The average American has no clue how large the national debt is — or even that the national debt is worth thinking about as anything other than a vague problem for the far-off future. He lives his life, pays his taxes and enjoys his local pork-barrel projects, blissfully unaware that the people in charge of the federal government are, financially speaking, running it into the ground.

If you or someone you know is as fiscally uninformed as most of the country (and unless you’re an economics professor married to a think tank researcher, you probably are), please, for the sake of your children and their grandchildren, go see the movie I.O.U.S.A.

Writer/director Patrick Creadon and co-writer/producer Christine O’Malley, the team behind Wordplay (2006), chose the unsexiest subject imaginable for a documentary: deficit reduction. As Robert Bixby, executive director of the deficit-hawk Concord Coalition, tells viewers, talking about it is like “taking a cold shower.” Yet the film nails its seemingly impossible task, explaining America’s looming fiscal crisis in a way that even a child could understand and adding just enough self-deprecating humor that it doesn’t feel like a dry, professorial lecture.

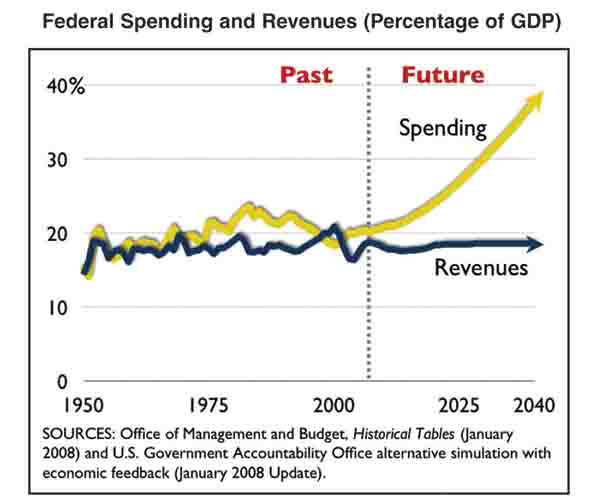

It covers a lot of ground in 85 minutes, but the central theme is simple — the American people and their leaders are living and spending far beyond their means. The overarching trend is typified by the exploding national debt, which has doubled since George W. Bush took office. The $9.7 trillion liability is the result, says the Concord Coalition’s Harry Zeeve, of a schizophrenic policy: “We’ve got a big-government spending program and a small-government tax program.”

Creadon orients much of the film around the story of former U.S. Comptroller General David Walker, who served under four presidents — Reagan, Clinton and both George Bushes. This federal government super-accountant is the ultimate technocrat. He might be Karl Rove’s better-looking, moderate twin brother, desperate to save America from itself.

Several reviewers have compared I.O.U.S.A. to An Inconvenient Truth. Yet as boring as Al Gore seemed as a politician, the environmental documentary humanized him in the eyes of a vast audience. Creadon doesn’t quite succeed in portraying Walker as a three-dimensional character; viewers learn only that he’s brilliant, he loves America and his grandchildren, and he believes we’re careening toward economic ruin.

I.O.U.S.A. lacks the dramatic narrative, colorful characters and cinematographic beauty of great documentaries. Sure, there is a handful of hilarious moments, notably from Congressman Ron Paul, R-Texas, who exhibits the know-nothing charm that elevated him to cult hero status during the Republican presidential primary debates. Yet what makes this otherwise mediocre film an outstanding achievement is its brilliant use of data and graphics to scare the bejesus out of viewers.

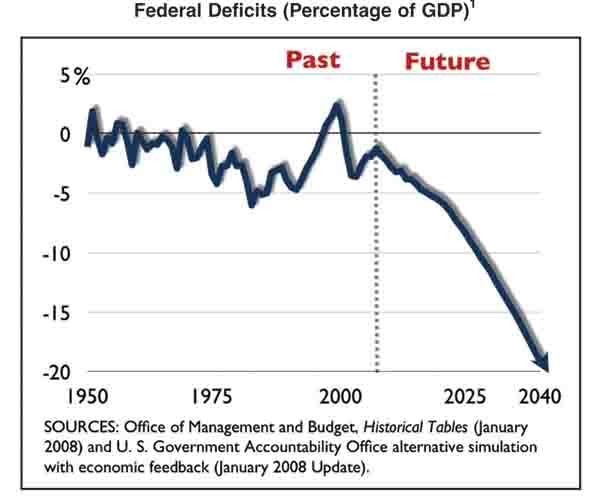

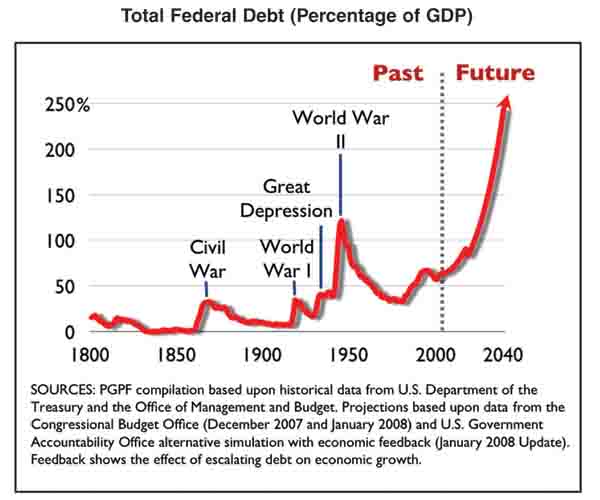

That a picture is worth a thousand words is obvious; I.O.U.S.A. proves that an infographic is worth about $10 trillion. Simple, computer-generated images show the audience exactly how much is being wasted, lost and overpromised every year, fostering an appreciation of the sheer scale of the crisis.

Video: Watch the “I.O.U.S.A.” trailer

A slew of alarmist books — including Empire of Debt by Bill Bonner and Addison Wiggin (another of the film’s writers and executive producers) and Running on Empty by former Secretary of Commerce Peter G. Peterson — have failed to register beyond a small community of pessimistic wonks. It’s difficult to convey how dire it is that Medicare, Medicaid and Social Security will consume the entire federal government by 2050. Or that our $800 billion-plus trade deficit is the highest in the world, while China and oil-exporting states sit with trade surpluses. Or that by the time children born today start families of their own, the national debt will amount to 244 percent of our entire gross domestic product — two and a half times the size of all goods and services bought, sold and traded in the whole U.S. economy.

When moviegoers see it all on pie slices that swallow a whole pie chart or bar graphs that must zoom out hundreds of times to display ballooning deficits, they gasp. The film uses similar techniques to concisely explain subjects Americans should comprehend but don’t, such as how the Federal Reserve controls the money supply and why that affects the economy.

Some of the most damning moments highlight what Walker calls the “leadership deficit” — politicians’ seeming inability to lead us toward solutions to budget, trade and savings deficits. The best comes in the film’s opening scenes, during which a series of modern presidents’ State of the Union addresses is edited together into one long, disingenuous speech about belt-tightening and making good on fiscal obligations.

Much of the nightmarish deficit depths have arrived on George W. Bush’s watch, and the only recent president to run a surplus was Clinton. A more partisan film might have gone for Bush’s jugular and hyperbolized Clinton’s contributions, but I.O.U.S.A. holds back. After all, Democrat-controlled Congresses have raised few complaints in annually raising the debt ceiling to its current $10.6 trillion (likely higher if the pending economic disaster package passes), and Clinton only balanced the budget by compromising with the Gingrich Republicans.

While the filmmakers don’t divulge their own political opinions, it seems as if they’ve bent over backward not to produce a lefty anti-Bush screed. Centrists (like Walker) and conservatives are well-represented in the interviews, but the liberal perspective is mostly absent. Diversity clearly wasn’t a focus: I.O.U.S.A. features just a handful of women and almost no people of color. (There are more Asians in front of the camera than Asian Americans.) Oddly enough, this white-bread cast strengthens the argument: These people have been wildly successful in business and/or risen to the top of the Washington establishment. Most have no ax to grind, partisan or personal. Who better to deliver the message that the system is completely broken?

Walker makes it clear, too, that we can’t just blame the elite for bankrupting the government on our behalf. Postmodern American workers, it turns out, can’t save a dime. In 2005 and 2006, Americans spent more money than they took in — a negative savings rate — for the first time since 1934. The figure recovered to a savings rate of about 1 percent in 2007. (By comparison, Americans saved about 13 percent of their income during the 1970s, and the Chinese now save 40 percent of their income.) Even as the government is selling treasury bonds to China, we’re greedily buying cheap Chinese goods with borrowed dollars.

As bad as things look now, though, they’re going to get much worse when the baby boomers retire and Social Security and Medicare costs catapult. Sen. Judd Gregg, R-N.H., says it’s the “potential fiscal meltdown of this nation.” Yet we’re either procrastinating or in complete denial. “Obviously, if the public doesn’t understand, there’s going to be no sense of urgency and no pressure on our colleagues or on the White House to act,” says Sen. Kent Conrad, D-N.D., the ranking member of the Senate Budget Committee.

Conrad’s insight is the center of the unfortunate paradox that Creadon’s film implies but does not really drive home. On the one hand, the politicians have failed at their fiscal duties. Voters, however, demand low taxes and big spending, tying the hands of those in office. Walker, Bixby and the filmmakers assign blame to all and suggest citizens rethink their expectations of government.

As for specifics on the solution, the film is better at telling us what won’t work than what will. Doubling taxes might close the funding gap but remains politically impracticable. Liberal dreams of ending the Bush tax cuts and pulling out of Iraq would only save 13 percent of what’s necessary to provide a fix. The estimated unfunded liabilities of the government, after all, work out to $175,000 per person living in the United States.

The just-released companion book (also called I.O.U.S.A.), by Wiggin and producer Kate Incontrera, adds some details. A first step might be reinstituting pay-go rules, which required new revenue or funding cuts for every spending increase by the federal government. (The rules expired in 2002.) They also suggest comprehensive entitlement and tax “reform,” which would likely require huge program cuts and tax raises.

The book itself is an odd document, partly reverse-engineering the film into a sort of informal textbook, partly providing a behind-the-scenes look at the filmmaking process. It lacks the verve of the movie and does a comparatively feeble job of explaining concepts the filmmakers conveyed so intelligibly. Yet for econophiles, it’s worth checking out just for the 150 pages of interview transcripts from filming, which provide what amounts to a mini-oral history of the last 40 years of economic policy.

Few other venues allow such a large cast of financial characters, ranging from ex-U.S. Treasury Secretary Paul O’Neill to billionaire investor Warren Buffett, to answer simple economic questions and describe complex financial issues, unfiltered and (it seems) largely unedited. The best journalists know that if you let anyone pontificate long enough, he or she will eventually stop spouting talking points and start opening up. That’s exactly what happened here, and some stellar material ended up on the cutting room floor.

In its last several minutes, the film becomes a bit of an infomercial for Walker’s current employer, the Peter G. Peterson Foundation, a young good-government organization that bought the rights to distribute the movie last year. The bulk of I.O.U.S.A., though, is a clarion call in which some very serious people rightly argue that we’re in for very serious trouble.

A few months before its Sundance Film Festival premiere, horrendous events stemming from the subprime mortgage bubble made the film seem ever more prescient. Unfortunately, the U.S. now struggles with the most serious economic catastrophe since the Great Depression. Yet this calamity may induce America to learn a little about the financial system or even put aside some money for a rainy day. And perhaps, if things get bad enough, we’ll stop demanding that our government write checks its people can’t cash.

As Des Moines Register political columnist David Yepsen tells the audience, “This is America. We don’t do anything until it reaches a crisis.”

Sign up for our free e-newsletter.

Are you on Facebook? Click here to become our fan.