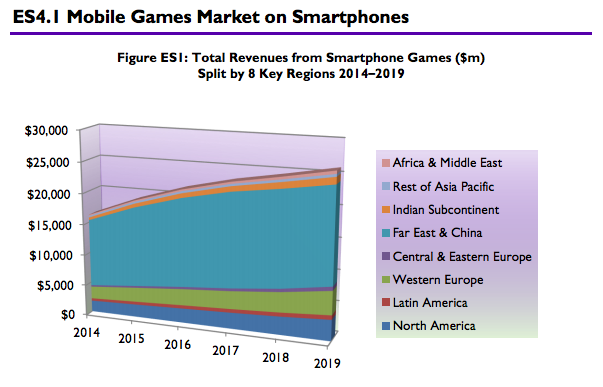

All those people staring down at their phones while stuck in cars, sitting on the subway, lounging in parks, or getting quick hits of workday distraction? They’re not just catapulting angry birds or crushing candy. They’re contributing to a lively economy of mobile gaming, where each app download or purchase of a few extra lives in-game is contributing to a $20.9 billion global market in 2014, according to a new report from Juniper Research. And this virtual economy—where large amounts of real money are traded for digital goods that have no use in the real world—is only getting bigger.

Juniper Research, a decade-old British research firm specializing in mobile commerce that has worked with clients including Apple and IBM, predicts that the mobile gaming market will grow to over $40 billion by 2019. These big numbers might prompt a question: Why are we paying so much money for things that don’t actually exist? I previously wrote about the economies of online video games like World of Warcraft and EVE, where digital goods are sold for real money among players. But over the past year millions more people have begun participating in virtual economies through their smartphones, and a new branch of economics is growing out of those users.

The economy of the future will be as digital as possible, increasingly non-Western, and contained within easily accessible smartphone ecosystems.

A new book from MIT Press, Virtual Economies: Design and Analysis, by economists Vili Lehdonvirta and Edward Castronova, is an informative and surprisingly entertaining primer on these new markets. Every economy is based on “scarce means,” they write, or a discrepancy between supply and demand. It’s easy to see how that might function with a resource like gold—there is always less available than participants in the economy might want. But in a digital space, where objects are made up of infinitely replicable combinations of ones and zeroes, scarcity is harder to define. But it’s precisely this scarcity, Lehdonvirta and Castronova argue, that makes virtual economies function, and indeed boom to billions of dollars.

Screennames for the popular messaging service ICQ, which were numbered according to when users signed up, provided one early example of a virtual economy in the 1990s. Early users received five-digit-long names, while late-adopters went all the way up to nine digits. As the service grew, names were bought and sold, with catchy signatures like 11111111 netting up to $3,000. A five-digit name was rare, and thus valuable. “Like a vanity car license plate … it made its owner stand out,” the authors write.

Virtual economies have gone mainstream since then, expanding to encompass everything from digital stickers purchased on Facebook to the Apple app store, an “open virtual economy” where “any third-party developer could come and sell virtual offerings,” according to Lehdonvirta and Castronova.

Those virtual offerings often take the form of “content”—“artificially scarce resources … that create challenge and competition,” as defined by Virtual Economies, within games. If you’ve ever paid for new levels of Angry Birds, you’ve participated in the virtual content economy. Designing content gives merchants a unique advantage in the digital ecosystem: They can make supply exactly fit demand at all levels of their market, thus optimizing profits. So rather than charging a flat fee for subscriptions, they can price different content packages higher or lower, drawing in money from both casual players and committed addicts.

(Chart: Juniper Research)

This model can also explain the different content structures of games over time. A high-end “triple-A” game like Halo offers lots of content immediately, with fans paying a premium for access. Online role-playing games like World of Warcraft consistently release or update content over time, trailing off once the game passes into irrelevance and subscribers lose interest. But free-to-play games that target diverse customers by charging for small packages of added content have a much longer tail—new content is often created long after the game’s release. It’s like a slow drip of morphine rather than a single injection of heroine—it might not produce as much of a bang, but it’ll probably keep you hooked and paying longer.

As more services and media move to an online-only format—think books, movies, and shopping experiences—the systems pioneered by gaming’s virtual economies will doubtless trickle into other facets of our lives as consumers. Whether we play video games or not, we’ll soon be dealing with the consequences of their economics.

WHILE LEHDONVIRTA AND CASTRONOVA give an intimate look at how virtual economies are constructed, the takeaways of the Juniper Research report show what the future of digital markets might look like, with video games as the frontrunner of change.

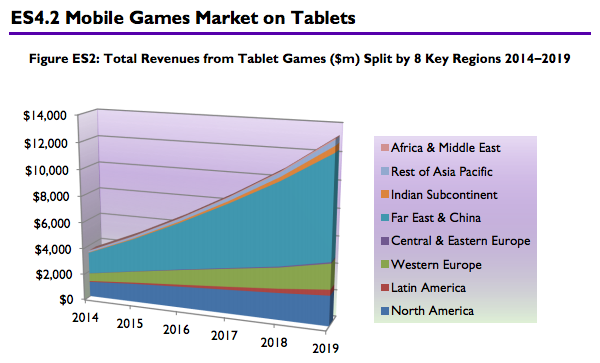

(Chart: Juniper Research)

For all of its social-network start-ups, North America falls far behind other areas of the world in mobile-gaming revenues. Asia is home to the vast majority of mobile gaming payments, with $10 billion in 2014, over four times as much volume as North America. North America and Western Europe have similarly sized mobile gaming economies—around $2 billion—while India, Latin America, and Africa are clustered at the bottom. Of these, the African and Indian markets in particular are slated to grow quickly—an easy bet, given the regions’ ready adoption of mobile banking technology.

The report also suggests that the tablet gaming market will boom, while the markets for games on portable video game systems—purpose-built devices like the Nintendo 3DS rather than smartphones with games added to other functions—will actually contract up to 22 percent over the next seven years.

Taken together, Virtual Economies and the mobile gaming report give a roadmap to how we will consume digital content over the next decade. This economy of the future will be as digital as possible, increasingly non-Western, and contained within easily accessible smartphone ecosystems. Its merchants will rigorously mete out content over time to keep customers engaged and the money flowing. While we might not be paying for digital-only groceries instead of actual produce any time soon, all economies will soon be, to some extent, virtual.