While the average human being probably doesn’t find the sight of a cockroach dashing through the kitchen at 1 a.m. anything short of disgusting, researchers at Oregon State think it’s inspiring. They are using the creature, a biological and engineering marvel, as “bioinspiration” for the world’s first legged robot that can run over rugged terrain.

An earlier Miller-McCune.com series on biomimicry explores five other inventions stolen from nature — from gecko-like adhesive to Lotusan exterior paint and sunflower-esque solar panels, but it appears that Mother Nature’s copycats are just getting started.

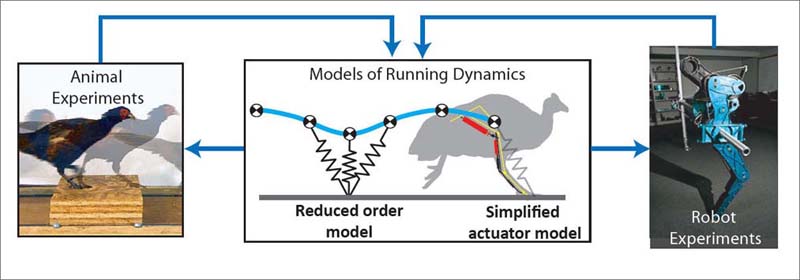

The National Science Foundation is funding Oregon State engineers who are studying cockroaches — and more charismatic animals like the guinea hen — to determine how they use energy in their legs to achieve running stability. The researchers hope first to discover how some track-star animals can run so effortlessly, and then to translate their findings into a robot that can run over rough terrain without using too much computing power.

John Schmitt, an assistant professor of dynamics and control at the university, says that, with certain limitations, cockroaches don’t even have to think about running — they “just do it” (perhaps Nike should enlist them for a commercial). Their muscle action is instinctive and doesn’t require reflex control, so the insects can react to changes in terrain or other obstacles faster than a nerve impulse can travel.

Although some walking robots have already been built, none of them are able to run as well as living, breathing animals. The robots that can walk require so much energy and computing power to do so that they are not very useful — an obstacle that would have to be overcome to create a truly effective running robot.

However, the cockroach’s ability to maintain its speed when hurdling blocks (it only slows down about 20 percent to go over blocks three times higher than its hips) indicates that its running stability is a result of its build and not its reaction time. The guinea hen can automatically adjust to an unexpected change in terrain as much as 40 percent of its hip height: the equivalent of an adult human running full speed into a 16-inch-hole and not missing a step.

In a computer model, the researchers have created a concept that would allow a running robot to recover from a change in ground surface — think large pothole — almost as well as a guinea hen.

Schmitt thinks that the running robots could serve a valuable role in military operations, law enforcement or space exploration, and the technology could also be used to improve prosthetic limbs.

But don’t worry, gold-medal aspirants: At least for now, they have their own Olympics.

Sign up for our free e-newsletter.

Are you on Facebook? Become our fan.

Follow us on Twitter.