Jessica Pan was sitting alone in a sauna, fully clothed, when she realized that depression and loneliness had been destabilizing her entire life. With only a day left in her gym’s weight-loss competition, she had stepped into the sauna in a last-ditch effort to shed some water weight and thereby end her year-long streak of “[feeling] like a loser.” After stewing in the heat and yelling at a spa assistant, Pan realized in a panic that her desperation to clinch this minor fitness victory was fast unraveling her mental state.

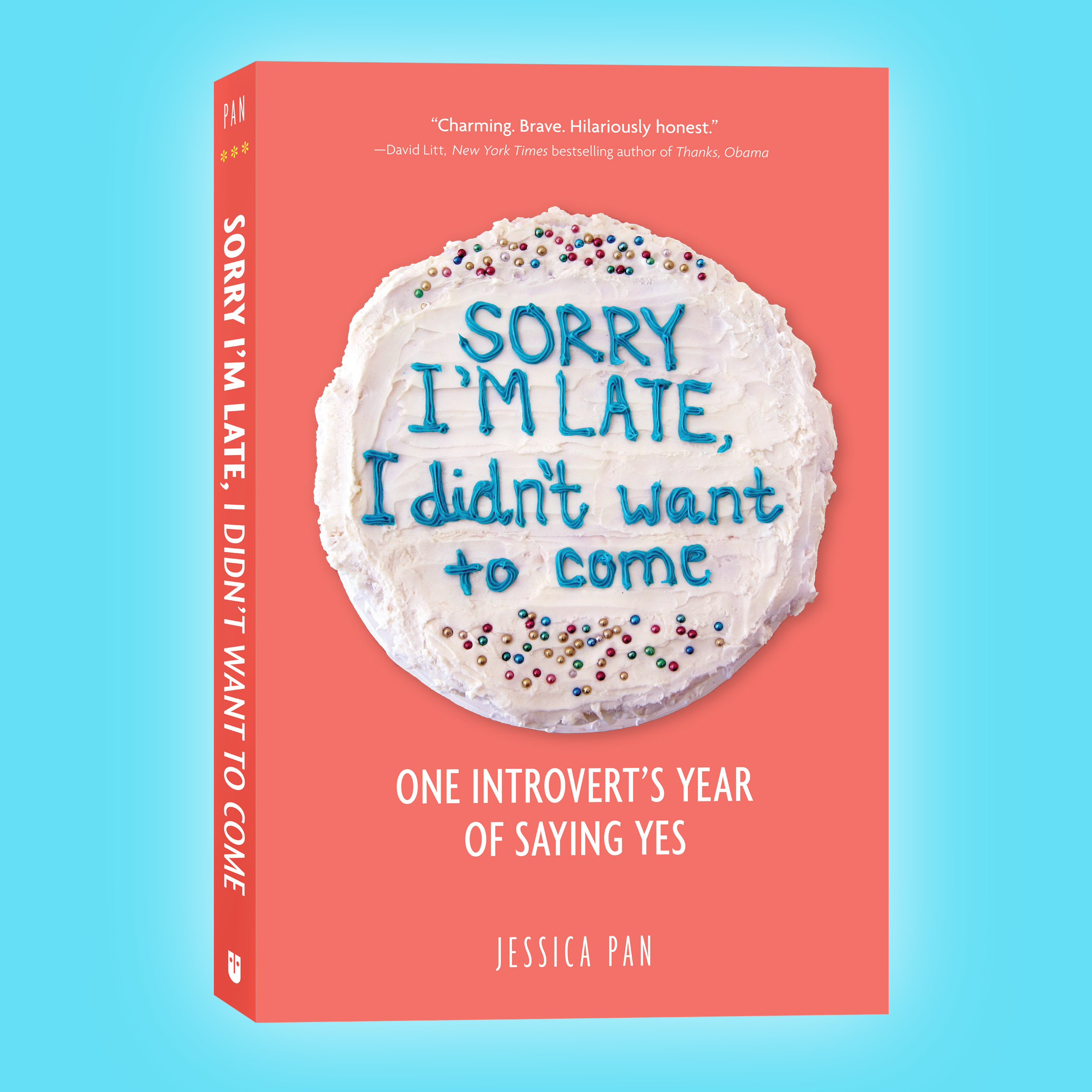

“I had completely lost perspective,” she writes in her memoir, Sorry I’m Late, I Didn’t Want to Come: One Introvert’s Year of Saying Yes. “I had managed to wedge myself into a hole, through fear, insecurity, and stagnation.”

Pan’s moment of crisis in the sauna was perhaps the most dramatic point of her depression, but she says her anxieties date much further back. A freelance journalist in her thirties who had recently moved to London before the events described in the book, Pan tells me that discontent had begun to pervade her quiet, and increasingly isolated, life.

“I was 32, which is typically the age when we start losing our friends. I was in this big city that wasn’t that friendly. All my friends were having babies or they moved away. And it just kind of hit me: ‘Oh my God, I’m lonely.'”

(Photo: Ian Cook)

Alarmed by this revelation, Pan vowed to radically alter the way she lived. A longtime introvert, she decided to throw herself out of her natural shyness and into hyper-social situations, in hopes of meeting new people and of subverting her lifelong tendency toward seclusion. Sorry I’m Late, I Didn’t Want to Come chronicles a year of Pan’s life as she nose-dives into extroversion, attending adult friendship mixers and performing at public speaking events. It also includes advice from the public speaking coaches, psychologists, and complete strangers whom she met along the way. Gritting her teeth through introductory improv workshops and Bumble BFF dates, Pan shines as a witty narrator and recounts with caustic, self-flagellating humor this year-long effort to manage her immense social anxiety.

Pan’s memoir grapples with the detrimental mental-health effects of long-term loneliness, and the frequent embarrassment of searching for human connection. There are moments when Pan’s stabs at meaningful interaction leave her feeling more isolated than ever, as she fumbles with social skills that everyone else has seemingly acquired with ease. During some parts of the book, as when Pan shares extremely private confessions in a “conversation workshop” or tears up at her public speech rehearsal, her social growing pains can conjure excruciating secondhand humiliation, even fear, in the reader.

But Pan’s feelings of depressed loneliness, and the circumstances that precipitated them (moving to a new city where she had few friends, having limited daily contact with family and loved ones, struggling to form close bonds) are far from unique to her. Though the book is anchored by her own story, Pan calls attention early on to the larger social structures that foster widespread loneliness among modern adults. She points to the normalization of staying in and using social media as modes of emotional fulfillment, suggesting that our unlimited online engagement is a “failed substitute” for real human interaction. She draws from anecdotal and empirical evidence to emphasize how common it is for adults these days to feel as though they have no close friends. Pan is hardly alone in asking the question, “Where do you go to make friends when you’re an adult?”—and Sorry I’m Late, I Didn’t Want to Come is the result of her quest for a meaningful answer.

(Photo: Andrew McMeel Publishing)

Happily, for Pan and reader alike, her story is ultimately triumphant, and ends with Pan having found meaningful friendships and a braver, kinder version of herself.

“I had thought before that I was chained to my same anxieties and personality for the rest of my life,” Pan says. “But my definition of myself had expanded. It’s so cliché, but knowing that I was capable of change and doing things I never thought I would opened up my world.”

Pan is careful to add that the message of her book is not simply that new people and experiences will cure depression.

“I wasn’t depressed because I was an introvert,” says says. “I was depressed because, over the years, I had used the label ‘introvert’ to say no to things that involved lots of other people, or or any new people, and I had been really limiting myself and my life experiences.”

The optimistic ending of Sorry I’m Late, I Didn’t Want to Come offers a picture of a more interconnected way of living, and of a warmer, more flexible version of one’s self. At the same time, Pan warns readers against giving into instinctual fears of appearing vulnerable or desperate. Actively pursuing friendship and connection in adulthood can sometimes feel embarrassing, or even like failure, Pan acknowledges. But once you push beyond this initial uneasiness, she insists, you’ll find that “people are kinder and more understanding than we think they’re going to be.” Sorry I’m Late, I Didn’t Want to Come admonishes us against accepting a society characterized by lonely self-consciousness, where everyone sits alone and half-heartedly waits for someone, anyone, to wave hello.

Pacific Standard’s Ideas section is your destination for idea-driven features, voracious culture coverage, sharp opinion, and enlightening conversation. Help us shape our ongoing coverage by responding to a short reader survey.