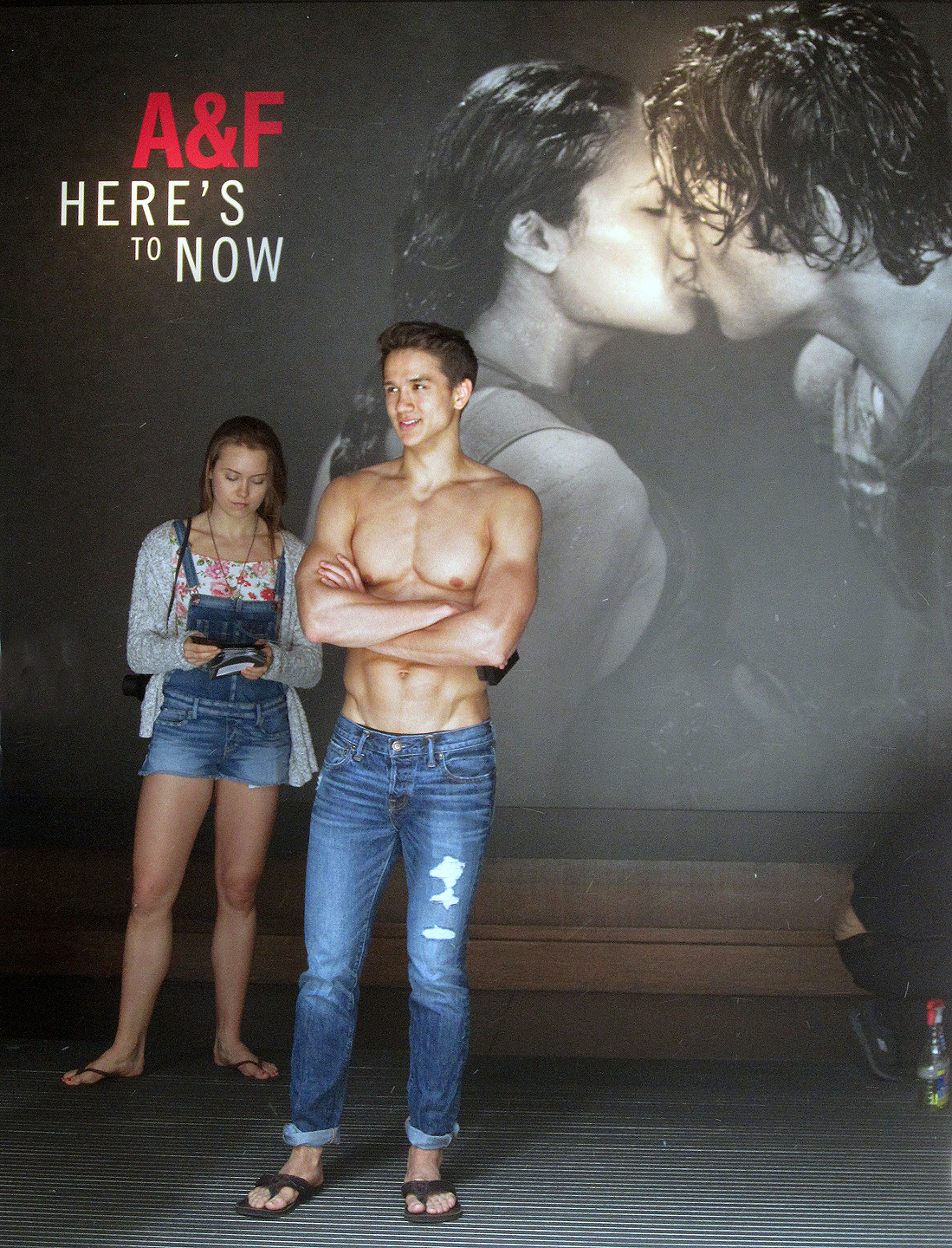

In the distant future, your local Abercrombie & Fitch might not look quite so … stimulating.

The clothing brand is loosening looks-based requirements for its sales staff and scaling back on its signature sexy marketing, the Associated Press reported last week. Abercrombie & Fitch recently posted 12 straight quarters of decline, which is a huge change in fortune for a brand that had been a teen tastemaker in the 1990s and early 2000s. But the company has weathered extreme change before. Founded in 1892 as a sporting goods store, in its first decades, Abercrombie & Fitch outfitted Teddy Roosevelt, Ernest Hemingway, and Charles Lindbergh with guns and fishing and camping gear. Its transformation in the 1990s under then-CEO Michael Jeffries is considered one of the greatest in retail history, as Salon reported in 2006.

Others have traced the history of the company in prose and pictures, but we recently realized another way to track its life course: patents. Throughout its lifespan, Abercrombie & Fitch has earned patents that closely reflect its evolving priorities, away from its specialized gear roots, to a certain image and lifestyle. It’s a strategy that’s common to many modern brands.

The effect of such marketing on modern-day life is enormous, as researchers documented during A&F’s own heyday. In 1999, Fortune reported that in one Maryland high school, the most popular students were called the “Abercrombie crew.” This was the first generation of American teens, journalist Lauren Goldstein noted, to actually name themselves after a brand, instead of just wearing it a lot. In 2000, activist Naomi Klein argued that brands were overtaking culture made by individuals and communities. “The problem with sponsored culture is that it indoctrinates everybody into the idea that you can’t do anything without the largesse of corporations,” she told Fast Company. “You start to think that collectively as citizens you can’t even do basic things like have a music festival or a block party—or educate your kids—without some sort of sponsorship.” But it would be well worth it to untangle brand influence from culture. “It’s important for any healthy culture to have public space—a place where people are treated as citizens instead of as consumers,” Klein told Fast Company.

Below, an examination of how one company bent its innovation from inventing things to inventing culture:

1902: A CAMPING UTENSIL

This is a patent for a camping pan with a removable handle, filed by A&F founder David T. Abercrombie. Camping pans today still usually have removable handles.

1902: CAMPING OUTFIT

This “outfit” isn’t a set of clothes for camping. It’s a sort of fold-up cabinet. We can imagine Roosevelt taking this with him to Africa.

1930: TELESCOPIC RIFLE SIGHT MOUNTING

Another example of Abercrombie designer-invented functional gear for outdoor sports.

1954: TENNIS BAG

In the 1950s and ’60s, Abercrombie & Fitch’s patents expanded beyond camping and hunting equipment to include gear for more suburban pursuits, such as tennis and traveling.

David T. Abercrombie’s camping utensil patent. (Illustration: David T. Abercrombie)

David T. Abercrombie’s camping outfit patent. (Illustration: David T. Abercrombie)

Store façade patent. (Illustration: Michael Jeffries)

Fragrance bottle patent. (Illustration: Adam Ebert)

1972: SHOE SOLE

Abercrombie & Fitch filed for bankruptcy in 1977. Before that, its designers continued to file patents, such as this one for a golf shoe sole.

2005: STORE FACADE

Google has no patents on file for Abercrombie & Fitch in the time immediately after Michael Jeffries became its CEO in 1992. However, its later patents under Jeffries—including this one, by Jeffries himself—make clear the store’s transition from selling items to selling an aspirational image. Many outlets have reported on Jeffries’ exacting control of the look and feel of his stories, including the staff.

Here, Jeffries patents a design for a storefront for Abercrombie offshoot Ruehl No.925, a clothing brand aimed at young professionals. “He described potential customers as having graduated from college in Indiana and moved to New York City,” Bloomberg reports. The storefront, which was meant to go inside malls, was supposed to resemble a Manhattan townhouse, with a little wrought-iron fence in front. All Ruehl stores closed in 2009, according to Bloomberg.

2011: FRAGRANCE BOTTLE WITH STOPPER

This flower-topped perfume bottle design is about as far from Abercrombie & Fitch’s origins as you can get. It looks a bit like the bottle for Justin Bieber’s Someday perfume, which started selling the same year this patent was filed.

Sometime after the recession, Abercrombie & Fitch lost its cachet. Analysts offer a number of reasons. Teens now favor fast fashion stores, like H&M and Forever 21. Abercrombie clothes are pricey; young people today prefer to spend their money on smartphones and other electronics that didn’t exist in Abercrombie’s heyday. Plus, there’s a growing strain of acceptance and inclusion in American pop culture that’s at odds with Jeffries’ stated goal for his company, to create a brand about exclusivity, beauty, thinness, and being one of “the cool kids.” Jeffries left the company this December, which was major news, as it was his tight control over Abercrombie’s image that most analysts credited to bringing the company around after its bankruptcy.

Will the company be able to re-invent itself for the next generation? Perhaps any future patents it files will offer some hints.