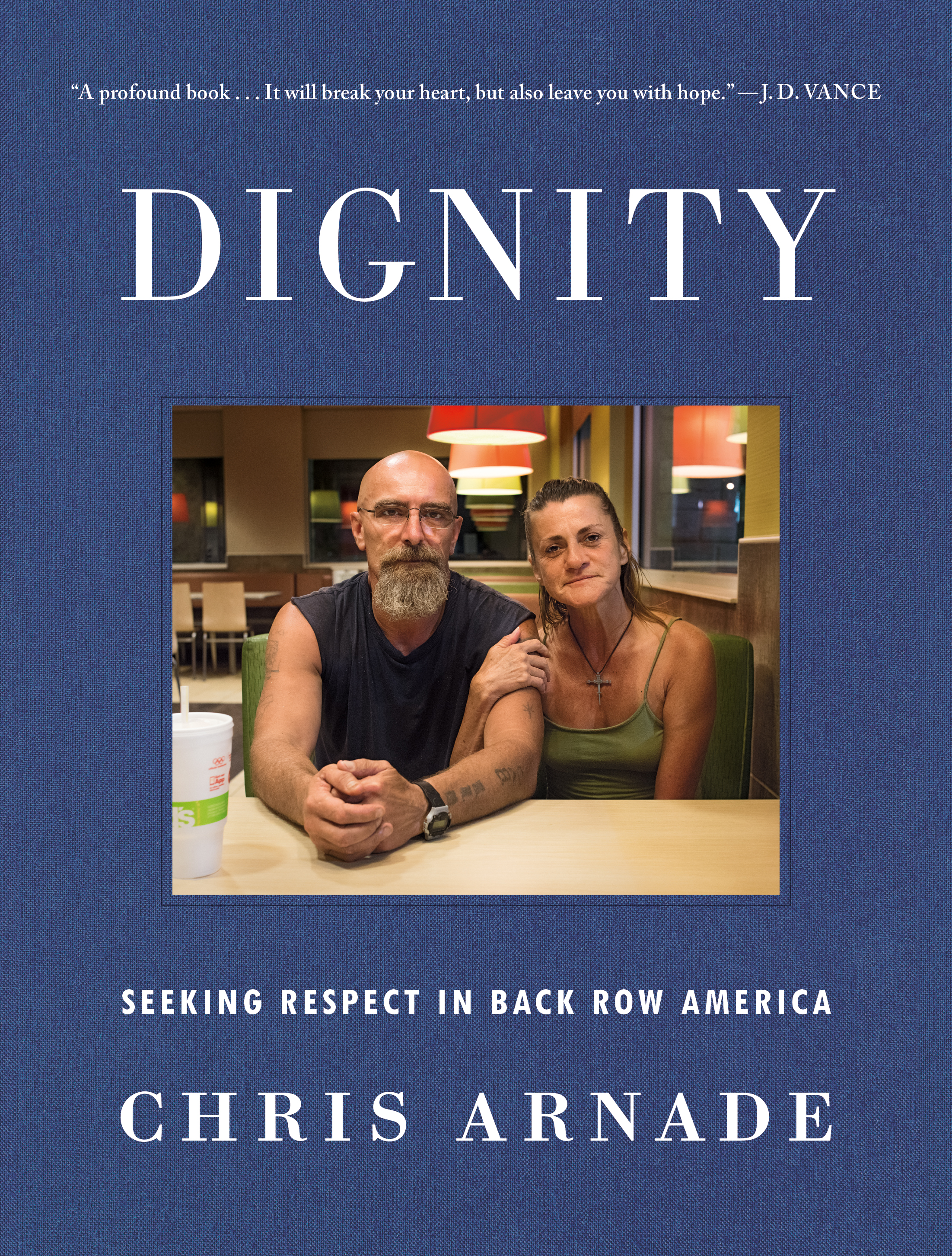

Of all the Real America Reporters, writer and photojournalist Chris Arnade is easily the most thoughtful, the most dedicated, and the least taken in by Trumpian talking points. His new book, Dignity: Seeing Respect in Back Row America, which includes generous galleries of his photos, is a careful, quiet, admirable effort to understand and chronicle the lives of people living in de-industrialized and impoverished communities across the country.

Arnade’s thoroughness, and his respect for his subjects, stand as a rebuke to reporters like Zito, who casually pull into a gas station or diner for quotes and then drive on. But for all its virtues, Dignity still ends up, almost despite itself, reaffirming the preconceptions and some of the reactionary analysis of Real America reporting. Arnade demonstrates the virtues of journalism based on empathy and personal commitment. But he also shows that these virtues alone are insufficient when they’re not supported by a broader historical and political analysis.

Part of what makes Arnade different from many of his peers is that his reporting was not initially inspired by Trump’s campaign. He began the research that would become Dignity in 2011, when he was still working as a bond trader on Wall Street. After 18 years in the financial sector, Arnade increasingly felt his job was hollow and pointless. He began to take long walks through the impoverished Hunts Point neighborhood in the Bronx, getting to know some of the people who lived there, taking their pictures and occasionally helping them with money or transportation. His Wall Street career seemed less and less important, and eventually he abandoned it to pursue journalism full-time.

(Photo: Courtesy of Chris Arnade)

Real America Reporting often frames white, rural Trump voters as uniquely disadvantaged, or as synonymous with working-class Americans. Arnade never makes that mistake. Much of the book is devoted to black communities and other communities of color in urban neighborhoods. Arnade always remembers that America’s poor are a multiracial group.

In one telling anecdote, Arnade is in Cleveland when Trump accepts the Republican nomination. He talks to a number of white workers, one of whom endorses Trump because “guys like me who work for minimum wage are being screwed.” Arnade also reports, though, that the one black man in the group was less thrilled. “That man [Trump] is a racist,” the man said straightforwardly. “That man doesn’t like me. That man doesn’t like any black person.”

Arnade was able to hear difficult conversations like this because he put in the time. He spent days or weeks on Milwaukee’s North Side; in Cairo, Illinois; in Selma, Alabama. He stayed long enough in each place to form real relationships with the people he met and talked to.

Arnade also consistently, and impressively refuses to judge his interlocutors. His descriptions of sex workers and addicts are always matter-of-fact and respectful—perhaps abetted by his own experiences with addiction, which he discusses early in the book.

One of Dignity‘s best sections is Arnade’s explanation of the value of McDonald’s. Fast food is often despised by the affluent. But for poor communities, the franchise is a consistent, reliable gathering place, where food is cheap and no non-profit administrator is evangelizing, or policing drug use. Perhaps my favorite of Arnade’s photographs shows a couple at a McDonald’s table, leaning into each other, nose to nose, their food scattered in front of them, the woman holding a partially eaten burger in her hand. It’s sweet and serene. They look like they’re home.

(Photo: Penguin Random House)

Arnade’s intimate perspective is one of the book’s great strengths. But it trips him up when he moves to broader analysis.

Arnade frames class division in the United States in terms of literal classrooms. He argues that “front-row kids” like himself—highly educated and mobile over-achievers—have abandoned “back-row kids,” who lack access to education and paths to career success. The current system, Arnade argues, “says you cannot reject anyone based on the color of their skin, but you can and should reject those without the proper credentials, and minorities rarely start with the proper credentials.”

Front-row kids, Arnade says, need to respect back-row values. Front-row kids shouldn’t make fun of people’s religious beliefs. They shouldn’t tell people to move away from their homes to get jobs. Home is where people’s families and community are, and they are right to value them. In short, liberal elites have lost touch with faith, with rootedness, with America. In that vein, Arnade at times seems to be advocating as much for the spiritual renewal of the front-row kids as for the economic renewal of the back-row ones.

The problem with this reading isn’t that Arnade is wrong, exactly. He’s right to puncture the myth of meritocracy, and right to argue against the stigmatization of the poor. But the lack of broader historical context in his discussions, coupled with his conservative nostalgia for a grounded meaningfulness, creates a fog of vague collective guilt that makes it difficult to see the actual mechanics of how the back-row kids actually get oppressed.

For example, Arnade repeatedly critiques a front-row fixation on education and credentialing. But he grapples only sporadically with the real history of segregated schooling in the U.S. Affluent white Americans have deliberately worked to deny educational opportunities to poor black people for hundreds of years. White parents and governments have historically set up systems that pillage black communities for funds to educate white children better—a practice that continues today, as Noliwe Rooks documents in Cutting School: Privatization, Segregation, and the End of Public Education. The class divide isn’t caused by the failure of the wealthy to appreciate the less education-driven values of the poor. It’s caused by wealthy people who actively hoard educational resources for themselves. What Arnade frames as a difference in values is actually a difference in power.

Similarly, Arnade’s discussions of racism often seem to have emerged in a historical and theoretical vacuum. He worries that affirmative action will inflame divisions between front-row and back-row kids. He takes little time to acknowledge that all efforts to redress racial inequities, from busing to voting rights to ending slavery, have been met with white backlash.

Arnade thinks that poor white people are driven to racism because society treats them with too little respect. He says that white identity politics flourish because “the back row has been left with little to take pride in that doesn’t need credentials.”

This analysis would be convincing, perhaps, if white supremacy were a new ideology. But, obviously, it is not. White identity politics has been a powerful force in America since before there was an America. Many white politicians, white pundits, and white activists work unceasingly to keep it salient.

A lot of mainstream white Americans have always seen the success of others—like that of President Barack Obama—as a threat to their pride. This isn’t a new phenomenon, and it isn’t one that we can solve simply by assuring people that it’s OK not to have a college degree. Numerous studies have shown that Trump voters were characterized and motivated by their racism, given that they were not particularly economically disadvantaged compared to their peers. Yet Arnade simply repeats the same tired talking points about how economic disadvantage strengthens white identity. He doesn’t even mention the relevant research that complicates his account, much less dispute that research.

Arnade’s book ends with a call for tolerance. “We need everyone—those in the back row, those in the front row—to listen to one another and try to understand one another and understand what they value and try to be less judgmental.” It’s a heartfelt plea, and Arnade’s efforts to live by it are admirable.

But Dignity also shows that listening without judgment isn’t enough to point a way toward better policies or better lives. You may find Real America in a diner or a McDonald’s, but without the social and economic context provided by historians and scholars, what you end up hearing will be limited. Racism, classicism, and bigotry are pervasive; they can shape our ideas and emotions even when we guard against them. Without an understanding of the history and logistics of injustice, it’s easy to wax nostalgic for a better past, or to see hatred as some sort of economic accident, rather than a deliberate political program. Credentials are undoubtedly overrated. But whether you’re in the front row or the back row or have left the classroom altogether, knowledge is power.

Pacific Standard’s Ideas section is your destination for idea-driven features, voracious culture coverage, sharp opinion, and enlightening conversation. Help us shape our ongoing coverage by responding to a short reader survey.