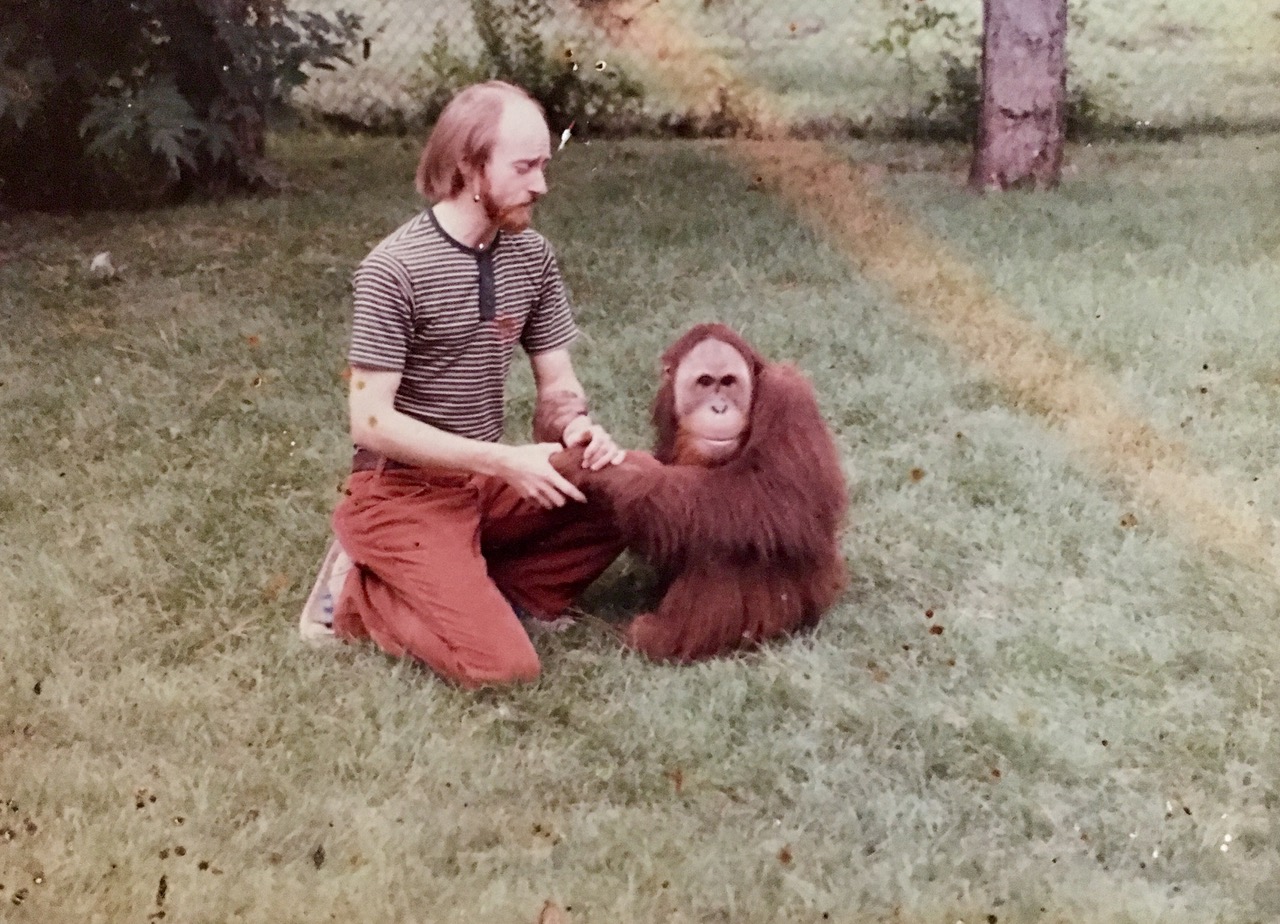

(Photo: Courtesy of Carson Vaughan)

In May of 1983, Dick Haskin graduated with his bachelor’s degree, moved to a small flat in an old two-story house in the shadow of the Nebraska Capitol Building, and set about finding a job working with non-human primates, a task that proved exceedingly difficult for a newly minted college graduate without any firsthand experience. Nor did it help that Dick hated zoos, considered them morally perverse. He sent inquiry letters to nearly every primate facility in the country, from the Gorilla Fund to the Oregon National Primate Research Center to the Primate Foundation of Arizona and several more abroad, anywhere that might provide a gateway to Africa. He wrote to the Karisoke Research Center in Rwanda, founded by primatologist Dian Fossey, and to Jane Goodall’s Gombe Stream Research Centre in Tanzania.

Most facilities ignored the letters completely. A few sent applications, only to reject him shortly thereafter. But when the Yerkes National Primate Research Center in Atlanta invited him to its facility at Emory University for an interview, he went all in. He broke his lease, packed everything he owned into his 1968 Ford Galaxie, and hit the road. He took the scenic route, took his time, south to Oklahoma, east to Arkansas. He even toured the ranch of his country idol, Loretta Lynn, in Hurricane Mills, Tennessee. But when he finally made it to Emory University, the interview lasted just minutes.

“They just came out and told me there was no chance of getting a job working with primates because I had no experience,” he says. “My dreams were dashed.”

When he left Georgia, he’d resigned himself, at just 23 years old, to washing dishes for the rest of his life. He felt “utterly destroyed.” He returned to the cafeteria in Lincoln, head hung low, and asked for his old job back. And while he was at it, he asked the food services director, half-jokingly, almost involuntarily, if he knew anyone who worked at the zoo in Lincoln, as if his dream, like a tom turkey minutes after the blast, were still flapping its wings in the dirt.

(Photo: Little A Books)

“I’m a friend of the director. Why?”

“Maybe I can work with their primates,” Dick suggested.

He hated zoos—truly, viscerally hated them. Hated the guilt he felt just looking between the bars. But without more experience, his dreams were dead in the water, and more than anything he wanted to feel alive, wanted to feel that primal rush of freedom that he’d first felt as he watched Jane Goodall projected on the wall of his eighth-grade classroom. He wanted to fight for the apes. Study them. Save them. He was desperate.

When Dick arrived for his interview the next morning, it was only the second time in his life he’d stepped foot inside a zoo. He was just seven years old the first time, visiting his sister Bonnie in Lincoln with his parents. They toured the city’s Ager Zoo on a warm spring afternoon, the crab apple trees flowering pink and white in the sun, a den of vines slithering up the old limestone WPA building. Tourists crowded the walkways and clumsily organized for family portraits. Dick marveled at the animals inside—at the birds and the monkeys and the alligators—unlike anything he’d ever encountered on the farm, especially the chimpanzee. Dick leaned forward on the gate, standing on his tippy toes, craning his neck toward the animal. But the longer he stared, the worse he began to feel. The chimp lurched around his cage, shook the bars, threw fistfuls of straw at gawkers like himself. The chimps he’d seen on television, in picture books—they seemed buoyed by their human counterparts, not oppressed and certainly not indentured. He felt heartsick, and then he felt angry, and for the first time, he seemed to understand what freedom was and, more importantly, was not.

“He appeared miserable. I hated it. I thought it was so cruel,” Dick says. “That experience has remained with me my whole life.”

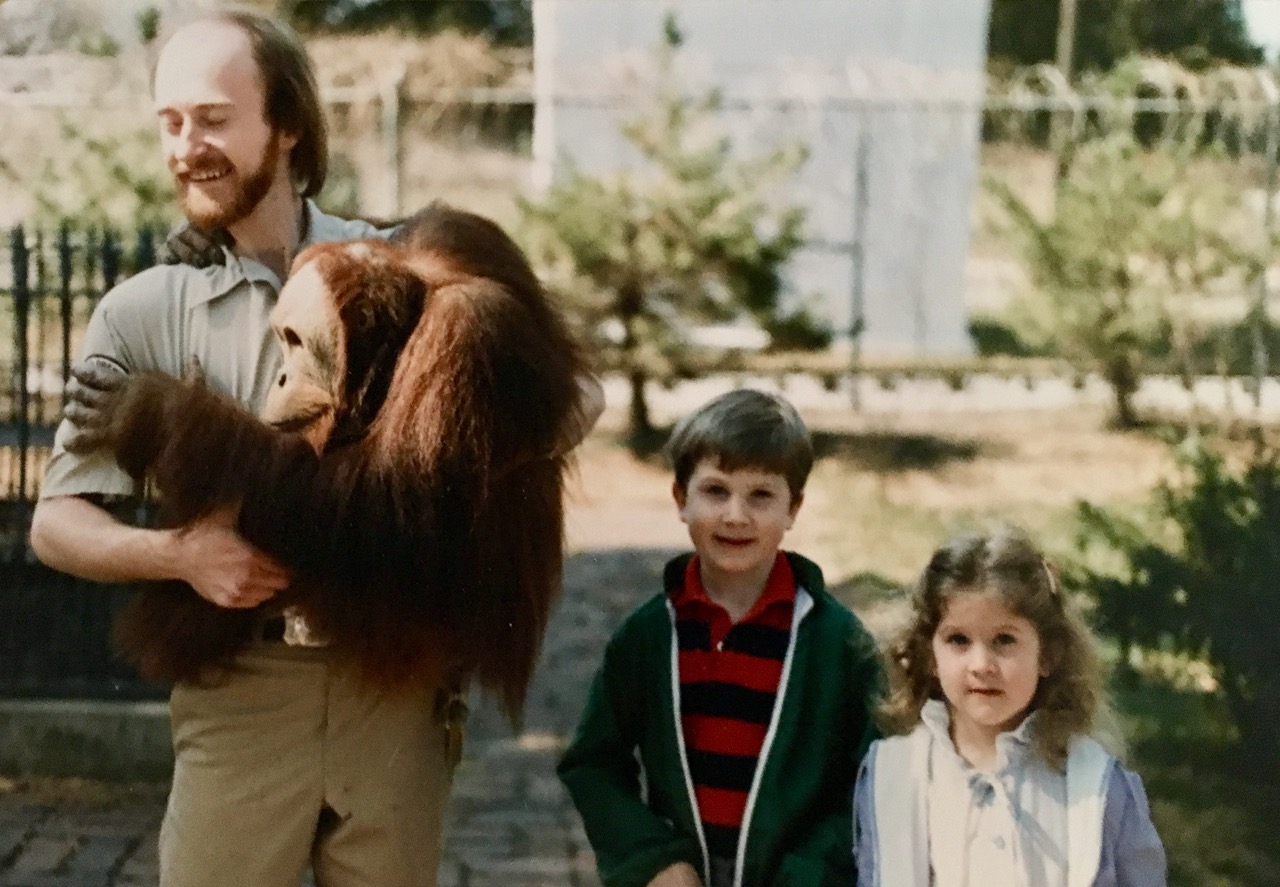

(Photo: Courtesy of Carson Vaughan)

At the time, neither Dick nor his parents had any idea there was another zoo, this one privately funded, just out of eyeshot farther down the street, a zoo that would quickly outshine Ager in both size and reputation: the Folsom Children’s Zoo. By the time Dick arrived for his interview in the summer of 1984, Folsom had developed a reputation as one of the premier children’s zoos in the country, boasting 65 species—from petting goats to a 1,600-pound Kodiak bear named Gentle Ben, who had starred in the Grizzly Adams television show.

Despite the Children’s Zoo’s prestige, Dick couldn’t staunch the feelings of anger and sadness cropping up as he passed through the gates, past the tulip beds and the railroad tracks and the small stream meandering through the park. He’d spent the better part of his childhood among wildlife, at the farm, at Grove Lake, in the hills north of Royal, and he’d seen what freedom looks like: a herd of whitetail deer bounding effortlessly across a barbed-wired fence; a bobcat slinking through a grassy meadow; a fox trotting along the banks of the Verdigris; a family of raccoons crossing the road, one by one, under the cover of night.

Everything for Africa, he told himself. Just another stepping stone. Despite Dick’s hesitations, Al Bietz, a self-declared “animal egghead” with a thick salt-and-pepper beard, a booming voice, and a pearly white smile, liked him immediately. Like Dick, he was a kindhearted man who understood what it meant to be wholly consumed by another species. The board of the Folsom Zoological Society had appointed Bietz director of the Children’s Zoo in 1973, and in the decade and change since then, he’d developed something of a sixth sense for identifying fellow eggheads.

(Photo: Mary Anne Andrei)

“He didn’t come in like so many people do and say, I want to work in a zoo because I love animals. That almost disqualified anybody that came in,” Bietz says. “He impressed me as somebody who was just consumed, almost obsessed with the subject. He had a dream and a goal, and that was to work with great apes.”

Even then, Bietz wasn’t about to let Dick step into the chimp enclosure on day one.

“They’ll kill you,” Bietz said. “But I tell you what: We’ve got a snow monkey that was raised as a pet that we’re trying to integrate into the group. I’ll hire you to work on that.”

The Super 8 had recently offered him the title of assistant manager, a position with upward mobility and an honorable income. When Dick chose the meager-paying zoo job instead, his father’s temper returned, a stark reminder of why he’d been so eager to leave home in the first place. But with more miles between them now, the pressure was easier to brush off. Dick worked with Skokie and the other snow monkeys until the current chimp handler left the zoo a few months later, and Monica, the pinch hitter—like a bad transplant—never quite took. So Bietz, who’d spent many long hours discussing primate behavior with Dick, letting him regurgitate everything he’d learned through his compulsive self-directed studies, asked him to shadow Monica. A few days later, Dick delivered his final diagnosis as if he’d been studying apes his entire life.

“She’s scared of them,” he told Bietz. “Everything she’s doing is causing problems. The way she’s moving—she’s scared of them, and they know she’s scared of them. You’ve got to get her out.”

Dick had studied Monica’s posture, her gestures, the way she flinched and blinked, and the way the chimps responded, taking advantage of her hesitation. Bietz took notes, and though he didn’t necessarily disagree, he wasn’t ready to remove her either. One week later, Bietz approached Dick again. Monica had been attacked the night before. She was currently in the hospital, bruises all over, stitches but no broken bones.

“You’re going in,” Bietz said.

Excerpted from Zoo Nebraska: The Dismantling of an American Dream by Carson Vaughan. © 2019 Published by Little A, April 1st, 2019. All Rights Reserved.

Pacific Standard’s Ideas section is your destination for idea-driven features, voracious culture coverage, sharp opinion, and enlightening conversation. Help us shape our ongoing coverage by responding to a short reader survey.