In September of 2015, Gary Berthelot was working on a restoration project for a restaurant in Kiln, Mississippi, that had been damaged during Hurricane Isaac a few years prior. Berthelot, 54 at the time, owned his own construction business and had been working as a general contractor for over 30 years; this job should have been much like any other. But things went horribly awry when Berthelot and the other crew were pouring concrete on the flooring of a raised deck. A section of the flooring collapsed. Other workers at the site tried to rescue Berthelot, but his injuries were too serious, the local chief deputy told the Associated Press. Berthelot left behind a wife, four children, and four grandchildren.

Six months later, a rash of news organizations in the region, including the Sun Herald paper and ABC and Fox affiliates, produced stories about Berthelot’s death. All of them cited the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, a relatively small federal agency whose mission is “to assure safe and healthful working conditions for working men and women.”

By the time of the news reports, OSHA officials had investigated the accident and decided that Berthelot and another construction company working on the restaurant, Great Southern Building Systems, were using plans they should have known wouldn’t support the weight of a concrete floor. Three Great Southern employees were laboring alongside Berthelot during the collapse, but they managed to escape in time. OSHA officials thought Great Southern “failed in its responsibility to protect its employees” and that Berthelot’s death “could have been prevented”—and they published a press release saying so, with the very hopes that local news stations would pick it up. Local journalists obliged within days.

“Our job is to do everything we can to encourage employers to prevent workers from being injured,” says David Michaels, who became the head of OSHA in December of 2009. OSHA has the authority to use educational programs, fines, prosecution, and more to get companies to comply with national worker-safety laws. “Using the press is an important tool that OSHA really hadn’t embraced before we got there,” Michaels says. In the first six months of 2009, OSHA was putting out an average of 13 press releases a month about enforcement. By the first six months of 2016, that number had risen to 44.

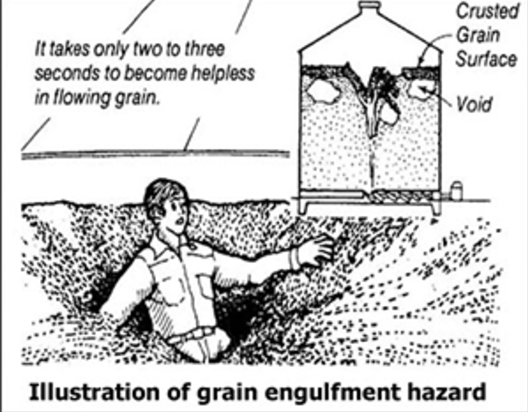

In fact, Michaels’ OSHA eventually became infamous—especially in construction, manufacturing, agriculture, and other industries that put workers at risk of immediate physical danger—for its press releases. The releases got out the information quickly whenever OSHA cited a company for safety violations, whether it was unstable trenches or unguarded band saws or wobbly piles of grain large enough to suffocate. The releases were often colorful and compelling, with stern quotes from OSHA officials and details such as whether workers killed on the job had children, like Berthelot did. They highlighted more minor violations than the agency used to call attention to, during the Bush administration. And, employers fretted, they could quickly rise to the top of search-engine results for a company’s name.

“It was obviously to publicly shame employers,” says Robert Box, principal consultant for Safety First, a firm that helps companies make sure they’re OSHA compliant. “I think that had a lot of employers running scared.”

Michaels, an Obama administration appointee, stepped down, as expected, in January of 2017, when Donald Trump assumed the presidency. Since Michaels’ resignation, OSHA has published markedly fewer press releases about enforcement actions like the citations the agency issued against Great Southern. In the first six months of 2017, OSHA published 29 press releases about enforcement, 18 of which are dated before the inauguration on January 20th, compared to 263 in January to June of last year. Michaels’ spot—as well as that of OSHA’s chief of staff and senior advisors—remains empty.

(Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

What does the apparent change in press release policy mean for American workers? One recent study suggests the prospect isn’t good. Every OSHA press release leads to fewer injuries and to 73 percent fewer safety violations by nearby companies in the same industry, Duke University economist Matthew Johnson found in research he has submitted for peer review. Although Johnson didn’t study what would happen if OSHA halted its press release strategy, he was willing to “extrapolate” from his findings that “injuries might increase if this policy goes away.” (Johnson is less comfortable speculating on any increase in deaths. The way he conducted his study, deaths and hospitalizations were rolled into one measure.)

Johnson’s research supports the thinking behind OSHA’s old media strategy, which started just months after President Barack Obama took office, even before Michaels’ arrival. To explain, Michaels rattled off some statistics. OSHA is supposed to oversee the safety of 130 million Americans at more than eight million workplaces—most of the private companies in the United States, in fact. Yet the agency only has about 2,100 inspectors, who do about 40,000 inspections a year. “You can’t count on inspections alone to change employer behavior,” Michaels says. “We said, ‘If we start issuing press releases, employers will remember OSHA is on the job and they have the chance of being inspected.'”

“The point was to encourage employers who we weren’t inspecting to abate hazards before workers get hurt and before OSHA inspects,” he says.

(Illustration: Occupational Safety and Health Administration)

It’s unclear why press releases have declined so much with the new administration. Press officers now working with the Department of Labor, OSHA’s parent agency, didn’t return requests for comment. “In all likelihood, they’re doing the same amount of enforcement, [but] doing less press releases,” says Jesse Lawder, who worked as a Department of Labor spokesman for much of the Obama administration. OSHA’s budget determines how much inspecting and citing field officers do, not their leaders’ philosophies, Lawder says.

Employers have certainly noticed the change. “Yeah, it’s a dramatic drop-off,” Box says when I first ask about OSHA releases. “The new administration wants to go on a different route. It’s more along the lines of assistance, free training opportunities with regards to safety and health, partnerships established between different agencies and employers, things of that nature.”

“More of a carrot than a stick,” he says.

Companies have “welcomed” the change, Box explains, because they thought Michaels’ press releases were unfair. OSHA would publish them immediately after officials cited companies for unsafe practices, but before the companies had a chance to contest the charges. It’s possible that the companies in the releases later negotiated down their citations and fines. Supporters of the policy counter that it’s standard practice—at the Department of Justice, for example—to put out press releases when the feds file a complaint, but before the issue has been decided on. “It is standard process,” says University of Maryland law professor Rena Steinzor. “It would be a change to stop doing it.”

No one ever complained that OSHA press releases didn’t work as intended, Michaels says. And even Box agrees that they were effective: “It had a lot of employers talking about it amongst each other about the new, aggressive OSHA and maybe that was the trigger to get them to spend a little bit more time and effort on the safety programs,” he says.

Whether carrots will work as well as sticks remains to be seen.