When Jeremy Slack got a call from an activist at a soup kitchen for deportees in Sonora, Mexico, in the spring of 2013, he knew what he had to do. Juanito, a soft-spoken young man in his twenties, had been deported. Slack had first met Juanito in a prison in the United States in October of 2012, when Slack was a researcher with the University of Arizona’s Center for Latin American Studies. Slack and a journalist friend rushed to the border with a video camera to record an interview, which Juanito himself had requested, in case something were to happen to him again. (Juanito is a pseudonym.)

For the next three hours, they sat in a migrant shelter while Juanito, his legs shaking, spoke at length about being kidnapped, extorted, and tortured by the Zetas cartel, one of the most notorious drug trafficking organizations in Mexico. He described having his fingernails pulled out and being forced to cut bodies open to extract organs the cartel could traffic. But after seven months in captivity, Juanito had managed to escape. While on a mission to transport marijuana across the border for the cartel, he deliberately left tracks, thinking that his only chance at survival would be for U.S. Customs and Border Protection to find him. And it worked: Juanito was apprehended and sent to serve time in prison until his deportation in 2013. So when Juanito and Slack reunited in Mexico that year, he knew the cartel could get him at any moment.

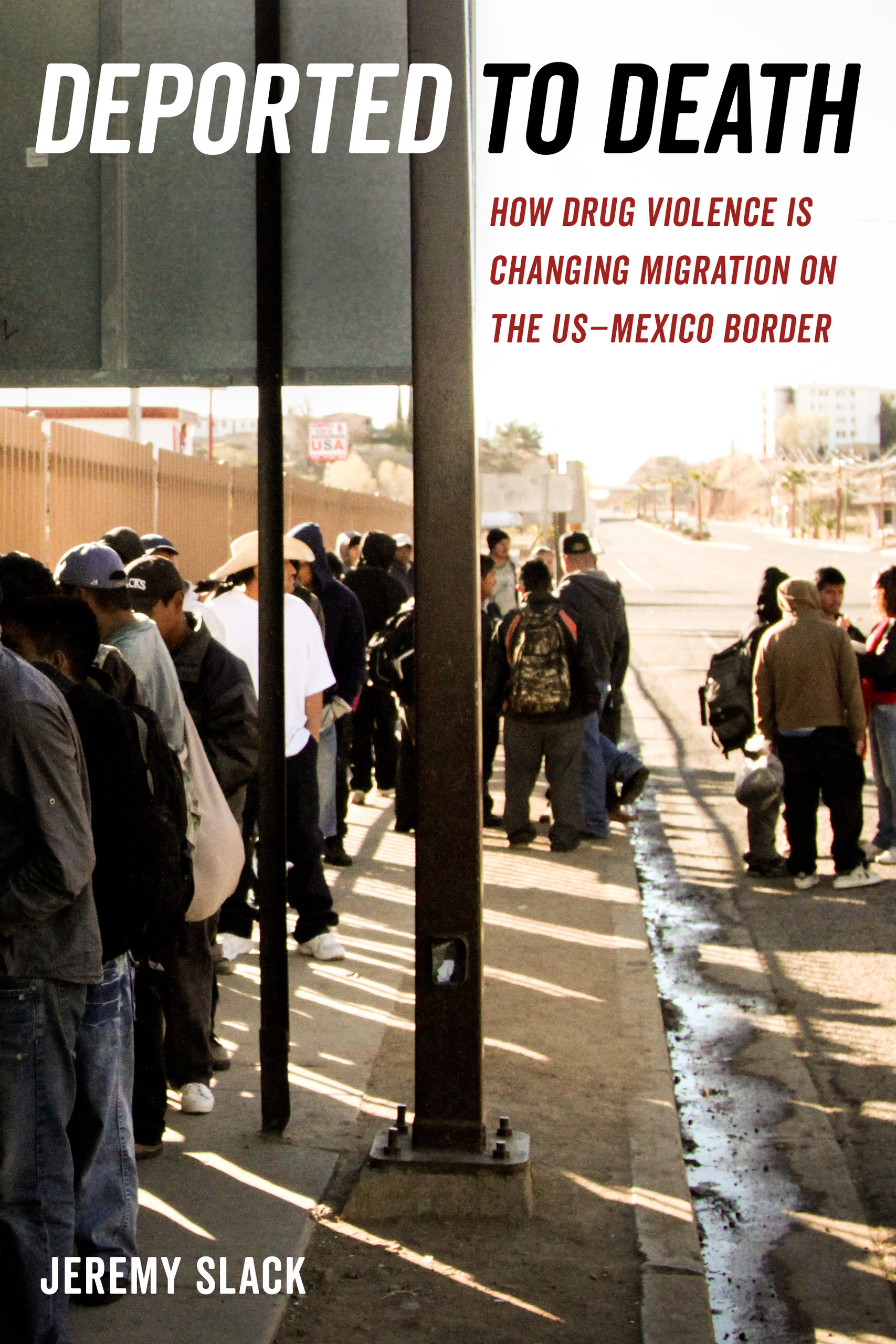

(Source: University of California Press)

Between 2009 and 2012, Slack, an assistant professor in the Department of Sociology and Anthropology at the University of Texas–El Paso, and a group of researchers conducted in-depth interviews and surveys with 1,100 recently deported migrants in six cities in Mexico for the Migrant Border Crossing Study. Now, Slack has written Deported to Death: How Drug Violence Is Changing Migration on the U.S.–Mexico Border, in which he explores the ways that border enforcement and mass deportations to Mexico—where 37,000 people are currently missing or have been disappeared—are making migrants increasingly vulnerable to criminal organizations and generalized violence.

“There is an important way in which a transnational impact of a war on drugs, on crime, and on immigration is going to affect both sides of the border,” Slack says. “When you have people that are essentially products of our arcane systems and they get kicked out, whose fault is that?”

Pacific Standard spoke with Slack about the human consequences of recent U.S. immigration policies, the stigmatization of deportees, and why it can be so hard to answer one seemingly simple question: What happens to the people who are being sent back?

It seems like your work is becoming more relevant by the minute.

Unfortunately, yes [laughs]. It’s certainly a scary thing for me. We’ve seen this administration taking every possible step to make people more vulnerable, more exposed to violence, and facing greater threats along the border. And I think it’s just getting started.

That’s not a very optimistic outlook.

No. This interview will probably suffer from a lack of optimism.

Your book focuses on an overlooked population: deportees. What helps explain why these narratives are so often missing from the public eye?

It’s a really good question, and I don’t know if I have a solid answer. I think part of it is that we’re suffering from a “blank map syndrome”—we talk about migrants crossing the border, but once they are removed, they disappear from people’s imaginations. And a lot of the same prejudices we see dominating discourse on immigration also affect deportees. That idea that to get removed you probably had to do something bad, that there is some moral failure with these people. What did they do?

This is something you see repeated in Mexican border cities, where anti-immigrant policies are growing in popularity. There’s a lot of anger brewing, and it’s easy to turn around and blame people who are trying to protect themselves when we’re the ones setting up a system designed precisely to keep people out and to punish them for attempting to seek aid.

So what is the image of the deportee that you have actually found?

Deportees are typically very connected to the U.S. In our work, the number of people who have U.S. citizen children was about 23 percent and, on average, they spent over 10 years in the U.S. The people being removed are intimately connected to this country.

Is it fair to say that the border is also a character, or at least a vector, through which to tell the human stories in your book?

Definitely. As a geographer, the relationship between people and space is very important to me. People have different relationships to that border. I have a lot of privileges in the ways that I’m allowed to cross back and forth, whereas potential migrants and deportees are treated in a different way. That means people who are deported and living along the border are marked by that relationship in a fairly extreme way—they’re rejected by the border and, therefore, seen as a different type of person.

We talk about these direct forms of violence, which are very important and real, but underneath that, there is a hidden violence. People are just lost, essentially exiled in a place where they have no support. That’s a population no one is going to come looking for. And organized crime knows that deportees often lack context in Mexico and can be easily coerced into joining a cartel when given the choice of being tortured or held for ransom and working for these groups. At that point, they are stuck in this even more brutal cycle of violence.

So in a way, deportees become at once a reject and an asset for crime bosses.

Exactly. What can we use this group of people for? What can we get from them? Having more and more people who are desperate in their own right is a big support to keep the [drug war] going.

How did being surrounded by violence affect your work and methodology?

I spent many years along the border going wherever I pleased and not really thinking about security issues. And then it changed quite abruptly. Shootouts in daylight, kidnappings proliferating—all these things we associate with that period of the drug war in 2008 started happening.

At the same time, I’m interviewing a lot of people who are crossing the border and who have a front row seat to this violence. A lot of it was a process of slowly building up contacts and making myself visible, moving into the [Nuevo Laredo] shelter for a month. I didn’t just pull out recorders and notebooks right away in public places. But it certainly takes a toll. I think the issue of feeling rather impotent in front of so much violence and so much danger is a real challenge.

In the first chapter, “The Violence of Mobility,” you mention the San Fernando massacre [the killing of 72 migrants by the Zetas cartel in Tamaulipas in 2010]. What is the importance of that episode?

This was really the event that put the fact that people were being killed for being migrants into the public imagination for the first time. People were aware of migration as dangerous, but it really wasn’t known or acknowledged that simply being a migrant could get you murdered. Now, did it actually change politics of corruption and migration in Mexico? I would say no. This is one of those horrific tragedies that is going to be another footnote in this horrible war on drugs.

I’m not the first person to point out that prohibitions on movements are going to attract organized crime and a certain level of violence. But especially at this moment in time, when we see what was considered a progressive candidate for president [Andrés Manuel López Obrador] really falling back into the policies that led to that [2010] massacre, it leaves one little hope that we will stop seeing these types of killings.

And that was all prior to the “Remain in Mexico” policy or the safe third country rule.

It’s terrifying. [These policies] are just basically taking all the issues that I’ve been studying and writing about and throwing gasoline on it. I can’t think of a worse way to cause more violence and insecurity along the border. We’re seeing people who have been returned to wait for their case in Mexico, and they run into the same gang member they testified against in El Salvador on the streets. These are not safe places—Tijuana is the most dangerous city in the world, and Juárez is number five. [In 2010, more than 3,000 people were murdered in Juárez, according to Mexican authorities.] We can’t expect tens of thousands of women, children, and families to wait in these cities without resources and not get preyed upon.

We’re really enacting policies that seem designed to create more violence along the border and essentially help organized crime. It’s completely backwards. The very fact that [the “Remain in Mexico” policy] is called the Migrant Protection Protocol is absurd. I’ve never even heard anyone try to argue that this in any way protects migrants because it’s not designed for that. We’re now doing surveys in Juárez and Tijuana to understand what types of violence people have been exposed to as a result of having to wait in Mexico. It’s just getting started, but it doesn’t look good.

What do you see as some of the challenges and possibilities for research in this field?

My next big goal is to find out what happens in five, 10, 15 years after people are deported to really understand what are the long-term impacts. What does it do to people? What happens to their families in the U.S.? What happens to people who lost one or both parents to our immigration system?

We set up a system where it’s so easy to get rid of people, and there is an assumption that they are going to remain safe. I really want for people to understand that deportation is not harmless. It creates a lot of damage, both in terms of immediate harms that people face, but also the long-term impact of this mass removal strategy for immigration. We shouldn’t be as blasé about removing people. The idea that we can throw people into another country and have nothing come back on us is a fantasy.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Pacific Standard’s Ideas section is your destination for idea-driven features, voracious culture coverage, sharp opinion, and enlightening conversation. Help us shape our ongoing coverage by responding to a short reader survey.