Growing up in a multiethnic suburb outside Los Angeles, Malaka Gharib was confused. She saw white people everywhere: on magazine covers, on the television, in movies. They seemed confident, rich, fashionable, and good looking. They had small nuclear families, big homes, and cool jobs as magazine editors. They definitely didn’t seem to live with large, extended immigrant families; have dark, coarse hair; or eat Spam, as Gharib had done.

As a teenager, the daughter of a Filipino Catholic mother and an Egyptian Muslim father, Gharib struggled to understand and accept her own fascination with pre-Internet, white-dominated pop culture while her high-school peers, almost all kids of color, called her a poser and excluded her from their neat ethnic social groups.

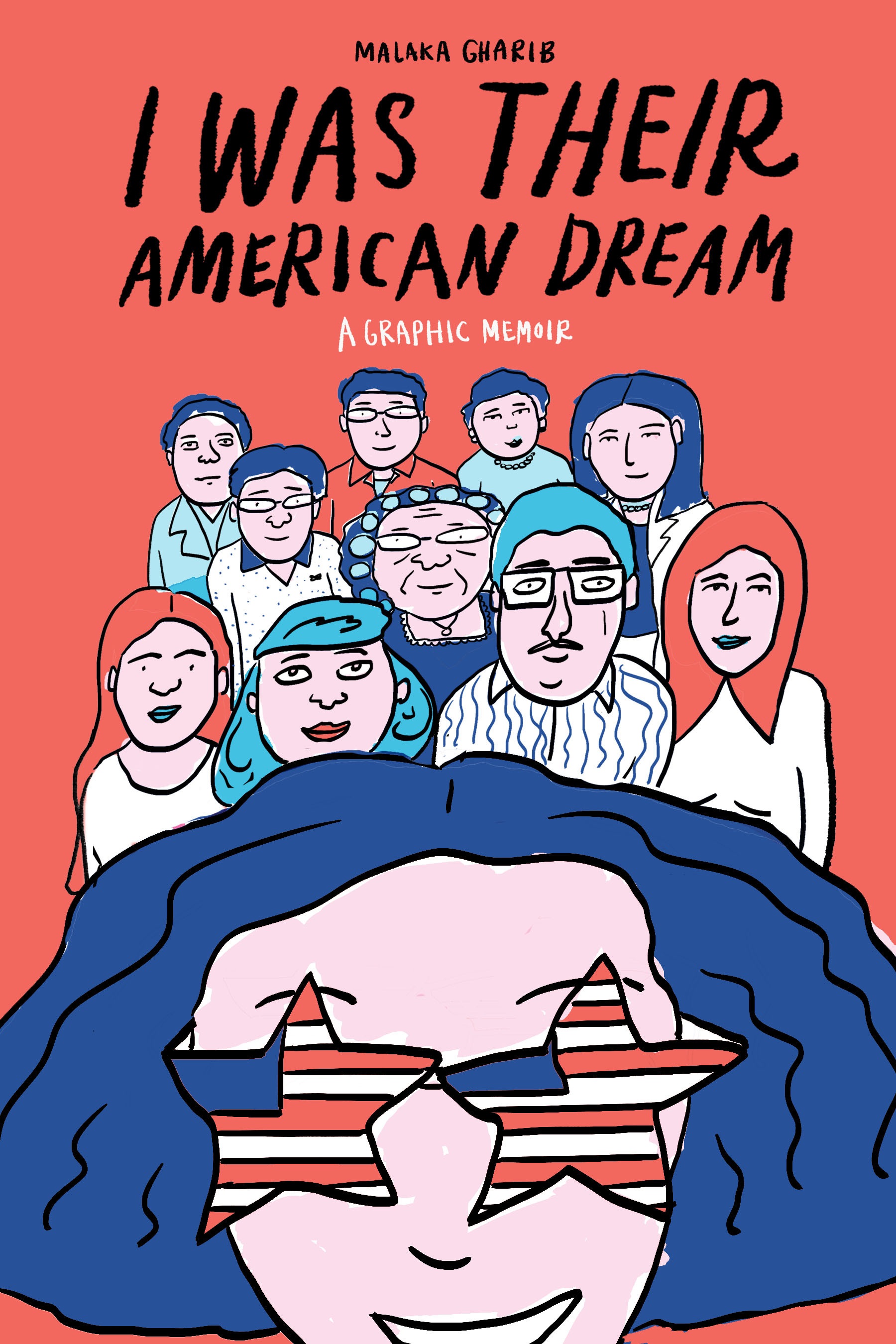

Now a journalist at NPR, Gharib traces her coming-of-age story in the graphic memoir I Was Their American Dream. Her debut book uses a charming and playful graphic style—reminiscent of punk scrapbooks, screenprinting, and ‘zines—to recount a first-generation American upbringing. Opening with Gharib as a pre-teen, the book traverses Gharib’s parents’ divorce and failure to achieve their American dream, her early code-switching depending on whether she was in the United States or Egypt, her sense of alienation at school and work, and her eventual self-acceptance in the present day. Gharib’s parents—prominent characters throughout the book—voice their expectations and hopes, while Gharib learns to embrace her misfit self and her hyphenated Filipino-Egyptian identity. I Was Their American Dream gleefully tackles the nuance of the question “What are you,” discusses what it’s like to be the only family member married to a white person, and offers advice for accepting the weirdo you’ve always been.

Gharib spoke with Pacific Standard about her first book, the pressure she faced to make up for her parents’ unfulfilled dreams, and how she brushed off the taunting she got in school for acting “whitewashed.”

Can you explain the significance of the book’s title?

It’s really literal. My parents worked so hard and never got a big break in their lives. They made a lot of tough choices in raising me. I feel like they had so much hope for themselves and for me when they first came to this country, so I felt pressure to make up for what they had sacrificed. They didn’t have their American dream, so I had to make up for it. Otherwise it wasn’t worth it.

The book opens with your mom telling you: “You have to be better than us,” and over the course of the book, it becomes clear that her vision involves you securing one of only a few “acceptable” jobs. These days, you write, draw, edit, and make ‘zines—jobs that didn’t make your mom’s list. Have you succeeded in your parents’ eyes?

(Photo: Clarkson Potter)

My dad will always tell me: “Why aren’t you with your family? Why are you all the way out in D.C.?” The dutiful thing as a Filipino American would be to live close to my family, so there are just a lot of norms you have to break in order to be your own self. My choice of being a writer, an artist—they’d be much happier if I’d worked in nursing. But in the end, they say that they’re proud of me, which is good, even though I know I don’t fit the conventional mold of success in their eyes.

Also I had to go remarkably, remarkably far in being a writer and artist in order for them to appreciate it and call it success. I work at NPR, and I wrote a book, so I went the farthest I could have gone with that.

Your relationship to being asked “what are you,” when someone is trying to figure out your race or ethnicity, changes over the course of the book. How do you think about the question now?

Culture and ethnicity were so important to me as a young person—not acknowledging what your ethnicity is erases a part of you. I know the question can be really reductive, especially if it’s a non-person of color asking the question, but I actually found that in college, when white people didn’t ask me the question, I really missed it. [The question] gave me a chance to talk about who I was. It was often the only entry point to talk about race.

In the new Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse movie, for example, it was very important to know that the child main character was half-Latino and half-black. This representation matters more than ever, and to be able to proudly say who you are helps create cultural fluency and awareness. Maybe a person doesn’t know what the daughter of a Muslim immigrant and an Asian Catholic looks like—and here I am! So these days, I happily disclose who I am when someone asks. Most times, people mean well.

Much of the book takes place during a time when you felt alienated—from your parents, classmates, and other Filipinos. You describe yourself as a “minority among minorities.” Do you still feel this sense of alienation?

I sometimes have to over-prove that I’m Asian, or with Arabic people I always trip up because I know my Arabic is shitty. Even now, I feel a sense of insecurity about the cultures that I represent because I don’t look either way.

I still try to surround myself with people from my culture, like how I have this Filipino food club at NPR. Even if I don’t look like my Filipino colleagues, I can eat the food, and it feels like home to me.

The first time we had a potluck, I was thinking, “Wow, it’s so nice to be Filipino at work!” For so many years, I hid any part of my brown self in predominantly white work spaces. I think [the potluck] was a relief for all of us. That club has actually been a really instrumental part of making me feel more comfortable in my skin over the past couple of years.

(Photo: Ben de la Cruz)

I feel like food is the unspoken protagonist of your book.

I actually try not to lean so heavily on food as a shortcut for culture, because culture manifests itself in so many ways. Other than food, how do I know I’m Filipino and Egyptian? Other than traditions and songs, how do I see my culture in myself? A lot of it ended up being about values, like attitudes about family, sharing, familial obligation, familial piety, and hard work. I find that’s often unappreciated.

How did your upbringing and the values that came with it prepare you for a predominantly white working world?

I was just thinking about this because of a viral thread from this cultural critic named Muqing M. Zhang. Basically this woman had written an article saying, “I don’t hire anyone who doesn’t send a thank you note after an interview.” And Muqing, who is Chinese, basically said: “This is exactly the problem. You hold us up to these social norms, but we don’t get this kind of training from our family or peers. We’re always second-guessing what social cues we have to do and what’s acceptable in the workforce.”

[When I read that thread,] I felt like, “Yes, oh my gosh, yes!” I didn’t learn anything about thank you cards. I had to learn that from watching my classmates in college after internship interviews.

The book has a few one- or two-page scenes with a much finer level of detail in the illustration, such as a close-up of your face or someone else’s. These are often quite touching. Was the idea behind these panels to effect a set of narrative pauses?

I wanted people to really see me. It was very important at the end of the book to draw my parents as real as possible, to remind readers that these are real people, not just this cartoon world with people rolling around in rice.

Anti-immigrant rhetoric is what pushed me to write the book in the first place. When I’d look at the news, I felt like it wasn’t an accurate depiction of my life as a first-generation American. People not only don’t like [immigrants and first-generation Americans], they don’t get us, and they don’t have our stories right! That’s why I started drawing these little illustrations about my parents and the things I like about being brown. That turned into the book.

(Photo: Clarkson Potter)

One of the first cartoons I did was my of dad, the Muslim that America fears: He wears denim shorts, likes fried chicken, and loves Tom Hanks. It was just a very different picture. I also wanted to encourage other people of color to share their own stories and also see their stories in mine.

Is the book your way to push against those misguided depictions?

This is a book I wish I had growing up. I was obsessed with American Girl dolls, but I just didn’t see my story reflected in them. I grew up trying to emulate people that I thought I had to emulate. I wish someone had just told me, “Your story is so normal, and here’s a book about it!” Maybe I would have learned everything I learned as an adult so much earlier. Maybe I would have been a different, more comfortable version of me.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Pacific Standard’s Ideas section is your destination for idea-driven features, voracious culture coverage, sharp opinion, and enlightening conversation. Help us shape our ongoing coverage by responding to a short reader survey.