Now that the GOP’s long-awaited tax reform legislation, the “Tax Cuts and Jobs Act” (TCJA) has finally been released, the wonks are out in full force. Over the past several days, economists have been pouring over the legislative language and running the numbers on the plan. Now a clearer picture of the plan’s long-term effects is starting to emerge—and, for middle-class Americans at least, the outlook is not so rosy.

The chart below is from an analysis released Tuesday by the Joint Committee on Taxation, the congressional committee responsible for evaluating and scoring tax legislation. It shows the percentage of households at different income levels that would see tax cuts or tax increases in 2019:

In 2019, 61 percent of households overall would see their taxes fall by at least $100, 30.7 percent would see a minimal tax change (less than $100), and 8.3 percent would see a tax increase. Among households earning $40,000 to $50,000, 7.9 percent would see their taxes increase. For households earning between $50,000 and $75,000 a year, about 9.6 percent would see a tax increase. By contrast, a higher percentage of households in the top income brackets—21.7 percent of those earning between $500,000 and $100,000 and 23.8 percent of those earning over $1 million a year—would see tax increases in 2019 under the GOP’s tax plan.

This happy tax-cut picture, however, changes a lot when you look at what happens down the road. Here’s the Joint Committee on Taxation’s distributional table for 2025:

By 2025, 39.3 percent of filers would see a tax cut, as compared to current law, of at least $100. Just over 22 percent, meanwhile, would see tax increases. Among middle-class families, 24.7 percent of those earning $40,000 to $50,000 would see tax increases, and 27 percent of those earning $50,000 to $75,000 would see increases. (Even higher percentages of top earners would see increases in 2025.)

Ernie Tedeschi, a policy economist at Evercore ISI and former economist for the United States Department of the Treasury, points out that there’s one group of taxpayers that’s particularly hard-hit by the structure of this tax bill: parents with children under the age of 18. The chart below, from Tedeschi’s blog, shows how the legislation will affect those households in 2027:

According to Tedeschi’s analysis, 20 to 24 million families (depending on how the effects of the corporate tax cut are distributed) would see a tax increase in 2027, as compared to current law. That’s a whooping 45 to 55 percent of families with children under the age of 18.

One of the big reasons so many families would see their tax bills increase in the long-term is that several of the credits in the legislation designed to help middle-class families are phased out for cost reasons, to comply with Senate rules. Republicans, in turn, have argued that Congress would be unlikely to allow these credits to expire so these tax hikes would never actually materialize. Tedeschi looked at what would happen if the credits were renewed, as the GOP has suggested they would be. He finds that making the credits permanent would slightly reduce the number of families facing tax hikes, but only by about 4 percentage points, because other changes in the law also hurt families. Here’s how he explains it:

[T]he law makes several changes—elimination of the personal exemptions, a rise in the lowest bracket to 12%, a slower inflation adjustment for benefits like the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC)—that hurt families. Often the changes the law makes in support of families such as the increases in the standard deduction and the child tax credit, and the introduction of the filer and nondependent credits, are not enough to make families whole. In other words, even if these credits become permanent and even giving the plan the benefit of its corporate tax cuts, more than 40% of parents face a tax hike under the TCJA.

His findings are consistent with a smart New York Times analysis from Ben Casselman and Jim Tankersley, which concluded that, “[b]y 2026, 45 percent of middle-class families would pay more than what they would under the existing tax system.”

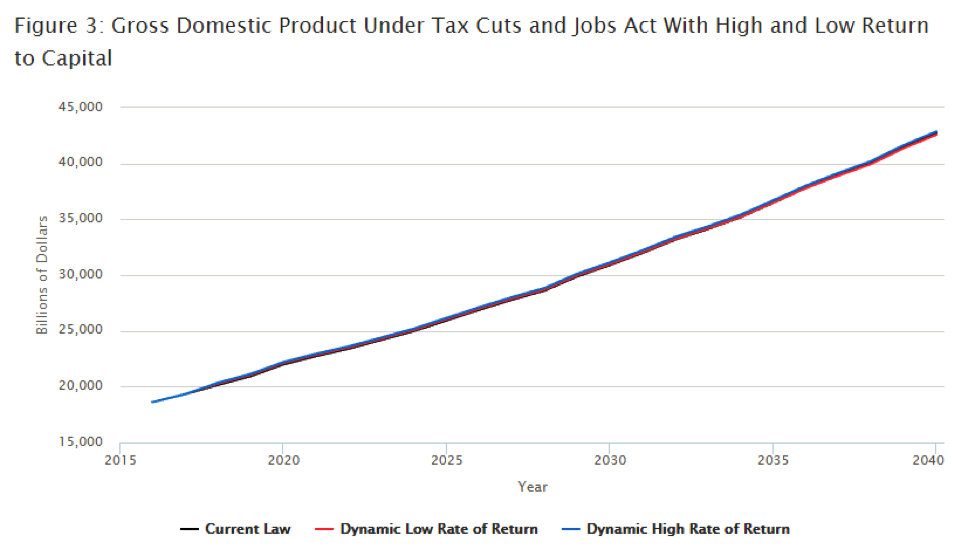

The GOP’s argument has long been that its tax reform legislation will produce enough economic growth to mitigate any negative effects for middle-class families. But another analysis out this week—this one from the Penn Wharton Budget Model initiative—projects pretty unimpressive gross domestic product (GDP) growth effects from the legislation. The analysis concludes that, while the TCJA would increase GDP, it wouldn’t be by much. The chart below, from the Penn Wharton analysis, illustrates projected GDP under current law, and under the TCJA:

As you can see, there’s not much daylight between those three lines—the analysis concludes that the legislation would increase GDP by only 0.33 percent to 0.83 percent in 2027. What’s more, the Penn Wharton researchers conclude that the extra debt resulting from the TCJA—they project the legislation would increase federal debt by $6.3 to $6.8 trillion by 2040 (after economic growth is accounted for)—could be bad news for long-term economic growth.

“[T]his small boost fades over time, due to rising debt,” the analysis concludes. “By 2040, GDP may even fall below current policy’s GDP.”