Jia Tolentino is a genius. I know “genius” is an overused descriptor, especially when trotted out by non-geniuses such as I, whose opinions maybe don’t count as much as those from people who actually finished their courses at community college—or, for Tolentino, at the University of Virginia—but in her case it is totally warranted. I’ve been reading her work from the jump, since the days of breathlessly waiting for her byline to pop up on Jezebel or The Hairpin because I knew whatever she’d written was going to be dope.

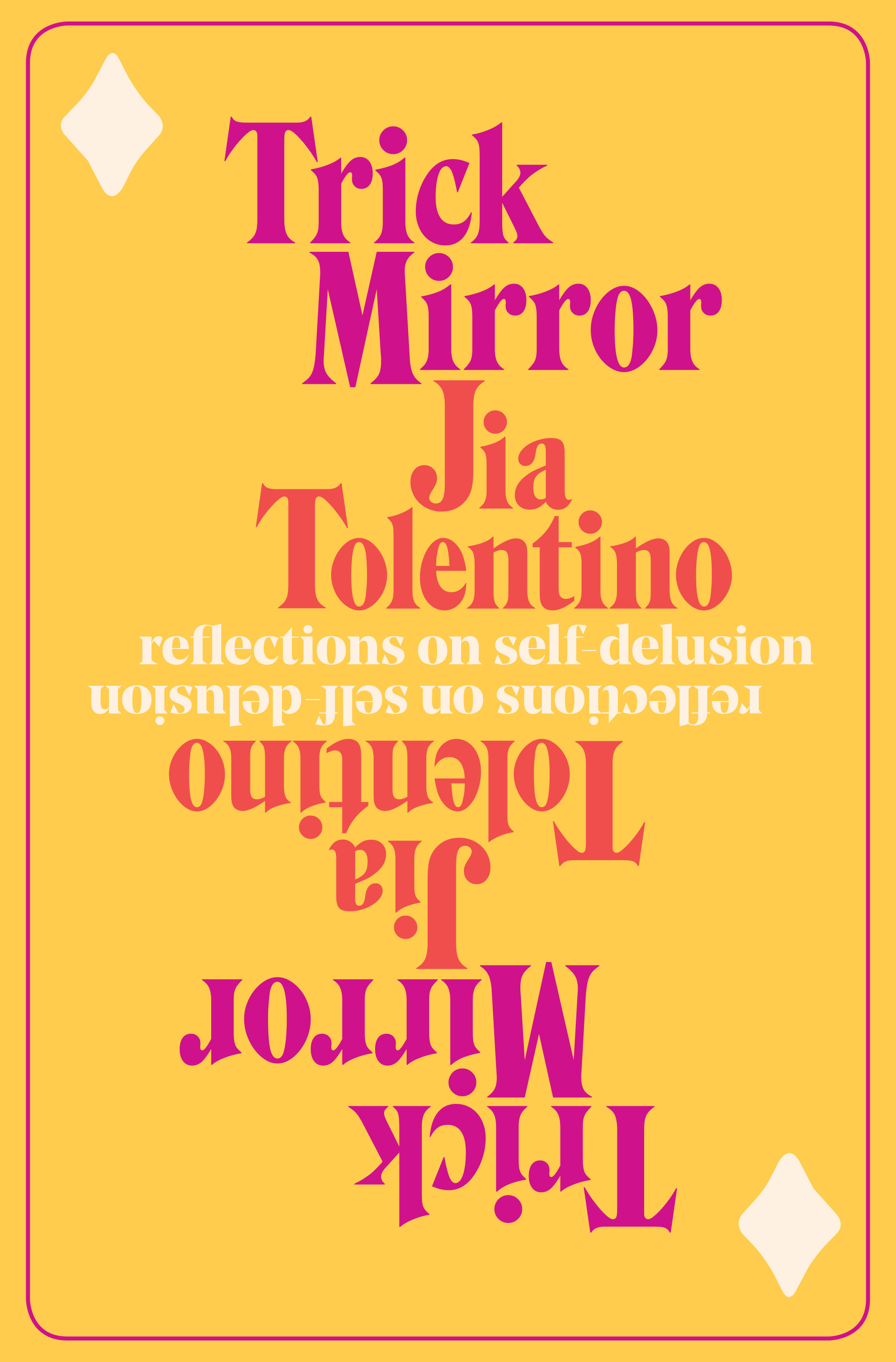

In her new book, Trick Mirror: Reflections on Self-Delusion, The New Yorker staff writer offers us a collection of nine longform essays covering culture, technology, and politics. These pieces are smart and deeply unsettling but also funny—the best trifecta one could ask for. I am in awe of the skill with which she dissects a subject and then puts it back together in a way we’d never seen it before. Pacific Standard sent me to fangirl over Tolentino, to ask her my burning questions about her writing and editing processes, and to ponder why scams and scammers are so damn captivating.

Here’s why I wrote my first book: I used to read at live storytelling shows around Chicago, plus I have this blog that a lot of people used to read, and these dudes who ran an indie press kept hounding me until I agreed to write a book, which I finally did because the contract (which they wrote on a used piece of toilet paper) basically said “YOU CAN WRITE WHATEVER YOU WANT.” How could I pass that up? Then I wrote the other books to pay the taxes on the books I’d written before.

OK, your turn. Did you feel compelled to write your debut collection? Was the book an easy thing to knock out in your free time? Did someone from Random House thrust a comically oversized cardboard check into your hands that you felt guilty refusing?

I hope that every contract you get for the rest of your life is just “YOU CAN WRITE WHATEVER YOU WANT” printed on increasingly deluxe material. Next time I hope it’s that, embossed on huge stacks of gold bars.

I did always want to write a book in some vague way; books have always made up such a major part of my world, and I’ve known since at least college that writing was the thing I liked doing most and the only thing I was good at. I wanted the experience of putting a lot of sustained, intense effort into something and seeing what came out. I finished a novel during and after grad school, actually—I worked on it for four years and then shelved it, and have never regretted either spending so much time on it or relegating it to non-existence, because the process of writing it taught me so much. I also spent a lot of time in the Peace Corps, until someone stole my laptop out of my backpack at an Internet cafe, working on the first hundred pages of another novel; the story was going to be set on one summer day with four female friends, with flashbacks to their first year after college. And, literally, my working title was GIRLS.

[Trick Mirror] came out of the sudden sense, post-election, that I wanted to devote myself to something, that I needed to try to sit with this sense of existential uncertainty that was saturating me. I knew that nothing was going to make sense and everything was going to feel bad for a while, and that writing a book was one way to take feelings of ambient puzzlement and agony and turn them into something concrete and possibly useful.

How do you decide what you want to write about? Do you just cover what interests you, or do you see what other people are talking about and decide to do it better than they can? Or do you see a hole and decide to fill it?

I write about anything that grabs me enough that I’d subject a friend to a conversation about it in real life, if that makes sense. And luckily my editor is down for me to write about things as disparate as abortion law and Millennials on Twitter begging Cate Blanchett to step on their throat. It’s really nice, in general, to be able to follow a rubric of personal chemistry and not one of objective importance. Like, I don’t think there’s any way I’d ever be able to do the job of a national opinion columnist and have to constantly be writing on whatever the highest number of people would identify as the biggest issue of the day. I have a hard time doing anything out of a sense of obligation—my life tactic is to semi-consciously try to shape my desires so that they’ll work in my favor—and I think my writing gets very flat very quickly if I feel an external pressure to “weigh in.” The internal pressure to write something hard or fun or refreshing is much better.

I am, though, sometimes motivated by the sense that a topic is everywhere but that something is missing. I think I write a lot about things that are very obvious but under-articulated—I almost never have had the sense that I’m saying anything new.

(Photo: Random House)

Is your book-writing process the same as your article-writing process? Sometimes book deadlines feel like you have months to toil away at this dumb thing while getting zero feedback. Did you make a schedule? Did you set aside a block of time for research, then start writing after you compiled everything? Did you wing it?

OOH BABY, this is the question I am always curious about. I am absolutely nowhere near talented enough to bang out a book that quickly. It’s interesting: Your writing is so animated by this sense of sudden, kinetic, explosive momentum, and I wonder if the tones we take or strive for are always related to the rhythms of the way we work. Which means that whatever way we gravitate toward working is probably the single way we have to work to get anything done.

I tend to be pretty regimented with magazine stuff. One of the things that I rely on most, in general but especially with writing, is having developed a reliably correct instinct for how much trouble things are going to be, and as soon as I get an assignment, I start blocking out a rough schedule to get it done in good time. I like to do a lot of work early so that I can let my life interfere and sidetrack me, and then still hopefully be able to finish a project without that last-minute panic, which is completely paralyzing for me. Again, I think I function a lot better with internal pressure than external pressure.

With the book, the first thing I did after getting the contract was figure out that if I was going to turn the book in on time, I needed to finish a rough draft of an essay every month and a half, and then I would get a few months just for editing. I also immediately understood that I would need outside help to do this. My friend Carrie Frye, formerly of the Awl, is an unbelievably brilliant and kind editor who has a freelance book editing service called Black Cardigan. She essentially gave me a schedule of me filing drafts and her giving me feedback, and we just went essay by essay until the whole thing was done. (This seems very orderly, but in my brain it felt like running for the bus with a backpack on for 18 months.)

I wrote the whole book in Scrivener to help me keep track of the research, which is always my favorite stage of writing, maybe because it is easy (and fun?) to do while you are lazy or stoned or hungover. With the six weeks of every essay-drafting block—and as I write it down now it is clear to me that that is not enough time—I spent the first two or three weeks just reading and reading whatever I could.

What has been the scariest or worst part of the book writing process for you? I will admit that the worst part for me is copy editing, because these faceless grammar police are very good at their jobs and they will look up even the tiniest reference and leave a note in the margin like, “Hey Sam, this wasn’t invented in 1998, are you sure you want to leave this inaccurate joke in?” and I want to go, “YES I DO THAT IS THE POINT OF THE JOKE.” But you can’t say that.

Has there been a part of this where you were just like, “I hate this, this sucks?”

I masochistically LOVE being checked and corrected (and better by a professional than by the person on Twitter that will inevitably tweet my errors at me!), so copy edits weren’t so bad, in part because I’d also hired a fact-checker to help me get rid of a lot of that stuff beforehand. I did 100 percent have that “I hate this, this sucks” feeling when I was going through the U.K. legal edit; they’ve got such a high standard for what could be considered defamatory that I had to, like, solicit a written message from my boyfriend saying that I wasn’t invading his privacy with the weddings essay, and had to argue down additions that would (for example) clarify, if I mentioned Harvey Weinstein even in passing, that he denies all the allegations and that he has not legally been found guilty of a crime. I was like, Harvey Weinstein is not going to sue me, and if he does, that would be incredible publicity, so chill.

But otherwise, the scariest part of the book-writing process was the period immediately following the book deal. Getting this advance from Random House was fundamentally life-changing; the last two years are the first of my life where I have been able to trust not just that I would be OK in the event of a financial emergency, but that I would be able to help people in my family in the event of one of their own. And so right after I accepted it, I felt this deep, nauseating horror that I would fuck up the money somehow. It was so clear to me that there was a real possibility that I’d write something that wouldn’t live up to their expectations, and also a real possibility that I’d just write a book that sucked. And then I wrote down all the worst things I thought the book could be—annoying, tedious, blinkered, obviously self-delusional, etc.—and looked at them and was like, whatever man, you are so lucky to have gotten into a situation in which the worst thing that happens is that you write an annoying book.

Are you looking forward to book tour? What are you going to pack? (I did a two-month book tour, and my secret for surviving was disposable underwear.) Do you know which passage you’re going to read yet?

I recently realized that I hadn’t ever imagined this part of a book coming out. So I haven’t really thought about what book tour is going to be like, even still. (HELP?!?!) But actually, I never really think about what anything’s going to be like, and luckily I’m not going to too many places: I have something like eight stops over the course of a month, and then just a few random things throughout the fall.

I will say that I’m a great packer. I always have portable speakers, matching pajamas, weed gummies, and books. And maybe I’ll read this passage that people keep tweeting at me, which I just tried to find on Google Books as such until I remembered that I have the whole book on my computer. Anyway, it’s a passage about why the Internet is bad.

Girl, I love a scam. I grew up poor, and when you’re poor it feels like life itself is a goddamn scam, and I don’t laugh when someone gets scammed but I often feel … relieved? Like, “OK, wow, you’re gullible, too!” But also, the sheer nerve it takes for a bitch to boldly scam people without seeming to give a shit about the repercussions is straight-up exhilarating to me. Imagine being that ballsy! I’m terrified of my card getting declined at the pharmacy, so reading about people who absolutely don’t care about wasting millions of dollars makes my heart race in the bad way—but I can’t turn away. If you could get away with a scam, what would it be?

Life IS a goddamn scam when you’re poor! It drives me nuts that so many people don’t understand (or aren’t willing to really consider as relevant to their existence) the fact that it is so fucking expensive to be poor: that you’re constantly penalized by the same infrastructure and banking system and basic cultural mores that exist to make wealthy people as comfortable as they can be! I grew up middle-class but unstable enough to understand this intimately to some degree, and though I am grateful that educational institutions have largessed me into upward mobility, it is continually wild to me to encounter the depth of the belief, among wealthy people—or maybe I should say the mostly uncaring knowledge—that the world exists primarily to give them what they want.

I’m fascinated by high-end scams for that specific reason you’re talking about too. It’s that voyeuristic amazement at a world in which anyone who went to private school can be out here scamming enormous amounts of money out of people under the aegis of entrepreneurship, when, at the same time, there are untold numbers of busboys and warehouse workers in this country who’ll get fired if they show up seven minutes late. And despite thinking constantly about the way power can remove the need for accountability, it can still shock me, as in the case of Jill Abramson’s book. It does give you an electric jolt, thinking about what it’d be like to live in the world with that kind of unshakable confidence in your own position. And, when the people being scammed are also probably scammers, like the people who bought those wack-ass $700 juicers from Juicero, it’s a good time all around. If I could get away with a scam, I’d want it to be something like that, or I’d want to bait Betsy DeVos into investing in some nightmare start-up (charter schools that are just work camps for low-income children) and then steal all her money and go live on an island without an extradition treaty for the rest of my life.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Pacific Standard’s Ideas section is your destination for idea-driven features, voracious culture coverage, sharp opinion, and enlightening conversation. Help us shape our ongoing coverage by responding to a short reader survey.