“I’m self-made. I grew up in the projects in Brooklyn, New York. I thought that was the American dream.” That was billionaire-turned-maybe-presidential hopeful Howard Schultz, recently tossing around a clichéd phrase that means, per Merriam-Webster, “a happy way of living that is thought of by many Americans as something that can be achieved by anyone in the U.S. especially by working hard and becoming successful.”

Yet neither that definition of gritty individual achievement, nor Schultz’s similar emphasis on being self-made, fits with the phrase’s original meaning. Around the early 1900s, “the American dream” spoke to something less capitalist, less self-involved: the broad ideal of democratic and economic equality for all.

Two years before Schultz was known for much beyond his Starbucks empire, another phrase began to be batted around political discourse again: “America first.” In his inaugural address in January of 2017, Donald Trump seemed officially to embrace the phrase, which he had first used a year earlier, saying: “We assembled here today are issuing a new decree to be heard in every city, in every foreign capital, and in every hall of power. From this day forward, a new vision will govern our land. From this day forward, it’s going to be only America first.”

While pundits eagerly traced the phrase back to the 1940s, to Charles Lindbergh and the far-right-friendly America First Committee, it had in fact appeared even earlier than that: In the early 20th century, “America first” was a popular slogan used to argue for American isolationism.

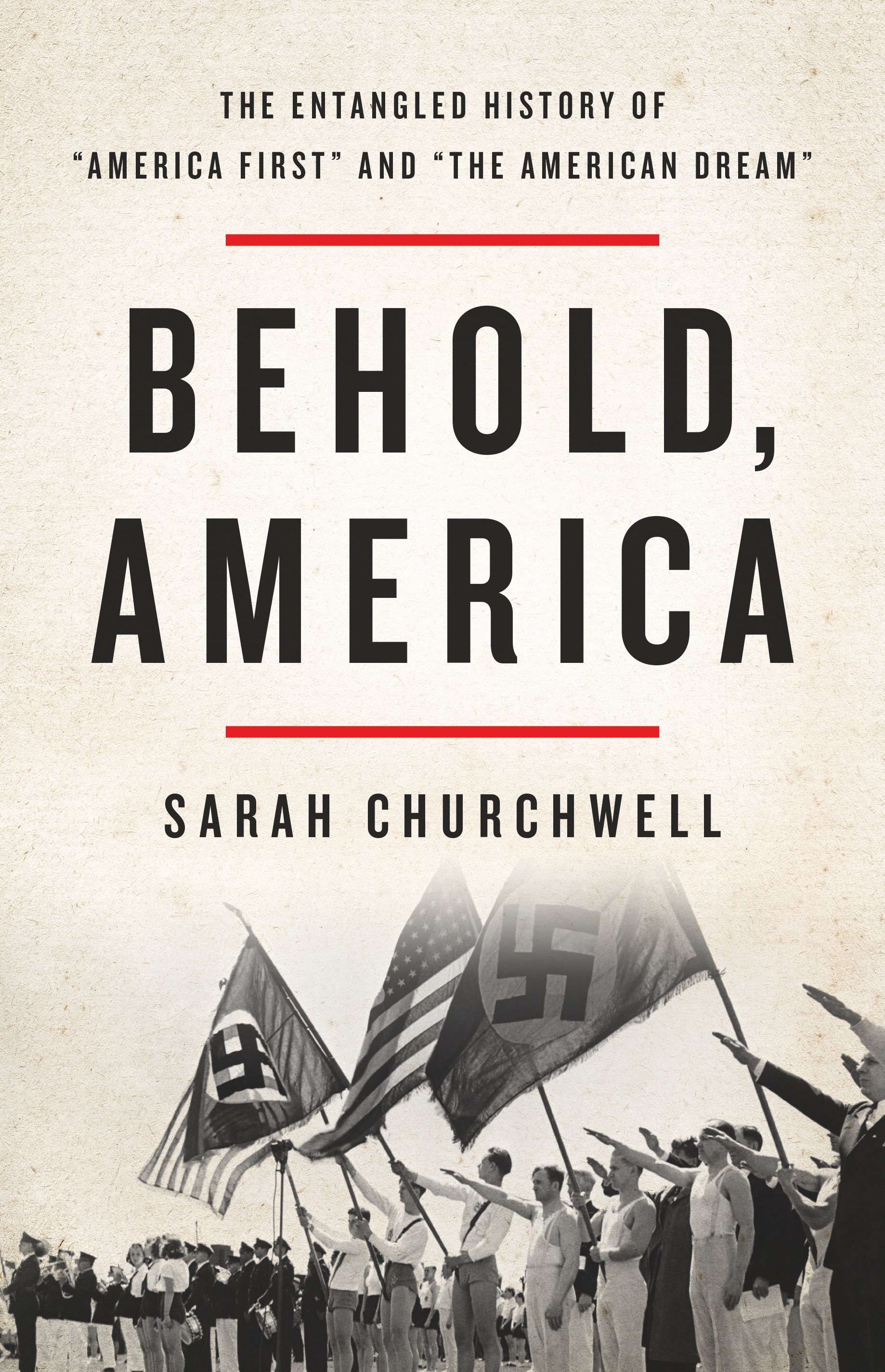

How did these two phrases come to mean what they do today? And, more to the point, what do they have to do with each other? In her latest book, Behold, America: The Entangled History of “America First” and “the American Dream,” Sarah Churchwell unearths the origins of these loaded phrases, which over the course of more than a century have become flattened into the planks of America’s mythology of enterprise—and thereby of its hegemony.

Churchwell, a professor of American literature and public understanding of the humanities at the University of London’s School of Advanced Study, recently spoke with Pacific Standard about this overlooked history—and about how confronting the afterlives of these phrases can show us how America can make good on the original promise of the American dream.

One thing that makes your book stand out is its sharp sensitivity to words. What drew you to this particular project?

I was particularly struck by the fact that these phrases that are so powerful right now are also so hugely under-examined. And since I’m trained as an academic literary critic, I thought that the techniques of close reading, textual analysis, and, in this case, tracing genealogy and historical sensibility could really open up the meanings of words that are currently shaping our political discourse, and in ways that people are often largely unconscious of. In particular, when you’ve got phrases that can be used in different ways by different constituencies—phrases that can be manipulated and used in disingenuous ways, what’s usually referred to as dog whistles—well, it seems to me that those distinctions are exactly the kinds that a literary critic is sensitive to.

So I started digging into the history of these phrases, to try to see what I could find about shifting meanings, about how old these ideas really are. I especially wanted to know if our assumptions about their meanings are accurate. And, unsurprisingly, they’re not at all. The more I dug, the more I found myself thinking that this is really a way to tell a history of the first half of the American 20th century and the ongoing arguments over the meaning of America.

(Photo: Basic Books)

Let’s tackle that history. What’s the lineage of “America first”? And why is it important that we know it?

I’d been studying the American ’20s for a long time for a book I wrote about F. Scott Fitzgerald and the milieu of The Great Gatsby. So before Trump had started resuscitating the phrase, I knew from that research that “America first” was this incredibly prominent and politically influential phrase in that decade. But it didn’t really register with me at first because it didn’t have any relevance. It was just a discarded and discredited political slogan. And then all of a sudden Trump revived it. People started talking about Charles Lindbergh and about how the phrase had emerged with him. I knew that wasn’t right. And I thought back to my research and how that phrase was deeply associated with earlier notions of isolationism—like in debates over whether America should join the League of Nations—and with anti-Semitism as we think about it in the Lindbergh context. But, crucially, it was profoundly white nationalist, and absolutely connected with the early rise of the second Ku Klux Klan in the late teens and early ’20s.

The phrase hugely shaped the domestic and foreign policy ideas of America for almost the first two-thirds of the 20th century. And so to see “America first” solely as this one phrase that one anti-Semitic pilot used in the argument about whether the country should enter World War II is just way too reductive and oversimplified. So that context from the ’20s is, to me, more pertinent than the Lindbergh context, but Lindbergh was all anybody talked about. It’s crucial that people using “America first,” who think that it’s just patriotic, are aware of the fact that it has a very dark history. I hope that at least some of them might reconsider their support of it, and their idea and their argument that it’s an innocent phrase, because the history is anything but innocent.

And what about “the American dream”? We essentially think of it in terms of the bootstrap myth—that anything is possible as long as you work hard enough. But that’s not what the phrase initially meant.

This also came out of my research on The Great Gatsby (1925), because The Great Gatsby is known as the great novel of the American dream and yet it doesn’t use that phrase, and the phrase wasn’t popularized until 1931. So I was really surprised to learn that it was a phrase that was first used in a consistent way to describe a national value system on the left, not on the right. Today, it kind of cuts across the political spectrum, but when it’s used on the right, it tends to be, as you said, an argument for a libertarian notion of radical free-market capitalism, of individual success. You’ll hear right-wing pundits say that the American dream is antithetical to any kind of welfare state, to any kind of social democratic impulse. But it turns out that the phrase was coined to argue for exactly those kinds of social safety nets, and to argue against the privatization of wealth.

The earliest instances that I found of “the American Dream” used to describe that kind of national ideal were in 1895, 1900. So this is Gilded Age monopoly capitalism. We’re talking about the era of Rockefeller and Carnegie and Mellon and Frick and Morgan—this consolidation of private wealth. There was also this new thing called a multimillionaire that America had never seen before. And people on the left said that if this multimillionaire is allowed to take hold of American society, it will mean the death of the American dream. One newspaper called it an un-American dream, because the American dream is of egalitarianism. It’s of equality, of opportunity for all, not just for the privileged few.

And they saw very quickly that if you allow that kind of private wealth to consolidate and establish itself, you’re going to replicate an aristocracy, which is exactly what the American government was designed to resist. People weren’t naive. They knew that that kind of wealth could become an oligarchy, that it could become a plutocracy, that it could control government interests. And they said that it’s an un-American dream to want this wealth, because the American dream is supposed to be about collective well-being, not individual status.

But then the debate became: Where does individual well-being, individual prosperity, individual ambition end, and where does collective well-being, collective ambition, a notion of what a good society looks like begin? And that’s really it. Now, though, we tend to see only half the story.

How did these two phrases eventually bang up against each other?

Initially, I thought that they were running in parallel lines—that there were these two different ways of looking at America, different arguments that map onto current ideas about progressivism versus conservatism, about tolerance, inclusiveness, pluralism. But in fact they were converging lines—where they tangled directly was over that debate about whether America should enter World War II. And Lindbergh’s “America first”-ism was very much in direct open debate with more inclusive, progressive, older ideas of the American dream, before the phrase was taken over by ideas of American individual success. People said that this “America first” notion that Lindbergh was popularizing—this idea that America isn’t responsible for what’s happening in Europe, that America could just go it alone and be purely isolationist—wasn’t only unrealistic, but also against the American dream of inclusivity, tolerance, and democracy.

What’s interesting is that that moment—that debate about whether we should enter World War II, which was won on the basis that the American dream meant that we should go and fight on behalf of democracy in Europe—was actually part of what helped to flip the meaning of the American dream, because the meaning switched after World War II, as part of the Cold War, as it became associated with this kind of American triumphalism. It became associated with this idea that we had won the war and had won the ideological battle, and that it was how we were going to defeat the Soviets, too, because American capitalist democracy was clearly the best way forward.

Bringing this back to the present, have you noticed, since you first set out to write the book and since it was published, whether these phrases have been changing, even in small ways?

The current meaning of “the American dream” is so well established, and so thoroughly embedded not just in America but around the world, that I don’t see much evidence that people are seeking to change the conversation in that way. That said, what I think is interesting is that in the debate about collective well-being and about a social safety net and about the welfare state—we keep hearing that the left has nothing to say except that it’s anti-Trump. And I think that’s profoundly inaccurate. Those older debates were talked about in terms of the American dream, so to me it’s incredibly empowering—as an individual citizen, not just as a literary historian—to make those arguments and say, Hey, you know what, this was the American dream, literally and originally the American dream. It gives a very powerful rebuttal against people who want to say that radical free-market capitalism is the only American way. You can make an argument that we’re reclaiming the American dream.

I’ve started to see the meaning of “America first” shift somewhat even since I started researching for the book, because more and more people are contributing to the discrediting of the phrase. And my book is just one of many efforts to issue a warning to people who are trying to use it innocently—to say that this is a dog whistle. This is about white nationalism. Stop pretending that there isn’t a white supremacist history to this, that there isn’t a white supremacist subtext. I think that we’re seeing a mounting resistance not just to the Trump administration and to his presidency, but to that phrase in particular—to its pernicious meaning.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Pacific Standard’s Ideas section is your destination for idea-driven features, voracious culture coverage, sharp opinion, and enlightening conversation. Help us shape our ongoing coverage by responding to a short reader survey.