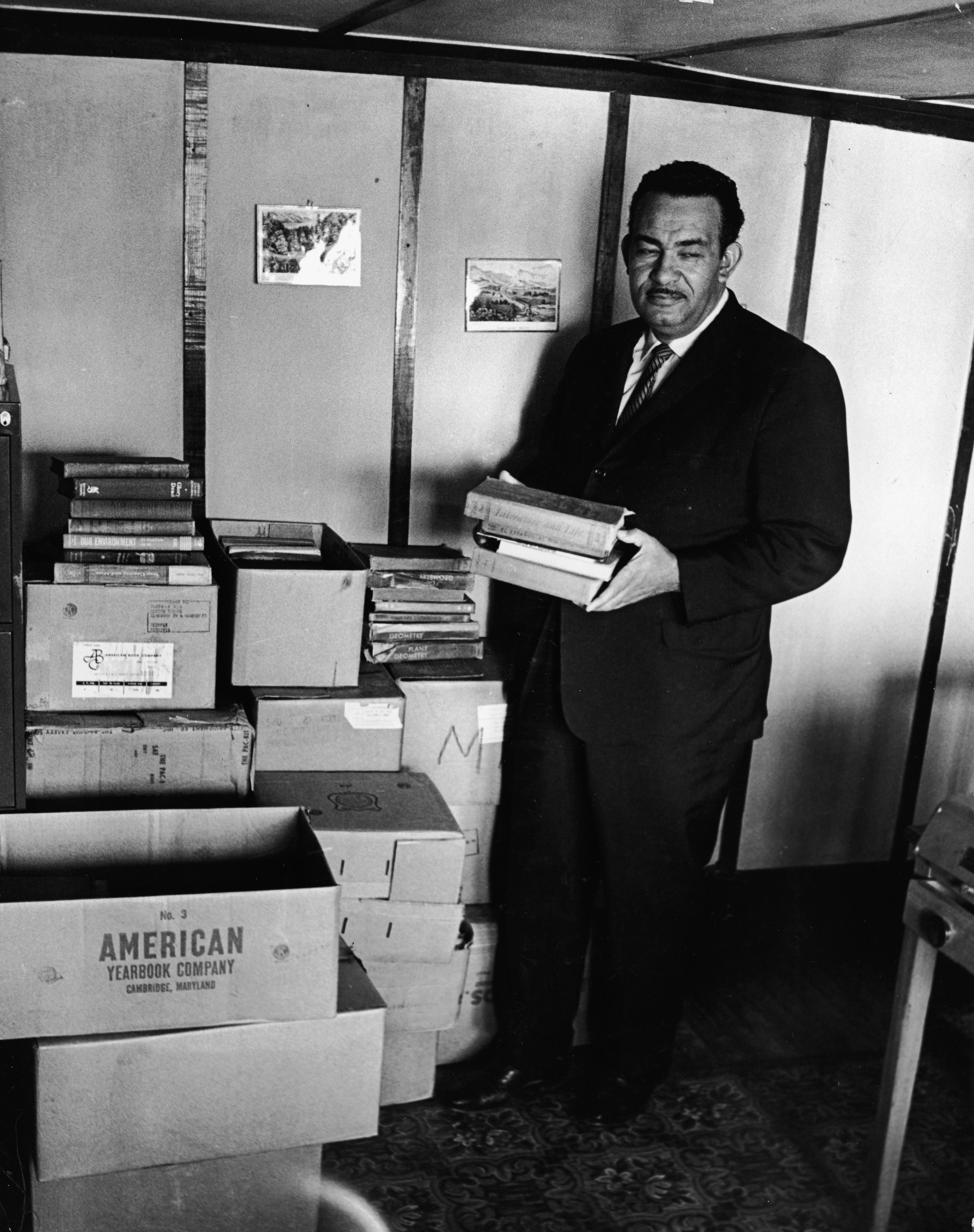

(Photo: Express Newspapers/Getty Images)

In 1979, a 22-year-old reporter named Ken Woodley graduated from college and moved home to Prince Edward County, Virginia, for a job at a family owned local newspaper, the Farmville Herald. Soon after, as he recalls in his memoir, The Road to Healing: A Civil Rights Reparations Story in Prince Edward County, Virginia, he was sitting at his desk when a local woman passing through the office hurled a question at him: “You know what happened here, don’t you?”

Woodley didn’t know what the woman meant, but he soon found out. In 1954, the Supreme Court ruled on Brown v. Board of Education, after which Prince Edward County, along with every other county in America, was ordered to end the racially segregationist practice of “separate but equal” public education. The presumption was that schools would integrate.

In Virginia, however, white leaders came up with a new plan, one that they called Massive Resistance. Rather than ending segregation, they shut down public education altogether, diverting much of the relevant public funding to vouchers that white students could use at all-white private schools.

In much of Virginia, Massive Resistance was brought to an end in less than a year by court orders. But in Prince Edward County, the school shutdown persisted for five years, and deprived an estimated 2,200 black students of an education. About 250 white students also got caught behind the exclusionary fence. Black families who wanted their kids to keep being educated were forced to move. For any child whose parents couldn’t afford to flee, it was the end of schooling, at least for several years, and in many cases for life.

Woodley is white, and he writes that learning about Massive Resistance for the first time came as a profound shock. Just as troubling was his discovery that his employer, the Herald, had been a prominent supporter of the policy, with the paper’s owner-publisher having written numerous editorials in support of Massive Resistance. Two decades later, the Herald had the same owner-publisher, and he was still writing the editorials.

Woodley was appalled, but he stayed at the Herald. For decades, he avoided actually reading the pro-segregation editorials he knew his employer had written, fearing that they would disturb him too much. He rose through the ranks at the newspaper, eventually becoming the editor and the lead editorial writer. In 2003, when the Virginia General Assembly was working on a resolution of apology for its legislative role in facilitating Massive Resistance, Woodley had an epiphany: An apology wasn’t good enough. The state, he felt, should also be offering reparations to individual citizens who were harmed by Massive Resistance. What better than educational scholarships? And who more fitting than he, the editorial writer at the Herald, to lead the charge?

By 2004, Woodley’s ambition had become a reality: The state legislature had set aside $1 million (with another $1 million contributed by a private donor) in scholarship funds—for GED classes, community college, four-year degrees, and master’s programs—that would be made available to any Virginia residents who’d been directly affected by Massive Resistance as children.

(Photo: NewSouth Books)

This is a vital story, one ripe for attention. Back in 2014, when the writer Ta-Nehisi Coates published his blockbuster essay “The Case for Reparations” in The Atlantic, it felt like the idea of material atonement for the enduring ravages of slavery and Jim Crow might finally get a new and favorable hearing in the American mainstream. That never came about. Part of the reason is that, for many readers, reparations via sweeping acts of Congress (like those that Coates was calling for) are just about impossible to imagine. If they are ever to become a reality, I suspect it will be thanks to a mutually reinforcing feedback loop of smaller-bore initiatives, with national efforts strengthening the local and vice versa.

Unfortunately, we hardly ever hear about local examples, leaving the conversation about racial reparations in America almost totally hypothetical, uninformed by the texture of real life and real political battles. Woodley gives us a chance to see one small reparations initiative go from dream to reality, and ponder its connection to the broader project.

Despite its obvious national resonance, The Road to Healing is published by a small Alabama press, and it sometimes feels written more for local posterity than anything else. The vast bulk of the book is taken up with zoomed-in, play-by-play descriptions of the scholarship fund campaign: Who Woodley called on what day; the time he bumped into this legislator; the time he wrote to that legislator; who agreed to what, and when; all the small compromises that go into passing any law. On one hand, this makes the book a valuably detailed portrait of the complexities of real-world change. But too often, the extensive focus on procedure makes the story feel like a calendar of appointments—or like a boring episode of The West Wing.

This shortcoming might have bothered me less if, in pursuing his idea of instituting restorative scholarships, Woodley had done more to involve its intended beneficiaries. In the book, he does offer biographical sketches of a few surviving victims of Massive Resistance, and it’s clear that these Virginians support his campaign for reparations. Today, most of the scholarship funds have been put to their intended purpose. But there is little sense that Woodley truly gave these individuals a chance to exercise a shaping influence on the reparations campaign. For example, we never see him making any systemic effort to figure out which compromises Resistance victims view as acceptable, or what they think might be the best strategy. On the day of the bill’s ceremonial signing, over 100 black Resistance victims rally at the Virginia statehouse to help convince the General Assembly to make the proper funds available. But other than that, I could make out little sense of substantive, sustained engagement between the reparations campaign and the community on whose behalf it was waged.

I mention this not to pick on Woodley or his book, nor to diminish the importance of the scholarships that he helped call into being. It is clear that the Prince Edward County scholarship battle is the defining effort of Woodley’s life, and The Road to Healing is inspiring stuff: a true tale, in which the rickety gears of legislation are used to tilt the world a tiny bit closer to justice. (Plus a stirring testament to the power and value of small-town newspapers.) But if the bigger goal, as Woodley recognizes, is reparations on a broader scale, it seems important to recognize that the template here—an individual white man prevailing upon legislators, largely disconnected from a social movement that strengthens political demands from the ground up—is likely to be of limited value going forward.

What it will take is something akin to what Prince Edward County’s white leaders were able to call into being in the aftermath of Brown, when they felt called to defend what was most important to them. Their aims were wrong, but the name—Massive Resistance—still has a nice ring to it.

Pacific Standard’s Ideas section is your destination for idea-driven features, voracious culture coverage, sharp opinion, and enlightening conversation. Help us shape our ongoing coverage by responding to a short reader survey.