The “Harlem Shake”—a pop culture phenomenon that’s part dance and part costumed chaos, all performed to a techno song created by Brooklyn-based electronic music producer and DJ Baauer—has taken the world by storm, topped the Billboard charts, and sent YouTube into convulsions. The original 30-second video on the site went viral and has attracted more than 12 million views so far. But like a virus, the real point of the Shake is to replicate, and subsequent “Harlem Shake” videos collectively created and uploaded by imitators have garnered more than 175 million views to date.

A typical video goes as follows: one person, usually in costume— say, a feather boa and a pink onesie— begins to dance or shake their torso, while others in their company look on, seemingly unaware. Ten or so seconds into the video, the others suddenly appear in costume shaking to their full potential.

While the Shake originated in Harlem in the 1980s, the dance resurfaced when Baauer laid down some new beats to complement the old shimmying movement. Predictably, the young embraced the dance first. College campuses around the world have hosted their own Harlem Shakes in recent days including University of California Santa Barbara …

http://youtu.be/gvEim1glg2M

… and Western University, to name a few.

The University of Georgia’s men’s swim and dive team managed to move the dance underwater where they (impressively) break it down at the depths of the school’s pool.

This dance is not just for the young. A CBS News Team, firemen (in a firetruck!), and a battalion from Norway’s army have performed their own renditions (and attracted millions of views).

But as a dance craze, the “Harlem Shake” is not original for its movement, or, given “Gangnam Style,” for the moment.

Arguably, this dance move is a cross-cultural phenomenon that never totally died out. Before the Harlem Shake videos of late blew up on YouTube, the shimmy—much like the Shake—has long been a traditional belly-dancing move, performed in the Middle East as early as the 12th century.

In the modern era, popular songs like “I Wish I Could Shimmy Like My Sister Kate,” released in 1921, and Mae West’s appropriation of the dance, testify that trends of rhythmic shaking have shimmied through America since the early 20th century.

West’s description of the shimmy encapsulates these sentiments and may explain why she was one of the first white women to famously incorporate this move into her own shows: “[Dancers] stood in one spot, with hardly any movement of the feet, and just shook their shoulders, breasts, torsos, breasts, and pelvises. We thought it was funny and were terribly amused by it. But there was a naked aching, sensual agony about it, too.”

International stars including Beyonce, Britney Spears, and Shakira regularly wriggled, writhed, and of course, shimmied in their music videos and live performances over the last decade. And any time in the last couple years, you could turn on “Dancing With the Stars” and expect to see a contestant or two to break into a variety of torso spasms.

Nor is the Shake unique for its combination of hilarity and sexuality, which a recent NPR article argues, are essential components of any dance craze.

Shimmying, or in this case, “Harlem Shaking,” arguably blends comedy and sensuality quite overtly—how else could you explain video after video of scantily (and ridiculously) clad people doing inane things like spastically gyrating or, in one video, a dancer’s decision to air hump another Shaker in a green gorilla suit?

What’s more, the videos where the Shake is done in the most absurd settings tend to get highest viewership.

Much of the same can be said for the Harlem Shake’s immediate dance craze predecessor, “Gangnam Style.” In “Gangnam Style Decoded,” the Global Post’s Asia Editor Emily Lodish suggests that the popularity of South Korean rapper Psy’s song—which launched the now famous horse dancing routine—can be explained by its “mix of the familiar and the erotic,” which she credits as a recurring “recipe for success” where dance crazes are concerned.

His “clownish” self-representation makes him “very accessible” said Lodish, in reference to the many scenes where he parades around Gangnam, one of South Korea’s wealthiest neighborhoods, in bright suit jackets, bow ties, and a loud set of shades.

While many dance crazes are undoubtedly silly, they are also arguably irresistible. (I’ve found myself joyfully succumbing to riding a fake pony in the last couple months, and I still do the Macarena from time to time.) Additionally, dance fads may be understood as challenging, or representing, the angst of an age.

“Gangnam Style” could be considered a response to growing economic inequality in South Korea and on an international stage; “Harlem Shake” seems more a like release as it allows its participants to devolve into chaotic merriment together—offering a break from the demands of everyday rigors.

Baauer explains his song’s popularity more simply: ‘I think it caught on because it’s a goofy, fun song,” he told The Daily Beast. “But at the base of it, it’s my song and it’s making people want to dance. That’s the best feeling in the world to me.”

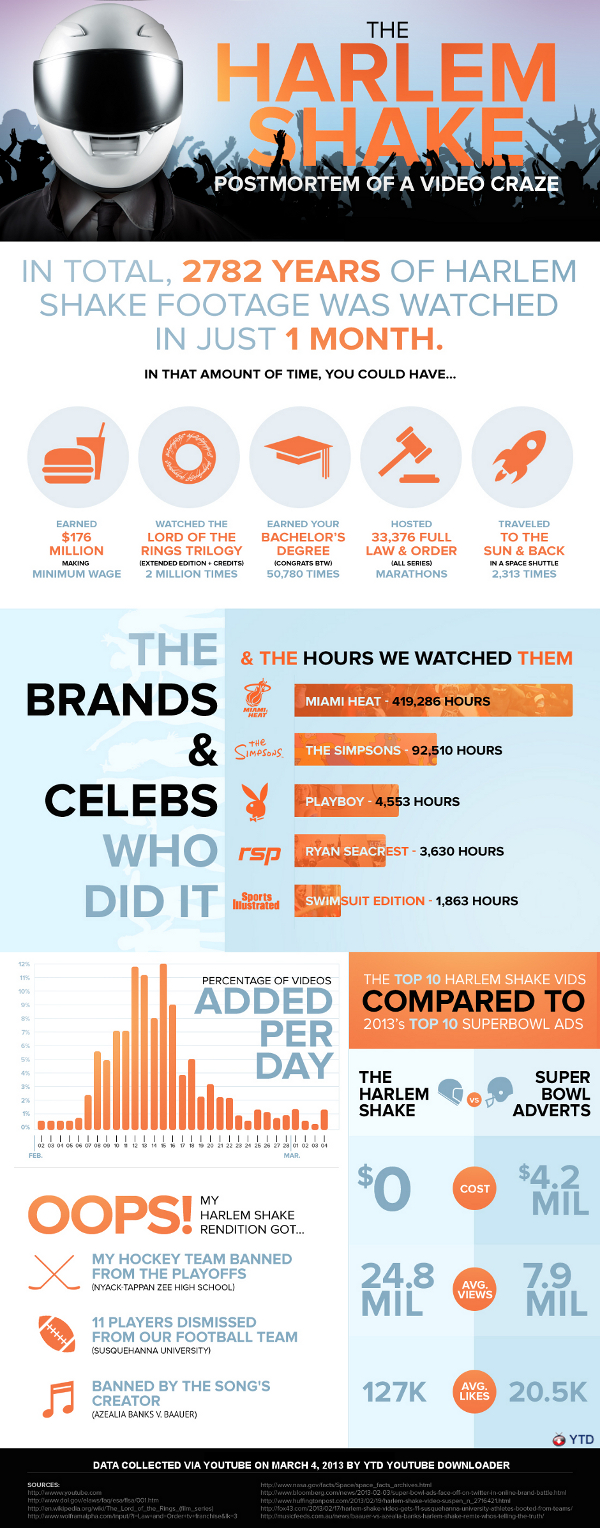

UPDATE: Meanwhile, it now seems humankind has spent, collectively, almost three millennia doing the Shake, as this graphic details.

Harlem Shake | Postmortem of a Video Craze – An infographic by the team at YTD Youtube Downloader