At a certain point, emergent technologies become part of the kitchen-table dialogue, no longer the domain of wacky environmentalists or trendy technophiles.

The electric car may be at that juncture today.

Or maybe it was Thursday, when the United Kingdom announced subsidies of up to $7,500 to get Britons in electric cars — a boost for automakers and a sop, or sop-up, to greenhouse gas fears.

In the larger car market of America, President Barack Obama touted the cars during his campaign; he pledged to get 1 million plug-in hybrids on the road by 2015, which is not so far away. So far, his actions have been as good as his word, but whether it’s doable or not is another question. The Electric Drive Transportation Association has said it will only happen with a coordinated set of policies and technology advances, and has released a set of policy recommendations.

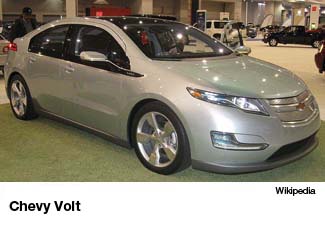

The Obama-supported stimulus bill does provide significant incentives for the electric car-buying public, with estimated tax credits ranging from the familiar $7,500 for the Chevy Volt to $1,200 for the three-wheel Zap Xebra. Previous credits would have stopped after 250,000 vehicles had been sold across the whole industry. Now, the credits will apply on up to 200,000 vehicles from any single manufacturer.

But subsidies may not be the only financial reward. A few months ago Miller-McCune.com interviewed Jonathan Dorn, a policy wonk with a sweet tooth for electric cars. “The real economic benefit has to do with looking at what the consumer would have to pay to move the vehicle,” he said. “The cost to charge an electric vehicle and drive it for 30 miles is 73 cents. The latest comparable price data (July 2008) shows the cost to travel roughly 30 miles on a gallon of gasoline was $3.91, and (it was) $2.51 for natural gas. Even though gasoline prices have dropped dramatically over the last few months, the decrease will be short-lived.”

Still, there seems to be a disconnect between political will and bureaucratic action. Two months ago The New York Times reported that a $25 billion loan program — established in 2007 — to promote electric cars had not been touched. The director explained that they were still evaluating loan applications in late February, no doubt with several politicians pounding on their door. Energy Secretary Steven Chu was quoted as saying that the first loans would be made by late April or early May.

Chu will get another $2 billion from the stimulus package designated for development of the advanced battery technology needed to power electric cars.

Several hybrid gas/electric vehicles such as the Volt are being designed to go about 40 miles on a charge, with gasoline used to drive a generator to provide electric power after the initial charge has been expended.

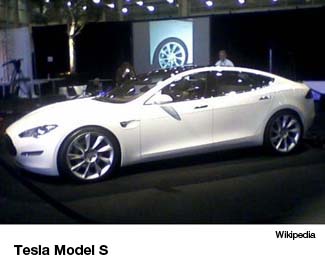

But the hybrid electric may soon be old news. Tesla Motors recently announced production of an all-electric vehicle that it says will go 300 miles on a charge. The company, which sold 300 of its two-door Roadster electric sports cars ($109,000) last year and has a 1,000-name waiting list for that car, announced in March that it is taking orders for its Model S sedan.

The Model S is being touted as the “first mass-produced, motorway-capable electric car.” It’s anticipated the base price will be $49,900 after a tax credit of $7,500. (The Volt, due on showroom floors next year, will likely cost around $30,000 after the credit.) Tesla says the Model S will carry its own recharger, can recharge in 45 minutes, and will be moving off the assembly line in 2011. Company executives have been reported to be confident they will receive $350 million from that $25 billion loan program.

Batteries have always been the sticking point for electrics; the time needed to recharge is at the crux of the electric car’s practicality. A recent discovery by Massachusetts Institute of Technology researchers could provide the breakthrough electric car manufacturers have been looking for.

Scientists have long believed the lithium ions and electrons in the rechargeable batteries in use today move sluggishly through the material, resulting in relatively slow power rates and long recharge times. But research shows that lithium ions move very quickly when its surface structure is placed outside the cell, like a beltway around a city, rather than in the traditional tunnel formation. The MIT team dubbed this new configuration the “beltway battery” and have found the process will recharge a small cell in 10 to 20 seconds versus six minutes for a cell made in the traditional way.

The difference between minutes and hours means a lot to a traveler wanting to get back on the road. Gerbrand Ceder, the principal researcher for the study, said this design modification isn’t difficult and that beltway batteries could be in the marketplace in two to three years.

There are a couple of other indications the electric car may be powering its way into the mainstream. ExxonMobil Chemical is producing a commercial line of microporous films for lithium-ion batteries used in hybrid and electric vehicles. And Chinese leaders recently announced they have a plan to turn the country into a leader in producing hybrid and all-electric vehicles within three years.

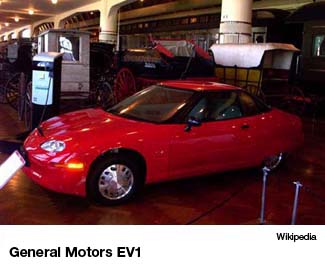

Electric-powered vehicles are not exactly new; the first electric carriage was devised by a Scottish inventor in the 1880s, and a few decades later a quarter of the cars in the United States were electric-powered. Skip forward a century, and in 1996 General Motors launched the EV1, an electric car that sold in California and Arizona for several years. In 2002, citing lack of demand, the company abruptly stopped making the EV1, and prompting that documentary cult classic Who Killed the Electric Car?

If it was dead once, it’s been reborn. There have always been proponents. A notable one is John Waylon, who races his retrofitted ’72 Datsun, souped up with a load of batteries, and wins time after time. He even beat a Corvette. Hands down.

Sign up for our free e-newsletter.

Are you on Facebook? Become our fan.