How do you quantify climate vulnerability? It’s a devilish and important question at the United Nations climate talks in Paris, as negotiators seek to determine the flow of aid from developed economies to at-risk states. These negotiations are already hitting points of tension: Representatives from the West have been tight-fisted so far in their offers of assistance to developing countries, slowing progress on the COP21 draft that Laurent Fabius—president of this year’s conference—has requested by Saturday.

Into this mix comes a clarifying new paper from Germanwatch: the 11th edition of the Global Climate Risk Index, an annual report that offers critical insights on which countries are most susceptible to the impacts of climate change. Germanwatch is traditionally careful to circumscribe its deep reports with plenty of caveats. The Risk Index “must not be mistaken for a comprehensive climate vulnerability scoring,” cautions this year’s edition. Instead, the GCRI aims “to contextualize ongoing climate policy debates—especially the international climate talk—with real-world impacts of the last year and the last 20 years.” Asterisks and all, the index is deeply informative, aggregating data gathered by Munich Re NatCatSERVICE on extreme weather events all over the world, emphatically not including “geological factors like earthquakes, volcanic eruptions or tsunamis … because they do not depend on the weather.”

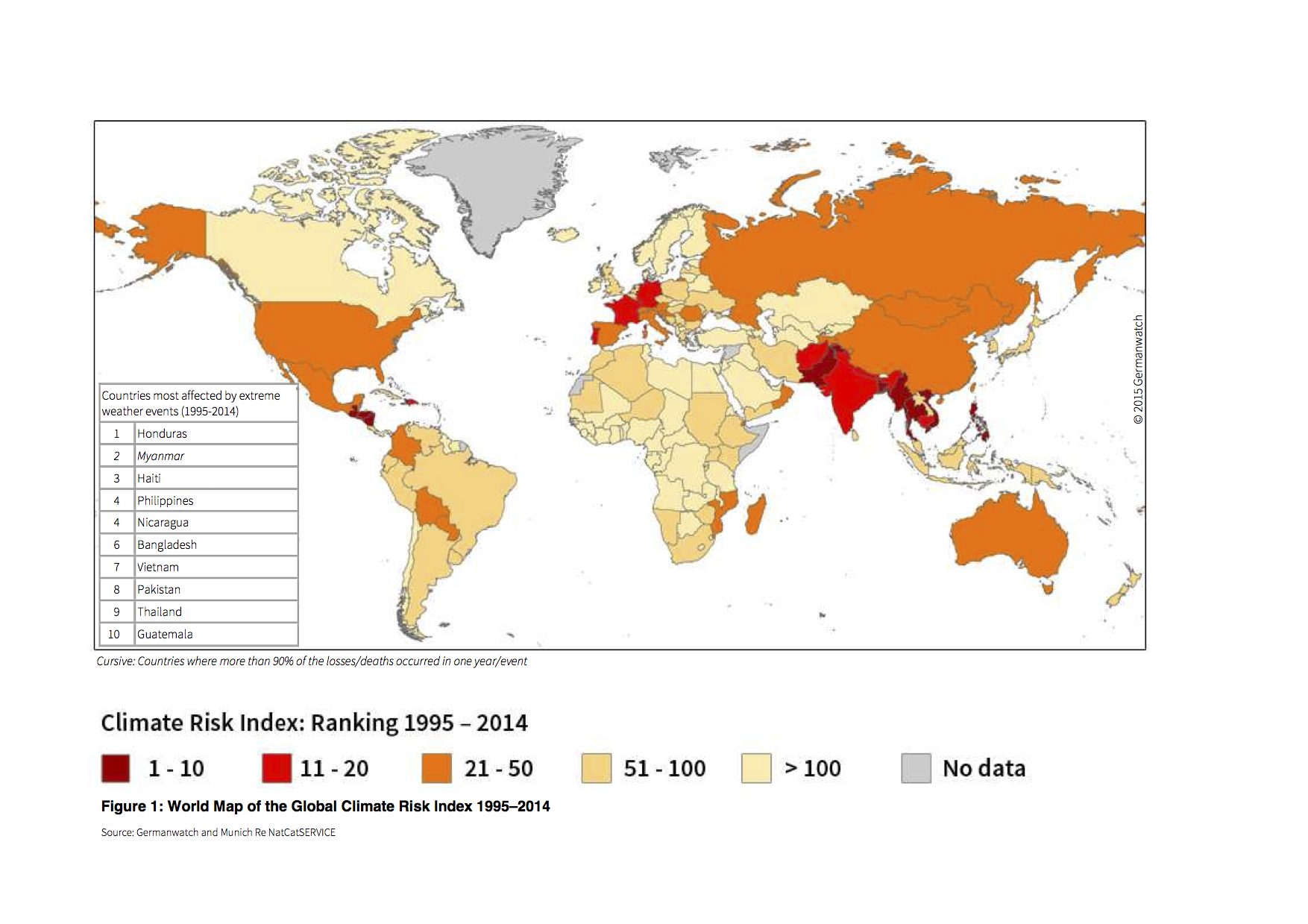

In other words, while these rankings do not claim to be definitive, the numbers you get from Munich are born of sound methodology. And while it might be impossible to quantify climate vulnerability, you can map it pretty convincingly:

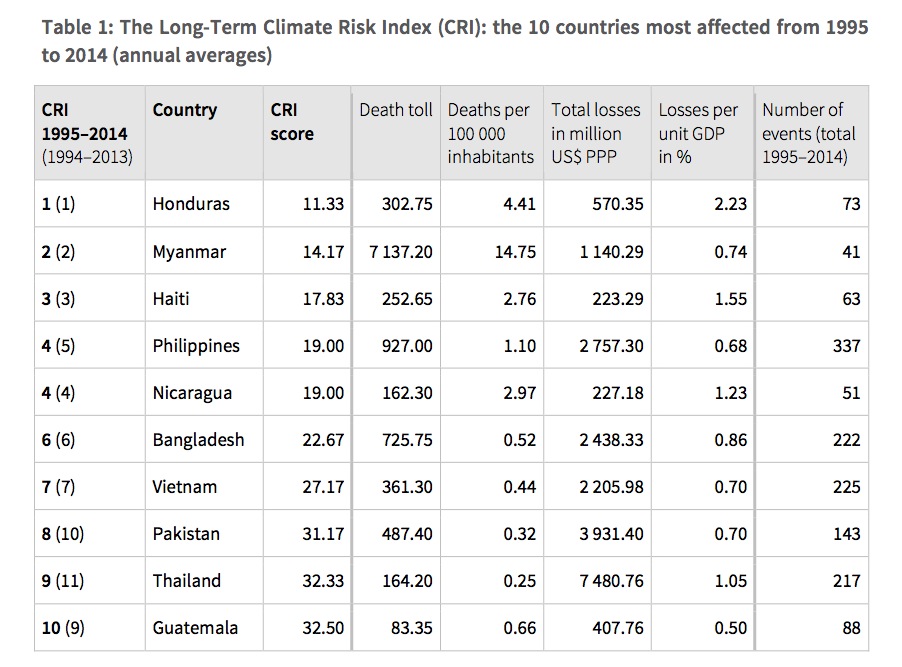

From 1995 to 2014, the countries most affected by climate events were Honduras, Myanmar, Haiti, the Philippines, Nicaragua, and Bangladesh. Below, you can see the aggregate findings from Munich and Germanwatch, which include the death tolls in these countries from extreme weather, the total losses of purchasing power, and the losses per unit GDP:

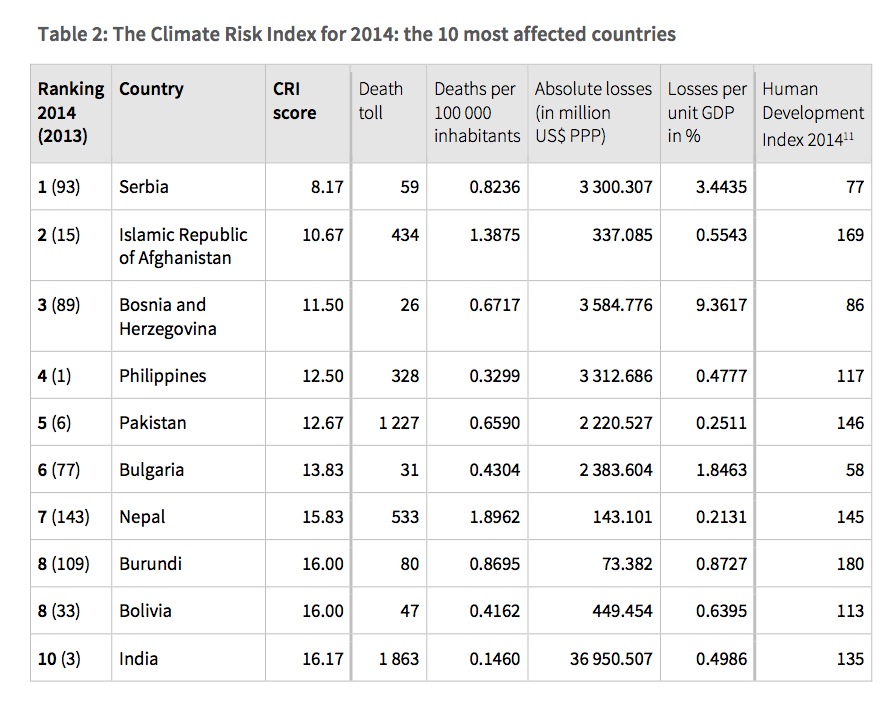

On the shorter term, 2014’s biggest climate losers were Serbia, Afghanistan, and Bosnia and Herzegovina—followed closely by standbys such as Pakistan (#8, above) and the Philippines (#5, above):

“It was the poorhouse of Europe that was the worst hit last year,” says Sönke Kreft, author of the study and leader for international climate policy at Germanwatch, adding that “heavy rains, flooding, and landslides have been the defining hazards of the new Global Climate Risk Index.” Kreft’s “poorhouse” comment fits nicely within his lexicon of dramatic inequality: “Climate-related impacts are unfair; nine out of ten most affected countries [between 1995 and 2014] are among the low or middle-income countries.”

Still, as we see from the map above, even some of Europe’s richer countries rank high in weather-related catastrophes over the past 20 years. (The report’s entry on Europe singles out the 2003 heat wave, which claimed “tens of thousands” in France, Italy, and Germany.) There’s a big difference, though, between Germany’s capacity for domestic re-construction and Serbia’s; a yet greater difference between Germany’s and Myanmar’s. Just because you see bits of Europe colored red does not mean that climate change is equitable.

The GCRI is comprehensive in its analysis—the numbers for 1995–2014 were culled from research on 15,000 extreme weather events—and its findings are persuasive in their unapologetic focus on the human cost, not just economics. (Too often, international assessments focus primarily on the money.) Kreft and his team have also issued policy recommendations, including a wholesale endorsement of a robust G7 Climate Insurance Initiative—a project that President Obama has pledged to support with $30 million, and which promises to help safeguard up to 400 million of the poorest and most vulnerable victims of climate change over the next five years.

Toward the close of this morning’s panel, Kreft reminded us that any time you see countries ranked, “there should be an application of a pinch of salt.” Still, he stands by the GCRI findings: “Nobody should be left behind in Paris.”

If the talks falter next week, those charts above tell you exactly whom we will have left behind.

“Catastrophic Consequences of Climate Change” is Pacific Standard‘s year-long investigation into the devastating effects of climate change—and how scholars, legislators, and citizen-activists can help stave off its most dire consequences.