Denver’s International Airport (1985-1995)

In 1985, Denver announced a $1.5 billion plan to annex a site 24 miles away to create a replacement for aging Stapleton Airport. Tough times in the airline industry led one local carrier, People’s Express, to cease flying and the parent company of another, Continental, to declare bankruptcy. The remaining airline with a hub at the airport, United, used its leverage to obtain concessions from the city, including a $200 million maintenance hangar. To keep United from having an unfair competitive advantage, Denver installed an automated baggage handling system for $461 million; it never worked properly. Total costs reached about $5 billion. As construction neared completion, the airport revised travel demand forecasts down, and first-year boardings declined compared to the previous year at Stapleton. After Continental effectively stopped flying, United was able to set extremely high fares, making the airport profitable — at considerable consumer cost.

English Channel Tunnel (1985-1994)

After 200 years of on-and-off discussion, the governments of England and France finally put out a call for proposals in 1985. The winning bid estimated costs at £4.74 billion. During construction, the winner of the cross-channel design competition, Eurotunnel, updated that number to £8 billion, with the final price of £9.5 billion on completion in 1994. During the process, Eurotunnel continued to increase future sales estimates without clear justification; actual 2003 revenue of £584 million would be less than half the projected figure. A cost-benefit analysis by transportation researcher Ricard Anguera for the U.K.’s Strategic Rail Authority argues that the British economy would have been better off if the Chunnel had never been constructed.

Boston’s Central Artery/Tunnel Project, aka “The Big Dig,” (1983-Present)

Boston’s elevated Central Artery highway carried almost 200,000 vehicles through eight daily hours of bumper-to-bumper traffic. Something had to be done. After much haggling, city and state leaders settled on a plan that included an eight-lane underground highway tunnel and then lobbied Congress, with the help of then-Speaker of the House Thomas P. “Tip” O’Neill Jr., for funding. Costs ballooned from $3.7 billion (2002 dollars) to $14.6 billion, and one woman died when a poorly built ceiling collapsed in 2006. Bechtel/Parsons Brinckerhoff and two other design and construction firms eventually agreed to pay a $458 million settlement as restitution and punishment for problems ranging from leaks to faulty wiring. In March, contractor McCourt Construction Co. separately pled guilty to conspiracy to defraud the government with $300,000 in overcharges.

Seattle’s Sound Transit Link Light Rail (1996-Present)

In 1996, Seattle proposed a $1.67 billion light rail line from the University of Washington down to Seattle-Tacoma International Airport, to be opened in 2006. By 2000, before construction had even begun, cost estimates ballooned to more than $4 billion, and Sound Transit pledged to scale back. The next year, the U.S. Department of Transportation inspector general advised Congress to hold back funding for the project due to overruns. Along the way, several Sound Transit executives resigned, and State Transportation Secretary Douglas MacDonald revamped the state’s cost estimating system. In late 2001, all three Seattle mayoral candidates endorsed vague plans for a monorail, later killed. In 2007, Sound Transit tried to pass an $18 billion proposition to extend the light rail. It failed. Two stages, covering about 16 miles from downtown Seattle to the airport, are now scheduled for completion late next year at a cost of $2.4 billion. An extension to the university, planned for 2016, will cost $1.7 billion more.

Miami’s Metrorail Expansion (2002-Present)

Miami-Dade County put a ballot measure before the voters in 2002, promising 88.9 miles of new Metrorail as part of the “People’s Transportation Plan” paid for with a half-percent sales tax increase. It passed. Since then, the county has spent more than half the tax revenue of $800 million on routine operations, maintenance and 1,000 new transit jobs, according to a June investigation by The Miami Herald. A $555 million estimate for rail expansion tripled to $1.6 billion, and Metrorail now runs fewer trains than it did in 2002. But $2 million of the tax revenue did buy something tangible: office furniture for agency headquarters. Political consultant Ric Katz, a leader of the campaign in favor of the transit ballot measure, told the Herald the rail plan was a “fairy tale.”

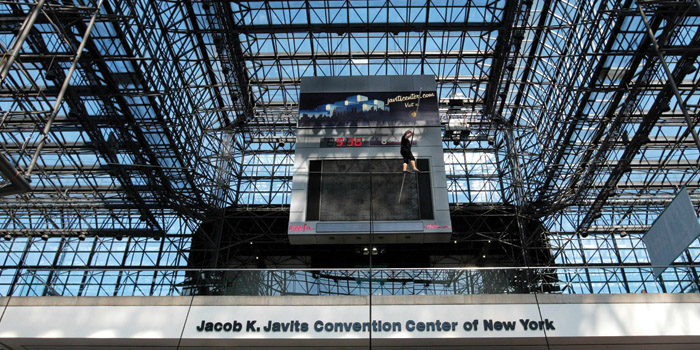

New York’s Jacob K. Javits Convention Center (1969-1986)

When Big Apple leaders began work on what would become the Javits Center, they hoped the massive conference hall would be a boon for business tourism and the lynchpin of economic development in Hell’s Kitchen (later renamed “Clinton” by realtors). Instead it cost $486 million, 30 percent more than projected, at least partly due to Mafia bid-rigging. Anthony Salerno andVincent DiNapoli of S&A Concrete, which won an overpriced $30 million concrete-pouring contract, were eventually convicted on federal racketeering charges linked to Javits and 15 other New York projects. As far as visitors, the center didn’t live up to expectations, as conventions drew a mostly local crowd, with area hotels averaging fewer than 0.2 room-nights per attendee. During the late 1990s, Gov. George Pataki unveiled a plan to double Javits’ size. This January, after projected costs increased 100 percent to $3.2 billion and the city and state had spent $100 million on development, then-Gov. Eliot Spitzer killed it.

Sydney Opera House (1957-1974)

Estimated cost/completion date as of January 1957: $7.2 million AUD/January 1963. Actual cost/completion date: $102 million AUD/October 1973. Need we say more?

Bay Area Rapid Transit (1951-1974)

In 1953, the Bay Area Rapid Transit District hired the New York engineering firm of Parsons, Brinckerhoff, Hall and Macdonald to conduct a feasibility study of a rail transit system. To deal with increasing population and congestion, Parsons proposed a 123-mile system around the Bay Area, estimating a cost range from $586 million to $716 million. “We do not doubt that the Bay Area citizens can afford rapid transit: We question seriously whether they can afford not to have it,” its report concluded. Voters passed a $500 million bond issue, with Bay Bridge tolls to cover the rest, but the detailed design completed in 1961 — that is, just two years later — estimated the cost would be $1.3 billion. San Mateo County and Marin County dropped out, and the system shrank by half to 71 miles. Yet when it went fully operational in October 1974, the price had jumped to $1.6 billion. By the late ’70s, per-passenger costs were double those of buses, and BART was contributing to mounting deficits in other local transit systems.

Sources: Bay Area Rapid Transit District; The Boston Globe; P. Anthony Brinkman, MegaProjects; EuroTunnel; Fortune; Peter Hall, Great Planning Disasters; Javits Center; Massachusetts Turnpike Authority; The Miami Herald; The New York Post; The New York Times; Heywood Sanders; Seattle Post-Intelligencer; The Seattle Times; Sound Transit; Strategic Rail Authority U.K.

Photo Credits: ZumaPhotos/Newscom (Chunnel, BART); Andy Dickerman/ Providence Journal/ KRTPhoto/ Newscom (“Big Dig”); Seattle Sound Transit Photo Pool (Seattle); Miami-Dade County Metrorail (Miami); AFP Photo/Matt Campbell/Newscom (Javits); SCUPhotos/Newscom (Sydney)

Sign up for our free e-newsletter.

Are you on Facebook? Click here to become our fan.