It is the uncouth phrase of mid-level managers and meddling consultants: “Let’s pick the low-hanging fruit.” OK, sure, whatever you say boss.

But unless you live on an orchard, your encounters with real low-hanging fruit don’t actually come too often. Low-hanging fruit seem to be everywhere, and really nowhere at all.

Should you use a metaphorical phrase without fully considering the literal specimens themselves or understanding the depths of its meaning?

While standard-size apple trees may have offered the lowest hanging fruits of yore, now, most likely, the lowest fruit of all is in dwarfed apple orchards.

The seeds of this question were planted a couple of months ago within the confines of our senior editor’s office, a space we often repair to in the afternoons to discuss media and other miscellany that would never reach a formal staff editorial meeting. Around that time, the Awl had published the personal account of man who claimed to have not consumed fruit for the first 26 years of his life. We were incredulous, but nonetheless intrigued. We were discussing this when we noticed an unidentifiable citrus fruit lying on the shelf of Ryan O’Hanlon’s bookcase. It was too small to be an orange and too round to be a lemon, Nick Jackson, our digital director, remembers. Its hue was strange as well.

Fruit was on the shelf, fruit was also on the Internet, and it was certainly on the mind. It was a near-perfect confluence of events. And then, as if a ripened apple fell from the sky, it happened. A Newtonian moment, if there ever was one. “What is the lowest hanging fruit?” There were chuckles. No one knew.

Of all the low-hanging fruit in the world, is there one variety that hangs the lowest? Is there a fruit out there, so low and so easy to pick, that it should take on some kind of ultimate idiomatic credence?

It seems like a simple enough query, but would there be a simple answer? And how might we even frame the question or judge the result? Is it in measurement from a human’s reach or the ground? Are bush fruits fair game? Does low-hanging fruit just pertain to the lowest individual fruit on a single tree? We’d need to call in experts. In exploring the physical truths, we might learn something about what the metaphor really means.

I promised my colleagues I’d set forth on this curious intellectual quest. And now, I think, I have settled upon a complicated, but very fruitful, conclusion.

IT BECAME QUICKLY APPARENT that this effort would not bear low-hanging fruit.

I contacted eight prominent pomologists. Perhaps somewhat flummoxed by the absurdity or cheekiness of the inquiry, only two responded. But they both had similar conclusions.

According to preeminent fruit expert David Karp, a researcher at University of California-Riverside who’s so knowledgeable about fruit varieties and distinguished in locating new ones that he’s been referred to by the New Yorker as “The Fruit Detective,” there are three ways to define fruit: botanically, culinarily, and horticulturally. Selecting which lens we use for the search would be crucial.

Botanically wouldn’t be the right one because much of what is classified as fruit in that area isn’t consumed by humans. “There’s things that squirrels eat that you and I wouldn’t eat, like acorns and stuff like that, right?” Karp says. The lowest of the botanical fruits are part of an extremely rare form of reproduction known as geocarpy, in which fruits grow or ripen underground. Of those, peanuts, actually, would be the most widely known. But culinarily, no one would ever consider peanuts fruit. And besides, they don’t really hang per se. However, the culinary perspective can muddy the precision of our search too. There are items in our supermarket aisles that are considered fruits that pomologists would scoff at. “I’m on the board of the American Pomological Society and when I featured some melons in our tasting, everybody looked down their nose at me,” Karp says. “‘Those are not melons; they’re actually classified with vegetables horticulturally.'”

Horticulturally is probably the way to go. If we reflect on the meaning of the phrase, it would make sense to consult the perspective of those who actually study the growth and harvesting of fruit.

What hangs lowest to the ground? Strawberries, Karp says. But there is a clear caveat here. “If you ever talk to a strawberry harvester, it’s known as the devil’s fruit because it’s hell to bend down—it really is back-breaking labor,” Karp cautions. And this is where the metaphorical begins to bleed into the literal. “It’s not ‘How low can you go?’ from the picker’s point of view in terms of convenience,” Karp adds. “It’s being at easy-to-grasp level, which depends on the height of the human but you know that would be like three to seven feet for your standard five-and-a-half or six-foot human.” And then, Karp begins to talk about the linguistic origins of the phrase. Low-hanging fruit, classically, was in reference to its position on a tree.

Of all the low-hanging fruit in the world, is there one variety that hangs the lowest? Is there a fruit out there, so low and so easy to pick, that it should take on some kind of ultimate idiomatic credence?

THAT SEEMS TRUE ON its face, but could it have another literal meaning we weren’t considering? This is more of a linguistic dilemma than a pomological one, so I turned to University of Pennsylvania linguist Mark Liberman, who has written about the origins of the phrase on his language blog. I asked him about the literal meaning, the metaphorical meaning, how the two might interact, and whether a human’s reach was the best variable to judge it by. Perhaps he would give me permission to solve the strawberry conundrum and reject the lowest-to-the-ground argument. He did, with some flare.

“I think that you might be over-thinking this,” Liberman says in an email.

“Fruit that hangs from the lower boughs of a tree is easy to pick, simply by reaching out and taking it,” he continued. “For fruit that’s higher up, you need to climb the tree, or use a ladder, or some other more difficult method. This applies to apples, pears, plums, and cherries, in my personal experience, and no doubt to peaches and other fruit trees as well.”

“So picking the low-hanging fruit,” he continues, “is an obvious metaphor for taking what comes easily to hand.”

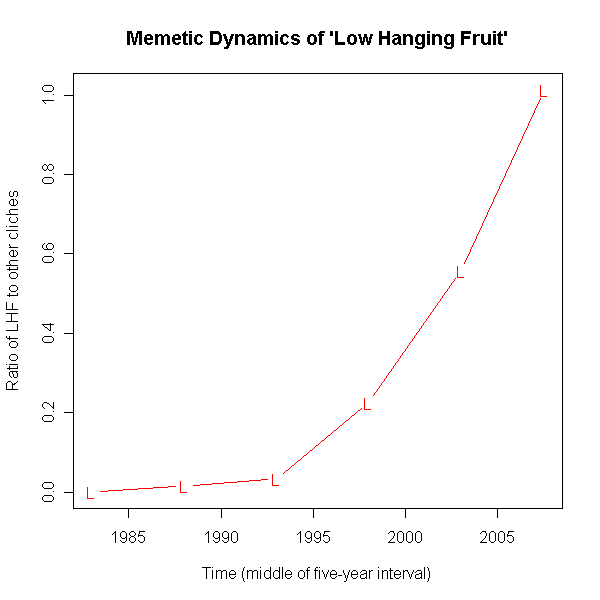

The metaphorical usage doesn’t appear to have a very long history, though. According to Liberman, the Oxford English Dictionary’s first partial reference is from a 1968 Guardian article: “His rare images are picked aptly, easily, like low-hanging fruit.” The first full-reference doesn’t come until 1972, in the form of materials published as part of a manufacturing productivity conference held by engineers. “We have plucked the low hanging fruit, so to speak, and have seized upon the somewhat obvious applications for keeping records and the like.” The New York Times didn’t use it until 1990. It didn’t really catch on until the mid-’90s.

(Chart: Mark Liberman)

“So the puzzle, I think,” Liberman says, “is why this phrase isn’t already in the bible and Homer and so on.”

That sounds like a complex linguistic mystery, but one for another day. Liberman provided me with what I needed: a special metric. It’s the fruit’s spatial relationship to the human hand, and the ease of its picking.

THE LOWEST OF THE low-hanging tree fruits have gone through some fairly major horticultural changes over the last 50 or so years. In older days, most orchards were filled with standard-size trees.

Desmond Layne, a professor of pomology that specializes in tree fruit research at Washington State University, explains in an email:

I am not an authority on the origin of historical expressions as it relates to fruit, but my suspicion is that this expression was coined some time ago, at a time when fruit were grown on large, tall trees and most of the fruit were picked by ladder (old time “Red Delicious” tree on “seedling” rootstock, for example). Obviously, the low-hanging fruit could have been picked by a pedestrian and [would not require] a ladder. Tall fruit trees were a common sight around the world more than 50 years ago. Even in Washington, today, some tree fruits–especially older pear trees, some sweet cherries, and even older apple orchards, may have trees that are quite tall and large and spaced far apart from each other. Because of the height of the average worker (less than six feet) and the height of the mature tree (maybe 12 feet or more), only a portion of the fruit on the tree can be picked from the ground.

But people were falling out of trees. And it takes much more time to climb in and out of a tree to pick the higher fruit than it does to just simply pluck it as you walk by. So orchardists began devising ways to eliminate high labor and insurance costs by making all of the fruit lower. “You’ll get more production from the whole orchard of full-grown avocado trees, some of which are 50 feet tall, even though there are many fewer trees,” Karp says. “But it costs you so much to harvest them and there’s so much of a danger there: Every once in a while somebody falls off and then that ends up costing you, the grower, one way or the other through insurance or whatever, that people are planting dwarfed orchards.” Taller orchards may also create significant business hurdles. “There may even be insurance companies that say we won’t even cover you for that,” Karp adds. So they genetically selected the trees to make them shorter. While standard-size apple trees may have offered the lowest hanging fruits of yore, now, most likely, the lowest fruit of all is in dwarfed apple orchards. In a way, the new generation of lowest hanging fruit was created by taking advantage of metaphorical low-hanging fruit. It’s a layered cycle that seems to somehow collapse in on itself if you give it too much thought, as Liberman suggested I was doing.

The ladderless pedestrian apple orchard was born and is now in vogue, even despite the loss in yield.

While some forms of citrus may have lower fruit because of drooping branches, they are often trimmed as part of a process known as skirting. Like strawberries, Karp notes, it’s not very easy to pick. “You wouldn’t want anything that’s one foot off the ground because then you’re stooping 1,500 times a day,” Karp says. Additionally, mold can develop on the fruit. “Also, snails, which can be a real problem,” he says, “can crawl up them and cause havoc in the tree by eating the leaves or what the hell—leaving slime on the fruit.”

Orchardists have been able to keep apple trees at about six or seven feet. The fruit height probably ranges somewhere between one and seven feet, around the optimal distance for an average picker. And they’re developing dwarfed rootstocks for other types of fruits. “It’s a multi-decade process to develop a dwarfing rootstock,” Karp says.

The phrase does, at least from Karp’s view, have some relevance in commercial horticulture.

“Specifically, as I’ve been saying, orchardists, in order to save on labor and time, which is money, have prioritized having accessible fruit,” Karp says. “Not low-hanging. Nobody gives a shit whether it’s the lowest fruit in the tree,” he chuckles. “That’s, commercially, an insignificant consideration. They just want it to be easy to reach and harvest.”

Here’s how the pedestrian apple orchard operates, according to Layne:

The trees are smaller, more compact and narrow, and they take up much less space. In fact, some orchards are now planted with more than 2,000 trees per acre and the trees are trained to a post and wire trellis (similar to grapes in a vineyard). Many commercial orchards are planting trees to higher density on very dwarfing rootstocks so that they can have high yields in the early life of the orchard, high sustained yields throughout the life of the orchard, and more easy orchard operations (pruning, thinning, harvesting, etc.). Some farms are using self-propelled platforms that drive down between the tree rows and orchard workers ride on the platform and work off both sides to prune, thin and pick fruit off the trees without using ladders. It is quite common in Italy now. This reduces labor costs and the possibility of injury that can occur if people fall off ladders.

WITH SPECIAL SIGNIFICANCE FOR the metaphorical meaning of the phrase, the lowest hanging fruits on the bigger trees aren’t always the best or most rewarding picks. “Given the more spherical shape of old style, large trees, the fruit that are most exposed to the sun are those in the outer portion of the canopy toward the top of the tree,” Layne says. “More sun exposure to the fruit and nearby leaves helps to ensure that those fruit are full of carbohydrates and other compounds that contribute to size, sweetness, and flavor. Often, in these big trees, the fruit in the lower canopy are smaller and of inferior quality. In such a case, the ‘low hanging fruit’ would not necessarily be the most delicious, even if they were the most accessible from the ground.” But, like everything else, dwarfed stocks have changed that, too. “In a modern, high-density orchard where the trees are smaller, shorter, and trained to wires, the canopies are narrow and the fruit are well exposed to the sun all the way down to the lower part of the tree, all of the fruit may be of similar quality with less difference in size, color, sweetness, etc.,” Layne explains.

So if the literal lowest hanging fruit in the world, apples on dwarfed rootstocks that you pick by sitting on a platform that races by, also tastes delicious, does that take away from the meaning of the metaphorical phrase? Aren’t more challenging and lofty tasks, the ones above the low-hanging stuff, supposed to be more satisfying and beneficial?

“Here’s another question,” Karp says. “What is the highest hanging fruit in the world? I have never considered that question in my pomological career.”

It could be the avocado, which resides in “big, old, and spooky” trees that look like a “monkey jungle” out of The Wizard of Oz. Then again, it’s probably the date, a fruit Karp once inspected after climbing 50 feet up a tree in California’s Coachella Valley. The trees can grow as tall as 90 feet.

More likely, though, it’s a nut that grows somewhere in the rainswept upper reaches of a tree in the Brazilian Amazon.

As with most things in life, it all depends on how you frame the meaning of the question.