One morning in October of 2017, Karen Fies woke up when her home’s electronic devices began making clicking sounds. It was 1 a.m. First she heard the power shut off, then she smelled smoke, and although her husband Brian was initially skeptical that the nearby wildfire in Calistoga, California, had reached their neighborhood, Karen convinced him they should pack their car. Over the course of 15 minutes, the couple grabbed all the cherished possessions they could think of: a drawer of important papers, the dog and cat, and their daughters’ most beloved stuffed animals, plus a few other possessions. Then they raced to Karen’s office in Santa Rosa, California, which has a generator and Wi-Fi, to spend the night.

By one hour later, according to their best estimates, their neighborhood had been reduced to smoldering rubble.

The Tubbs Fire left many families with stories like this one, but few were shared as widely as Brian and Karen’s. Just a few days after his home was destroyed, Brian, a cartoonist and writer, posted a hastily composed comic on his personal blog. Titled “A Fire Story,” it followed the couple from their escape, to the moment when they saw their home had been decimated, to a trip to Target to restock essentials. The comic racked up about 700,000 unique views in a few days, and by a couple of weeks after the fire, that number had reached three to four million.

“It didn’t take too long for my publisher to contact me and say, ‘Hey Brian, no pressure, but if you ever want to turn it into a book, we’ll publish it,'” Fies says. “I wanted to, because I knew there would be a lot more story to tell.”

The resulting graphic novel, A Fire Story, offers Fies’ story alongside those of five other people affected by the fire. Fies, a former reporter for a daily newspaper in Central California, says he interviewed other Tubbs victims because he wanted to offer readers more viewpoints: “I knew my perspective was limited to what had happened to me and my middle-class life in a middle-class home,” he says. Fies intersperses these personal narratives with information about how the fire moved and why it was so destructive; how local emergency alert systems failed; and how survivors created groups online to share vital information—all so he could to “tell the whole story of the fire,” as he puts it.

Pacific Standard caught up with Fies recently to discuss how he decided to turn the tragedy into a book, what he learned from interviewing other fire victims, and why remembering what he lost is a “fresh stab to the heart every day.”

Tell me about the morning after the Tubbs Fire, and how you came to write about it.

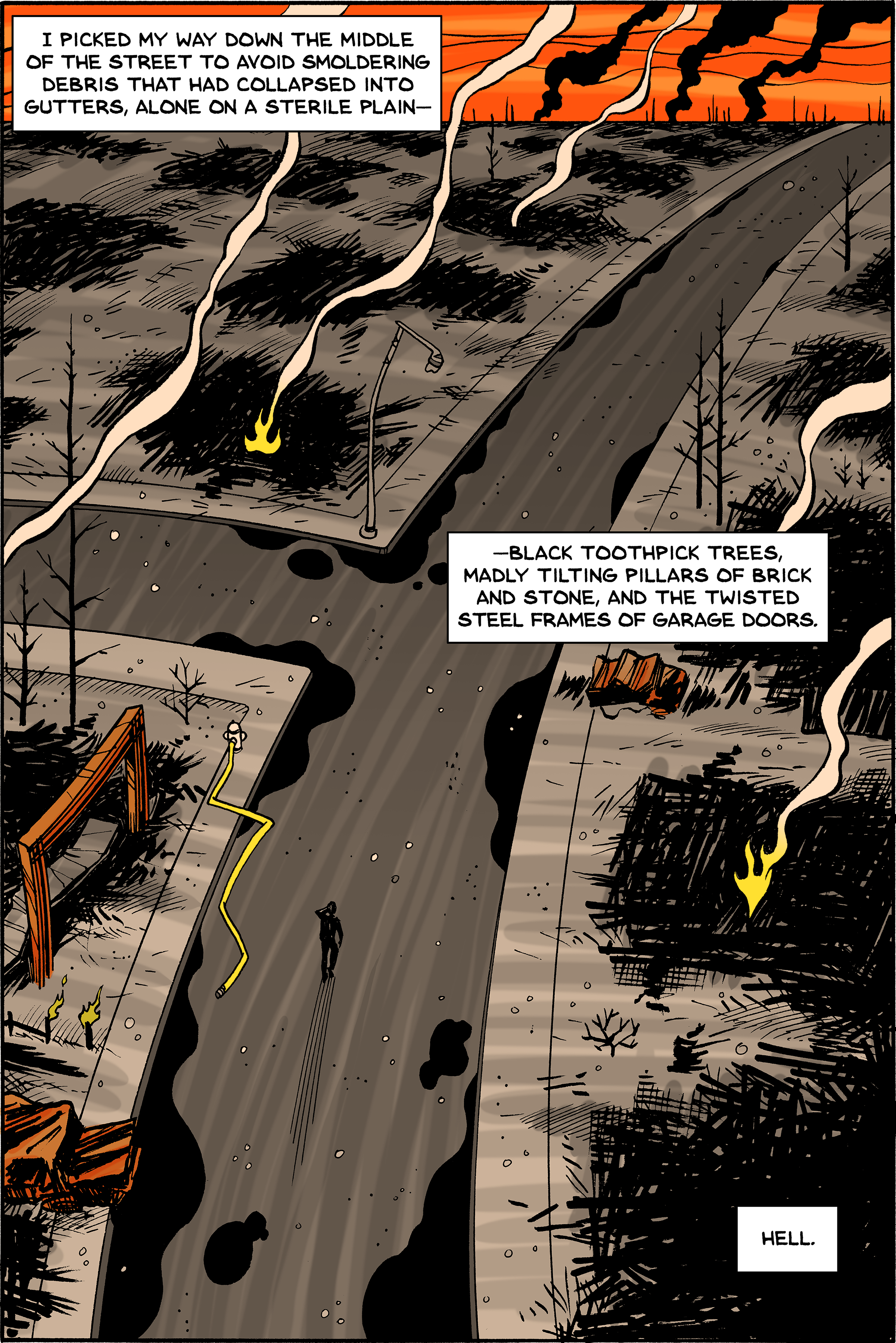

The morning [after the fire], just after dawn, I set out to walk the neighborhood and see what I could see. I really thought the neighborhood would be fine; I had no expectations that it would be destroyed. As I wrote in the comic, I walked through a neighborhood that was just fine, and I thought, ‘Well, this is great, this isn’t going to be a problem,’ and then I turned a corner and saw a desolate plane still smoking with little fires here and there. It looked like a nuclear bomb had gone off.

Even then, I was very aware that I was witnessing an extraordinary event and I felt an obligation to pay attention to what was going along. Even when I knew my house was gone, I knew I was going to be writing about it, I knew I’d be telling the story. I think it goes back to my first job out of college, as a newspaper reporter. I did that for about three years at a small daily in Central California, and I think that’s how I process things: noticing them and taking notes. I took pictures as I walked in because I knew I’d be drawing these things later.

(Photo: Courtesy of Brian Fies)

How is this book different from past projects where you’ve addressed news events in comic form?

I’d published two graphic novels before, and the first one is the most relevant: It’s called Mom’s Cancer. My mom was diagnosed with cancer in 2003, and I decided then that telling our family story as a comic was the way to do it because as my mom was starting her treatment, my family and I just kept getting hit by these surprises. I wanted to tell the story of this event and also draw a roadmap for anyone who might be coming behind us. [I wanted] to say “When you’re diagnosed with cancer, these might be some of the things that happen too.”

So I did a very similar thing: I put Mom’s Cancer online as a webcomic, it got some notice and won some awards and got published as a book by Abrams in 2006, and it’s still in print and taught in medical schools these days. So this idea of treating a very serious subject in comic-strip form was not alien to me when my house burned down. It was sort of the first thought I had: “This is my next graphic novel.”

By interviewing other people and telling your own story, did you learn anything about how you yourself were dealing with the trauma of the Tubbs Fire?

This isn’t a direct answer to your question, but the first thing I noticed was a lot of commonalities among us. For example, with everyone I talked to, everyone thought they would be gone from their home for two days—not one day, not three days, two days. So they did exactly what I did: They packed two pairs of underwear, two pairs of socks, and an extra shirt. I thought that was really interesting: Why two days? That was a weird quirk of the mind.

Another thing that really impressed me was that so many people I talked to—some I interviewed, some I didn’t—expressed the idea that, as bad as they had it, other people had it worse. We certainly felt that, my wife and I. We managed to save a few things; other people had 10 seconds to get out of their home and didn’t save anything. Other people didn’t have insurance, other people were a lot worse off than us. So you talk to these people—and a couple of the people I interviewed are quite poor—who had nothing after the fire, and they’re helping other people because they recognize that other people are even worse off than they were. And I thought that was just extraordinary; it really said something about their humanity and their spirit.

So I guess the answer to your question is that I realized in talking to other people that we had a lot more in common than I thought, that we were all in the same boat. A year after, you have a conversation with someone who’s been through it and you’re saying the exact same things in the exact same words. And it’s really a little uncanny.

What was the thinking behind your indictment in the book of how emergency response systems reacted to the Tubbs Fire?

I didn’t dwell on it, but it really needed to be talked about, particularly because it’s a lesson that other counties or jurisdictions need to learn. Sonoma County was not as prepared for this as it could have or should have been. I think it’s an issue of: “You had this big red button and you could have pushed it; you didn’t push it. Why?” Somebody knew my house was going to be destroyed that night; why didn’t anyone tell me?

(Photo: Brian Fies)

Did you have a specific reader in mind while writing the book—say, a reader who’s not in California and unfamiliar with wildfires here, or people in your neighborhood?

All of that. It was very important to me and my publisher that this not just be a regional book that might sell a few copies in Northern California, or might just do well on the West Coast. I wanted readers to relate to it if they had never been here, if maybe if they had experiences with tornadoes, hurricanes, or blizzards and maybe not fire, because there’s a lot of commonality between any sort of disaster. Anyone who’s been through anything like this is going to relate a lot to what happened out here, I think.

Have any fire survivors read the book yet?

Yes, many.

How did they react?

I get two reactions that mean the most to me: One is people who have been through it, other fire survivors who tell me I got it right. And people who haven’t been through it, on the other side of the country, who tell me that my comic helped them understand what it was like to be here, like they got it and understood. That’s what I hoped to achieve.

What can a graphic novel bring to a story of the Tubbs Fire that a book or art exhibit couldn’t?

The reason I work in comics—because I can also write a feature story or what have you—[is that] I find comics a very powerful storytelling medium. It excels at things like metaphor and symbolism and tapping into the brain. When a comic’s really working right, the reader absorbs the story before they even know they’ve read it. It’s like it’s a direct tap from the cartoonist’s brain to the reader’s brain. It’s a very powerful medium, and readers tend to project themselves into the story very, very easily. The abstractness of a comic and a cartoon drawing, that invites people to come into it and fill in details from their own lives.

How has life been since the Tubbs Fire?

My wife and I found a rental in a town off the Russian River, and we lived there for six months, and we are now in another rental whose lease expires in April that’s about 10 minutes from our rebuild. We’re rebuilding our home on the same lot. Many of our neighbors say they’re coming back, almost all of our neighbors, which is a little unusual and means a lot to us; a lot of neighborhoods disintegrated as everyone went their own ways. Our house is actually pretty far along, and if everything goes as planned, we’ll be in it within a couple of months.

A big part of the story of the Tubbs Fire is how uninsured everybody was, and the different experiences people had with their insurance companies, both good and bad. Ours has been mixed but generally good. But we still don’t know how we’re going to afford this house we’re rebuilding; we’ll figure it out. But we’re OK. It’s difficult. It seems like every day something will come up, and my wife and I will just look at each other and we’ll say: “You know what we lost? You know what we forgot to grab?” And we’ll just think of something, and it’s like a fresh stab to the heart every day. So I don’t think you get over it; I think you just build a new, different life than you had before. Because you never get the old one back, that’s for sure.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Pacific Standard’s Ideas section is your destination for idea-driven features, voracious culture coverage, sharp opinion, and enlightening conversation. Help us shape our ongoing coverage by responding to a short reader survey.