Earlier this week, Politico reported on a fight brewing in Congress over the reauthorization of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program in the United States’ farm bill.

At issue is whether stricter work requirements should be imposed on certain SNAP recipients. Under SNAP’s current rules, children, the elderly and disabled, and adults with dependent children are exempt from work requirements; they receive, on average, $134 a month, although levels vary with income. Current rules also mandate that able-bodied adults without dependents (ABAWDs) who receive SNAP benefits for more than three months must work or participate in job-training or volunteer programs (which are not available in many parts of the country).

But states and counties can waive those requirements during times of high unemployment. And during the recession, a number of states and counties implemented exactly these kinds of waivers. Today, waivers remain in place in eight states and territories and in portions of an additional 28 states. While it’s not entirely clear what sort of changes congressional Republicans are considering, the Trump administration has signaled that targeting waivers is a priority.

In targeting these waivers, however, the administration is addressing a problem that seems to barely exist. Yesterday, the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a progressive think tank, published a report that offers some timely and useful additional context on the workforce status of SNAP recipients. To begin with, as the chart below (from the CBPP) illustrates, most SNAP recipients are children, elderly, or disabled. Non-disabled adults represent only 35 percent of SNAP recipients; ABAWDs represent just 13 percent of recipients:

The CBPP report is particularly useful thanks to its methodology, which differs a bit from simple assessments of SNAP recipients’ work status. Most analyses of SNAP recipients’ labor force participation look at a group of recipients in a given month to determine how many are working in that month. The CBPP report, however, goes a step further and looks at whether SNAP recipients in a given month have worked in the year before or after that month. This is an especially helpful metric given that many SNAP recipients work in the kind of low-wage jobs and industries that are often marked by instability and short tenures.

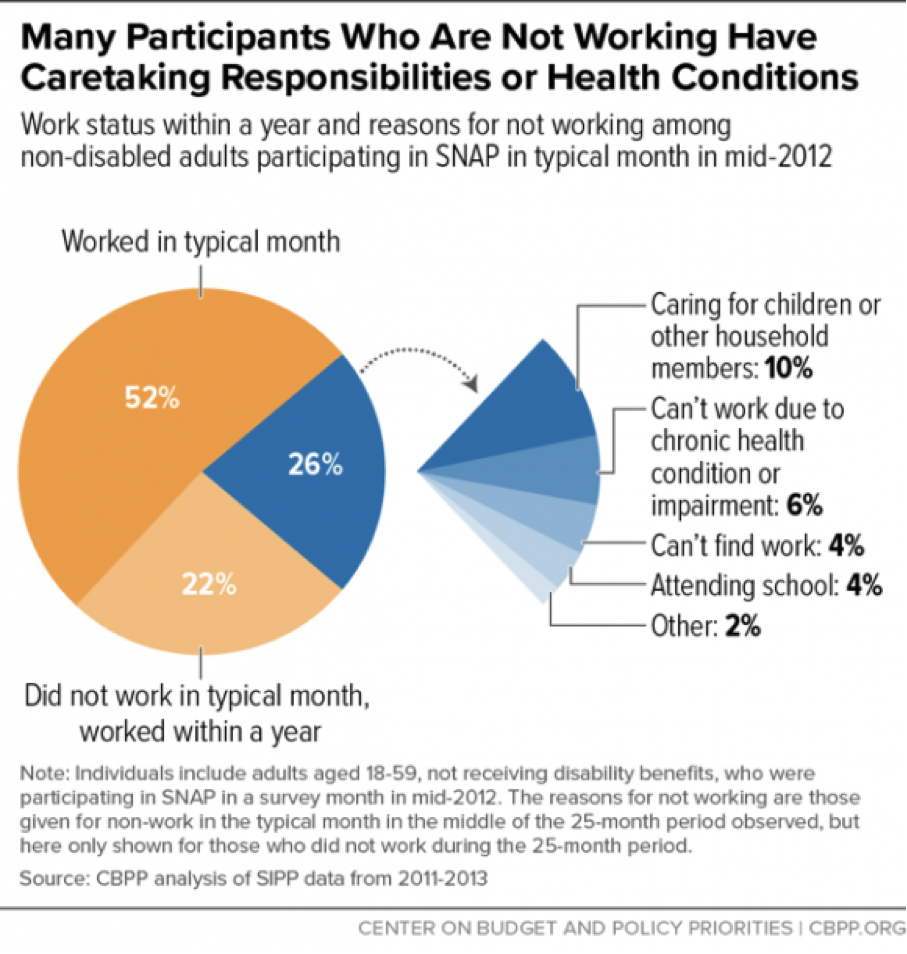

The majority (52 percent) of healthy adult SNAP recipients worked in a typical month, but an even higher percentage—74 percent—worked at some point in the year before or after the month they were surveyed. Meanwhile, 87 percent of SNAP households with children and a healthy adult reported participating in the labor force during the year before or after they were surveyed.

Meanwhile, among the 26 percent of SNAP recipients who didn’t report formal labor force participation in the year before or after they were surveyed, the overwhelming majority cited care-taking responsibilities, health issues, or being in school as reasons for not working.

The report concludes that the SNAP program is, by and large, functioning as a safety net program should. SNAP recipients are more likely to use the program when they’re not working, and the majority (64 percent) of recipients use the program for less than two years. Recipients who did access the program for longer periods of time were “no less likely to work while getting SNAP than other participants,” which suggests the benefits aren’t, in fact, disincentivizing work.

“The biggest takeaway we hope people get from the paper is that SNAP participants are already working when they can, just usually in the low-wage labor market, where jobs are often unstable because of shifting schedules and lack key benefits like paid sick leave,” writes researcher Brynne Keith-Jennings, one of the report’s authors, in an email. “A mother who is a waitress could lose food assistance simply because her employer didn’t provide her enough hours to meet a fixed weekly work requirement. Harsher rules around work for our nation’s most disadvantaged won’t do anything but make it harder for them to put food on the table.”