The environmental cost of agribusiness expansion into the Amazon basin and the Cerrado savanna isn’t limited to the felling of forests and destruction of native vegetation to make way for crops. Agribusiness growth there also requires major new transportation infrastructure corridors—railways, roads, industrial waterways, river ports, and other logistic support—to efficiently move soy and other crops from the Amazon and Cerrado interior to market in China, the European Union, and elsewhere.

If precautions aren’t taken, this infrastructure could do great damage to the environment, and indigenous and traditional communities, particularly due to the population influx they inevitably trigger.

Over the last 20 years, grain production has exploded in northern Mato Grosso state, and today the process is being repeated in Matopiba, the agribusiness acronym for the parts of the Cerrado savanna biome located in the states of Maranhão, Tocantins, Piaui, and Bahia. The Cerrado is the scene of Brazil’s most recent agribusiness expansion, as cattle, soy, corn, cotton, and eucalyptus rapidly replace native vegetation.

While the agricultural boom has been very quick, the building of new infrastructure has been much slower, so transport bottlenecks have emerged all over the region, most notably on the inadequate roads of northern Mato Grosso and Pará states. New highways are being built and old ones paved, but their capacity is being overwhelmed even before they’re completed.

The result: bumper-to-bumper Amazon traffic jams that delay delivery and eat into agribusiness producer and commodity company profits.

Some see the construction of railways and industrial waterways as the best long-term solution for this logistical nightmare. Rail and water transport bring down freight charges and trains emit far fewer greenhouse gases than trucks. Today, many in Brazil’s interior are putting their hopes for new infrastructure in Chinese investment and construction. But there are serious downsides to this potential development, especially when routes cross protected areas and indigenous reserves.

A Brief History of Amazon Rail

Surprisingly few railroads have been built in Amazonia. Most famous is the catastrophic Madeira-Mamoré railway, built between 1907 and 1912 to link Porto Velho to Guajará-Mirim in western Brazil. The goal: provide a way to rapidly move rubber tapped in Bolivia to Amazon streams, for shipment to Europe and the United States. In the longer term, planners also dreamed of linking the Pacific and Atlantic oceans—an ambition being revived today.

The Madeira-Mamoré line was quickly dubbed the “Devil’s Railroad” due to the thousands of construction workers who died from tropical disease and violence. Legend says that a corpse is buried under each sleeper. Though completed, the railroad was soon abandoned when the rubber boom went bust.

More economically successful is the 554-mile railroad that annually hauls 120 million tons of iron ore from the huge Carajás mine in Pará state to the port of Ponta da Madeira in Maranhão state. But, in an indication of the trouble that could lie ahead for future railways, the line has caused many conflicts with communities, particularly the Gavião indigenous group. The Gavião have repeatedly complained that the railway divided their land in two, disrupting their lives and frightening away the animals they hunt, yet they haven’t received the compensatory help promised by the mining company.

Despite these problems, powerful sectors of the Brazilian government, along with transnational trading companies, such as Cargill, Bunge, and Amaggi, and farmers, have long fantasized about installing a vast integrated rail network, crisscrossing the Amazon basin, to provide efficient transport links to get commodities to market. But in the past, this was just that—a fantasy.

Today, however, many businesspeople believe the coming together of key factors is putting the dream within grasp. The first concrete step will likely come with the construction of Ferrogrão (Grainrail), which could carry soy produced in northern Mato Grosso to the Tapajós and Amazon rivers. But that would be just a start toward an Amazon rail network.

Brazil’s Place in China’s Belt and Road Initiative

China, with its 1.3 billion people, has long seen food security as a key objective of its investment strategies and international trading relations. In recent years that goal has assumed new urgency. According to Professor Peter Williams, a United Kingdom-based climate scientist: “Sooner or later, there will be an unbridgeable gulf between global food needs and our capacity to grow food in an unstable climate. Inevitably, starvation will reduce the world’s population.” Williams continues: “China is positioning itself for the struggle to come—the struggle to find enough to eat. By controlling land in other countries, they will control those countries’ food supply.”

(Photo: PughPugh/Flickr)

One way of ensuring national food security is by improving international supply routes. In 2014, President Xi Jinping announced an ambitious plan to integrate China’s supply networks across much of the world. Called Belt and Road, the initiative is envisioned as a 21st century Silk Road, composed of a “belt” of land transportation corridors and a “road” of sea routes and ports, with every path leading from vital commodities resources into China.

Environmentalists have responded to Belt and Road with deep concern, as it could offer a means for plundering the world’s forests and minerals, potentially at the expense of local economies, the environment, and indigenous and traditional communities.

At first, the initiative was limited to Asia, Europe, and Africa, and it seemed Brazil would not benefit. But, at a meeting of the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States in January of 2018, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi formally invited Latin America to join. Importantly, Chinese analysts see the U.S. as retreating from Latin America and are keen for their country, and its state-owned businesses, to fill the vacuum.

Roberto Jaguaribe, president of the Brazilian Agency for Export Promotion and Investments (Apex-Brasil), welcomed this Chinese invitation as a great opportunity for Brazil, saying that Chinese investment in railways, energy generation, and other sectors is “essential” for national economic growth. “Brazil is a strategic partner of enormous importance [for China]” Jaguaribe said. “We need to construct a relationship grounded in economic complementarity and in the great convergence of interests that exists between the two countries.”

This “convergence of interests” is born out of a simple reality: Brazil is a leading exporter of primary goods—crops, meats, and minerals—for which China has a growing need.

Soy Is King in Brazil and China

The dovetailing of national priorities comes together perfectly in one product: soy. As the Chinese population increasingly adopts a Western-style diet, the country needs more and more soy to use as animal feed for pigs and poultry. Today, China is a voracious consumer of soy on the world market, importing about 60 percent of the soybeans traded worldwide.

As a result, Brazil has become economically dependent on China, which buys no less than 80 percent of its soybean exports. The next most important buyer from Brazil is Spain, which purchases a meagre 2.9 percent share of its soybean exports.

This dependence is, of course, a two-way street, with China increasingly reliant on Brazil for its food security. China bought 95.5 million tons of soy in 2017, an increase of 13.8 percent over 2016. Of this, Brazil supplied over half—50.9 million tons, with Brazil’s share of China’s soy imports that year increasing by a massive 33.3 percent.

The main loser has been U.S. farmers. The U.S. was still an important supplier of soy to China in 2017—in fact, the only other significant supplier—selling 32.8 million tons to the Chinese. But this represented a 3.8 percent decline compared with 2016.

Moreover, this decrease may be modest when compared with what could be coming down the pipeline. President Donald Trump’s trade war with China has resulted in the Chinese government imposing a 25 percent tariff on U.S. soybeans, in retaliation for levies that Trump placed on a wide range of Chinese imports, and it has also virtually stopped buying U.S. soy. “The latest federal data, through mid-October, shows American soybean sales to China have declined by 94 percent from last year’s harvest,” the New York Times reports. This shift in trade could have a dramatic negative impact on U.S. soy exports to China into the future, while greatly benefiting Brazil. But that can only happen if Brazil has the transportation infrastructure with which to feed China’s need.

China Moves Into Brazil’s Soy Sector

With the Asian nation so dependent on Brazilian soy, the Chinese government wants to gain increased leverage over the Latin American supply. One approach has been to buy up land in Matopiba. But, more importantly, China is moving full force into commodity trading and the construction of transportation infrastructure—now applying its Belt and Road strategy to South America, and especially to the Brazilian Amazon and Cerrado.

Through state-owned COFCO, China’s largest food and agricultural company, it has bought up several trading companies. This move gives China independence from the powerful Western ABCD transnational trading quartet (ADM, Bunge, Cargill, and Louis Dreyfus).

China has also bought its own Brazilian port at São Luís do Maranhão on the Atlantic Ocean and purchased a leading engineering company, CONCREMAT, which now operates as a subsidiary of the state-owned Chinese company, China Communications Construction Company, one of the world’s largest builders of railways and industrial waterways.

In what, over the long term, may prove its most important strategy, China is also showing interest in investing in transport infrastructure. One of its key goals is to create alternative supply routes to the Panama Canal, which it views as being under U.S. control.

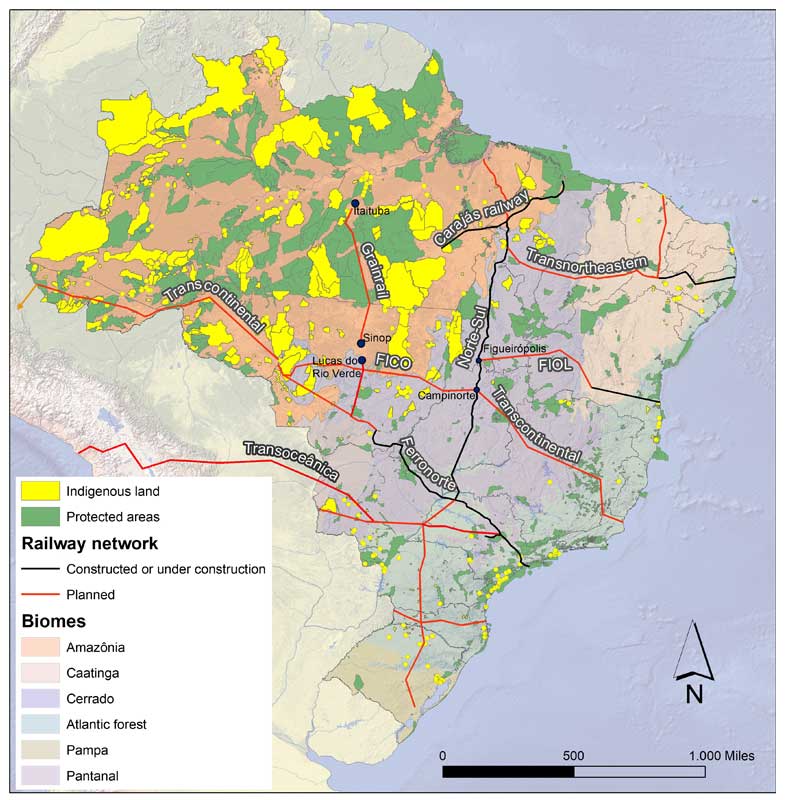

(Map: Mauricio Torres)

Chinese ambitions mesh well with those of Brazilian agribusiness, which is desperate to improve transport infrastructure, but can’t due to the national economic crisis and the Lava Jato corruption scandal’s disastrous impact on the once powerful Brazilian construction industry. As U.S. and European interest in Brazil flags, China’s role rises.

China is already in line to play a major part in the construction and operation of Grainrail. Elsewhere, China is involved in negotiations to help build and run two other major new Brazilian rail lines. One is the proposed FICO (the Railway for Integration of the Center-West), which would cut across the Amazon states of Rondônia and Mato Grosso, pass through two important soy producing areas near the towns of Agua Boa and Lucas do Rio Verde, and link up to the east in Campinorte in Goiás state with the Ferrovia Norte-Sul (North-South Railway), which has just begun construction.

The Ferrovia Norte-Sul, when fully operational will connect Brazil from north to south, extending more than 2,485 miles, and stretching from Belém at the mouth of the Amazon River, through the states of Tocantins, Goiás, São Paulo, and Rio Grande do Sul. The Chinese have expressed “strong interest” in investing in this railroad, though no concrete plans have been announced. There are also plans to build a railway linking to the Ferrovia Norte-Sul, known as the Northeastern, which would move Cerrado produce to the Atlantic coast for export.

At the same time, there are other plans to extend the EF-364, widely known as the Ferronorte line, (which currently ends in Rondonópolis in Mato Grosso state), as far north as Lucas do Rio Verde and then possibly to Sorriso, also in Mato Grosso. Whether China may play a role isn’t known.

According to a press briefing from Valec Engenharia, the state company running FICO: “There are political plans, not yet properly defined, to form a ‘great junction’ in Lucas do Rio Verde, integrating FICO, Ferrogrão [Grainrail] and Ferronorte.”

Soy producers in northern Mato Grosso see this new rail infrastructure as the best way of bringing down transportation costs and improving profits. Odir José Nicolodi, a soy producer from the hamlet of Santiago do Norte, said: “The project is ready and we, the farmers, are determined to join forces with the municipal authorities to help get the project off the ground.”

In November of 2017, Mato Grosso governor Pedro Taques traveled to China at the head of a Brazilian delegation and visited the CCCC. He came back confidently saying: “We need FICO and the Chinese are interested in financing it.”

Another railway that interests China is the Ferrovia de Integração Oeste-Leste (FIOL), the West-East Integration Railway, which would run from the future port of Ilhéus on the Atlantic coast of Bahia state, west to Figueirópolis in Tocantins state in the Cerrado. In Figueirópolis it would link up with the Norte-Sul railway.

When Brazilian President Michel Temer visited China in November of 2107, the state-run China Railway Construction Corporation—one of the largest railway construction companies in the world—declared its interest in forming a consortium to build FIOL. Since then, the Bahia state government has contracted a private consultancy, Accenture, to develop the project.

There would almost certainly be strong objections to some of these new railroads from environmentalists and indigenous communities, as many of the lines would penetrate or impact a variety of conservation units and indigenous lands. However, at this early stage of the planning process, critics aren’t lodging their complaints, and are awaiting announcements of the precise routes of the various railways before evaluating impacts.

Transcontinental Railways

In the longer term, these many railroads would link up with another, the biggest and grandest of the lot, and the ultimate dream of Brazilian entrepreneurs since the early 1900s. Known as the Ferrovia Transcontinental (Transcontinental Railway) or the Bioceânica, it would extend Ferronorte west through the Amazon into Peru, and east to the Atlantic, providing the Chinese and Brazilians with a definitive alternative to the Panama Canal.

The transcontinental railroad was announced in 2015 by Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff, after she reached an initial agreement with the Chinese, and was proposed at a cost of US$70 billion. It would run coast-to-coast through Peru and Brazil, and link the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans. However, after the initial fanfare, little has been heard about it in recent years, though there are regular discussions about route, including talk of still another transcontinental railway altogether, this one through Bolivia. If built, that line, known as the Transoceânica, would reportedly cut Brazil to China trade time from 67 to 42 days.

It is the more northern railway through Peru that analysts fear could do the most damage to protected areas and indigenous reserves. In July of 2015, three Brazilian government officials took five Chinese rail experts along the entire proposed 2,200-mile route in a journey that took them 10 days. The most remote area they visited was in Acre, Brazil’s far western state.

(Photo: JuhaOnTheRoad/Visualhunt)

The rail line would cross three large indigenous reserves and an important protected area, the Serra do Divisor National Park, in Acre. This vast region has been practically abandoned by regulatory authorities, leading to lawlessness. Thiago Pinheiro Corrêa, from the Federal Public Ministry, said: “There are frequent reports of invasions [of indigenous land and protected areas] by illegal logging groups, drug traffickers, and predatory hunters.”

Indigenous groups there have been involved in a long struggle to win land rights. Even as the Chinese officials flew over the area, Nawa Indians were holding four Brazilian government officials hostage in the latest chapter of their 10-year struggle to get authorities to mark out their land boundaries, a conflict which has proved particularly difficult because a portion of the land claimed by the indigenous group overlaps Serra do Divisor National Park.

One of the indigenous leaders, Lucila da Costa Moreira, said that the government is dragging its feet because it wants to get the Nawa out. Even though the railway won’t cross Nawa land, it will run close and the Indians are fearful. “We are worried about the impacts [of the railway], and we shan’t get any benefit because we don’t export soy,” said Ninawá Huni Kui, vice coordinator of the Organization of the Indigenous People of Acre, the Northwest of Rondônia and the South of Amazonas.

Railroad Futures

The rail network sketched out in this article includes a bewildering array of proposed projects—with some probably remaining pipe dreams, or suffering long delays, or seeing significant changes in route before they are built—but there seems little doubt that moves are afoot to get at least a few underway, though likely not as fast as commodities producers would like. As Edeon Vaz Ferreira, from the Pro-Logistics Movement of Mato Grosso, told Mongabay in August: The Chinese “are arriving but more slowly than many expected.”

Importantly, it is as yet unclear how the October victory of the extreme right candidate, Jair Bolsonaro, as Brazil’s president will affect China relations. Bolsonaro said last year that he wanted to restore the U.S. as Brazil’s top partner and expressed concern that China was taking over the country, with its investments in mining, agriculture, ports, and airports. More recently, he vowed to restrict Chinese purchases of Brazilian companies, warning: “China isn’t buying in Brazil, it’s buying Brazil.” As strident as these remarks may be, however, Bolsonaro also strongly supports agribusiness, which desperately needs China for its markets and for its infrastructure investment dollars.

Now that Bolsonaro has to run the country, and is appointing advisers, new voices are coming forward. One is Paulo Coutinho, a University of Brasilia economist, who is coordinating infrastructure plans for Bolsonaro’s party, the PSL (Liberal Social Party). Under Bolsonaro, the PSL has grown very rapidly, increasing its number of federal deputies from just one in 2010 to 52 deputies after the recent election. It has suddenly become a force in Brazilian politics.

Coutinho is more nuanced than Bolsonaro. He notes that the PSL has an ambitious program for expanding railways, roads, and airports, but says that it will almost all be carried out by private capital, with state help limited to loans from Brazil’s development bank, the BNDES (National Bank of Economic and Social Development), during the construction phase. He added, however, that the new government would welcome Chinese investment: “Bolsonaro doesn’t want the Chinese to buy land, but he has nothing against them building railways.”

The future of Amazon railway expansion will almost certainly depend on the relationship that develops between Brazil’s Bolsonaro and China’s Xi. But it may also depend on Brazil’s stability under Bolsonaro. If the pre-election spike in rural violence worsens, with Bolsonaro supporters in the country’s rural interior moving aggressively to take over land in protected areas and indigenous territories, and to commit violence, the Chinese, renowned for their caution, might not push ahead with infrastructure investment plans, at least in the short term.

However, if Bolsonaro reins in rural supporters, tones down his aggressive rhetoric, and seeks accommodation with opponents, the incorporation of the Amazon into China’s Belt and Road initiative could well gain momentum.

This story originally appeared at the website of global conservation news service Mongabay.com. Get updates on their stories delivered to your inbox, or follow @Mongabay on Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter.