In 1969, writing a new preface for The Chicago Race Riots, a collection of articles published by Carl Sandburg on the eve of deadly violence in the city during the summer of 1919, anti-segregationist journalist and editor Ralph McGill asked: “How much do cities, a people, a nation learn in 50 years?”

His conclusion: “Not much.”

Even half a century after the Chicago race riots, it seemed that the city hadn’t absorbed the lessons of that infamous week of violence that left 38 dead during July and August of 1919. The murder of Eugene Williams, a 17-year-old black teenager who was stoned by a white man after drifting over the invisible barrier between black and white beaches on the Lake Michigan shoreline, had provided the immediate spark for the deadly events to come. But even before that day, conditions stoking racist hatred in the city had been clear for years.

Some of these factors, including the overcrowding of a booming black population into substandard housing and increased competition for jobs after the end of World War I, were documented in a report sponsored by Illinois Governor Frank Lowden, The Negro in Chicago: A Study on Race Relations and a Race Riot, published in 1922. It was a detailed, unsparing document, written by six white and six black men deemed credible representatives of their communities, that offered no easy solutions but plenty of discomforting observations on the state of black life in Chicago. Poet and University of Chicago professor Eve Ewing found this document while writing her second book, Ghosts in the Schoolyard: Racism and School Closings on Chicago’s South Side, and while it appeared only briefly in that book, Ewing was unable to resist a deeper exploration of the text of The Negro in Chicago.

Struck by the poetic language in what was ostensibly a sober analysis of the deadly events, Ewing was inspired to write 1919, a new collection of poems that meditate on the ways in which the unlearned lessons of 1919 remain with us today. Her reflections on events like the sentencing of police officer Jason Van Dyke in the killing of Laquan McDonald, and the death of 739 poor and elderly Chicagoans in a 1995 heat wave, serve as painful reminders that the conditions that produced the deadly events of a century ago are still at work today. As Ewing writes in the introduction, describing black life in Chicago over the course of the 20th century: “So many things struck me as being either radically different or completely unchanged.”

In 1919, Ewing reimagines the 1922 Illinois report as “an old tapestry with loose threads sticking out,” a look into the past whose unfinished edges urged Ewing to “see what new thing [she] could weave.” Ewing spoke with Pacific Standard to discuss the riots’ place in Chicago’s history, the power of poetry as a form of historical inquiry, and what it will take to learn lessons from these events, a century on.

In the introduction, you say that the 1919 Chicago riots are rarely discussed as part of the city’s story. Given that you’re intimately familiar with Chicago’s past, what does that silence say about the wider stories we tell ourselves about our city’s history?

I think that some of it is reflective of a general lack of attention to that period of history. I don’t know why, but I feel like a lot of Americans don’t have much awareness of that period. In particular, thinking through the lens of black history, a lot of people act like there was slavery, and then there was the Civil Rights Movement, and then Barack Obama. In between, nothing really happened.

I’m not really sure why that is. I wonder if some of it has to do with the lack of a kind of redemption narrative around it. If you wanna talk about slavery, you can talk about emancipation, and if you wanna talk about Jim Crow, you can talk about the Civil Rights Movement. But from this period in time, there’s not a clear, triumphant narrative that emerges: “And then the good people came, and they fixed all the bad stuff.” There’s an incredible period of violence, and then people said that we should do something about it, and then nobody really did anything about it, and that was the end. There aren’t clear heroes, and there isn’t a clear arc of redemption.

You mention the poetic sense you got from The Negro in Chicago report. As part of your historical inquiry, what was the specific power of taking a poetic approach to these events, rather than doing something more traditional or scholarly?

I think all poets have this in common, and it’s something that poets share with social scientists, who are intrigued by small moments in meaning-making in everyday life that escape other people’s obvious notice. I think that the work of social scientists and poets is to notice things other people aren’t really noticing, and what I think I noticed in this text was the artfulness of the language, and the level of craft that went into it, which seemed surprising to me in the context of this government document. I wanted space to play there with the language, more than I necessarily wanted to do a critical interrogation of the history itself. I also felt that, because the thing I was writing about was something that is so under-discussed, poetry would be a useful medium as for people to get some of the basics under their belt.

In the introduction to Carl Sandburg’s collection of articles published around the riots, editor Walter Lippman argued that those articles “will move those who will allow themselves to be moved…. Moved not alone to indignation, though that is needed, but to thought.” How do you hope your work will move people?

There are a couple of things I’m hoping to move people to do. One is that we live in a time where people have an unprecedented opportunity to seek out information themselves, and I wanted this to be an entry point to then seek other sources. I also hope to invite people to think critically about space, and the history of the spaces that we occupy. Something that was so profound to me about reading the report, beyond the poetic language, was the spatially grounded nature of the report, because the murders are happening in places I’ve physically inhabited, often with some frequency, spaces that everyday Chicagoans might pass by without ever understanding that they were sites of this important event, often a site of extreme brutality.

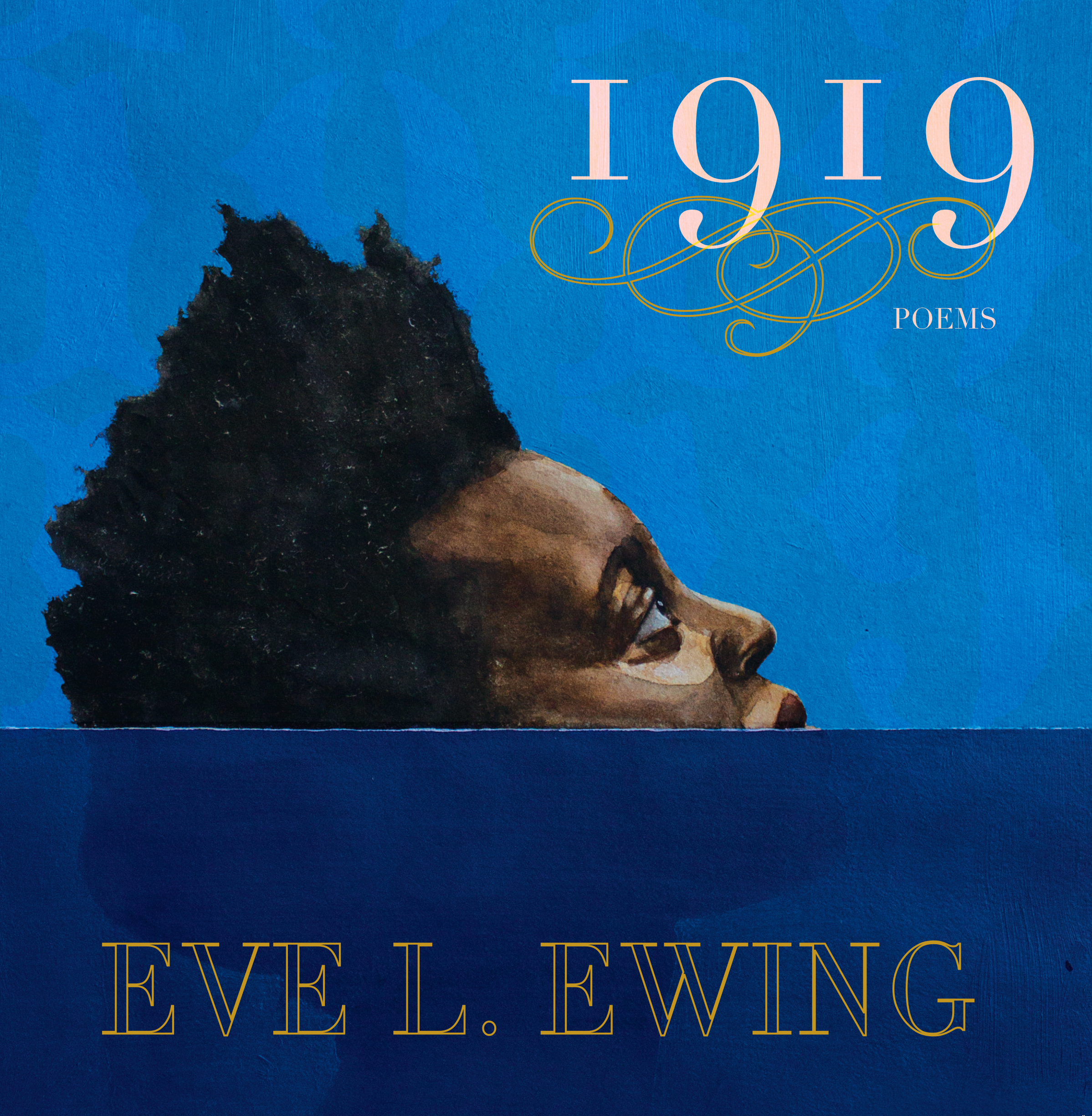

(Photo: Haymarket Books)

That’s a national conversation we’re having about what it means to occupy indigenous lands, thinking about what it means to live among confederate statues. We’re in a time where we’re critically engaging with understanding the histories of the places where we move and work every day, and so I want to invite people to do that as well.

Your collection thinks a lot about borders, and the ways in which the events of 1919 solidified the racial boundaries that now seem immoveable in the city. Why was it important to focus on borders in this way?

In the last few years, as borders have taken on a magnified visibility in our public discourse, I’ve been moved by some of my close friends who are writing about them. People like Safia Elhillo, José Olivarez, and Fatimah Asghar are all engaging in these questions of border-making and border defiance. For those of us not raised in a transnational or immigrant context, it can be easy to think that those questions are not our questions, and I think that what [those authors’] work reveals is that these are omnipresent questions that all of us should be considering.

Right. Especially in a place like Chicago, where spatial segregation is so obvious, it’s still striking how many people don’t view it as an important question, when these divisions have shaped the city for over a century.

The thing is that if you’re black and live in Chicago, as much as people have this stereotype of never getting off your block—there are definitely people that never get off their block—but other people constantly have to engage in predominantly white spaces in order to work, access services, get groceries. All of those things require movement into and out of these spaces where whiteness is normative, and you’re reminded that you’re a visitor, in some cases an unwelcome visitor, whereas if you’re a white Chicagoan it’s very possible that you’ll never have to acknowledge or face the existence of these other parts of the cities that, as you say, stretch on for miles and miles.

Your book reminds us that these boundaries aren’t fixed by fate but are products of historical circumstances. Why is that reminder so important to this story?

If anything, that’s the thread between this book and some of my other work. When I give talks about my second book, Ghosts in the Schoolyard, which engages quite a bit with questions about segregation from a more sociological perspective, I frequently joke about the “segregation fairy.” People think that this segregation fairy just went around and cast a spell of segregation everywhere, instead of thinking of these [boundaries] as man-made artifacts.

It’s important to think about these histories, because thinking about the critical moment of intervention, where human beings made decisions that resulted in our present reality, necessarily reminds us that human beings did that, and these were not divine acts. It would be preferable to act as if they were, because then you could relieve anyone of culpability, and that’s part of why I hope to invite people to understand history better: in order to interrogate how things could be otherwise.

Pacific Standard’s Ideas section is your destination for idea-driven features, voracious culture coverage, sharp opinion, and enlightening conversation. Help us shape our ongoing coverage by responding to a short reader survey.