The idea of having lots of average people collect data for Certified Important Research TM is a hot topic in science circles. Probably the best known example of crowdsourced citizen science is the venerable (since 1999) SETI@Home, in which your home computer gets looped into a network and merrily helps analyze radio telescope data that might help locate extraterrestrial intelligence.

But beyond bragging rights when E.T. does finally phone, SETI@Home isn’t terribly interactive. Another example that is also one of the oldest is the Audubon Society’s 112-year-old Christmas Bird Count, in which volunteer birdwatchers scan their local skies, counting and categorizing what they observe to create a mosaic State of the Avian Union for the world. (The obverse of that is the Coastal Observation and Seabird Survey Teamcreated by Julia Parrish at the University of Washington, which counts dead birds.)

About two months ago a new crowdsourcing effort started to get some buzz: ZomBeeWatch!

The effort is more like the Audubon effort than SETI, in that it requires live humans to look for bees acting strangely, explains John Hafernik, the biologist behind the effort. Honeybees are having a hard enough time as it is, what with “colony collapse disorder” devastating hives in North America and Europe. Hafernik accidentally discovered a new threat to bees just outside the doors of his lab at San Francisco State’s Hensill Hall.

He happened to need some food for some praying mantises he was studying, and there happened to be a bunch of dead bees laying around on the concrete that had apparently expired there overnight. He brought them into the lab and by luck watched as a maggot started emerging – “sort of an analog to Alien,” Hafernik conceded—from one of the corpses. That maggot didn’t spring from a known bee parasite, but it did spring from a very well-known native fly (Apocephalus borealis for those playing at home) which usually victimizes solitary bumble bees and certain wasps.

Normally, this would be great news—a native species is wiping out an invasive one.

But much like Volkswagens and Heinekens, we like honeybees, which also are an import from Europe. More importantly, we need bees to pollinate most of our crops, which are also often imports.

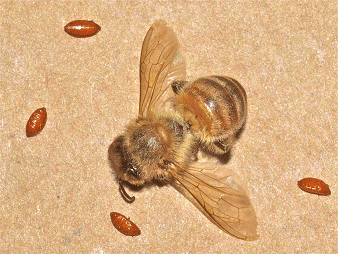

A ZomBee and four pupae from the parasitic fly. (Photo from ZomBeeWatch.org)

Hafernik and his colleagues started examining this bee-fly link, and soon learned the bees had been drawn to the light outside the lab door there at night and wandered around—even in the cold and rain—until they finally laid down and died, which is not an approved activity for this very regimented bug. The scientists dubbed these disoriented critters “ZomBees,” proving once and for all that scientific endeavor need not derail a promising career in marketing. They’re not sure exactly how the bees’ controls are hijacked, but they’re sure it’s related to the flies.

So how much of a threat are these common flies to the honeybees, which do about $15 billion in free labor in the U.S. alone each year? To determine how close we are to micro-geddon, Hafernik first needed to know how common it was for flies elsewhere to have discovered a tasty new host for their eggs, and so ZomBeeWatch was born.

There are many ways you can get involved. It can be as easy as collecting honey bees that are under your porch light in the morning, under a street light or stranded on sidewalks. If you are a beekeeper, setting up a light trap near one of your hives is the most effective way to detect ZomBees. It’s easy to make a simple, inexpensive light trap from materials available at your local hardware store. To test for the presence of Zombie Fly infection all you need to do is put honey bees you collect in a container and observe them periodically. Infected honey bees give rise to brown pill-like fly pupae in about a week and to adult flies a few weeks later.

I met the genial Hafernik recently at a symposium in Denver, and at that time ZomBees had been reported as far north as Oregon and as far east as the Dakotas. A map on the website shows there have now been reports as far north as the Seattle area, although with winter approaching the spread may slow down as the bees hibernate. Maps on the group’s website show where citizen sampling is taking place. Bees are pretty thoroughly studied and these fly takeovers haven’t been witnessed before the Hensill Hall Incident of 2009, so the ZomBeeWatch team believes having a nation of observers keeping tabs on the spread is a genuine help.

Scanning the ground for dead bees may not be as challenging as it might be completing a game where you unfold proteins, but it’s still valuable and can even be fun. Plus, as the bird-collecting Parrish might say, it helps liberate science from the academy. And that’s good for scientists, citizens—and honeybees.