Last week, Senate Republicans passed a much-ballyhooed 2018 budget resolution. The resolution itself doesn’t have much of an effect, in Senator Bob Corker’s (R-Tennessee) words, “on anything whatsoever affecting the American people”—actual government spending levels, as well as any cuts to spending, should be negotiated later this year as part of a government funding package that will require support from Democrats. The budget resolution does, however, serve a key function: It lays out a framework by which the GOP can pass tax reform through the reconciliation process (with only 50 votes) and add as much as $1.5 trillion to the deficit in the process.

President Donald Trump, for his part, has been forcefully making the case that tax reform will act as a panacea for America’s struggling working class. Addressing a group of truckers in Pennsylvania earlier this month, Trump described the GOP’s tax plan as “a middle-class bill.” He also promised the attendees that they would see their wages increase by about $4,000 a year under the plan. To date, the tax reform details released by White House and congressional negotiators have been very vague, making it difficult to assess whether middle-class Americans will be helped or harmed by the GOP’s tax plan. A preliminary estimate from the non-partisan Tax Policy Center, however, suggests that the bulk (about 80 percent) of the benefits would accrue to the top 1 percent of earners, who would enjoy an average tax cut of over $200,000 a year. Americans in the middle fifth of the income distribution, meanwhile, would see a tax cut of about $420 a year, and some middle-class Americans would actually see their tax bill increase due to the elimination of certain deductions.

The GOP has disputed the report’s conclusions, arguing that their tax framework isn’t complete, and Trump has continued to promise that his ambitions are centered on the middle class, not the wealthy. But in an interview with Politico last week, Secretary of the Treasury Steven Mnuchin, who had promised earlier this year that the Trump tax plan would not benefit the rich, claimed that it’s hard to cut taxes without cutting taxes for the wealthy. “The top 20 percent of the people pay 95 percent of the taxes. The top 10 percent of the people pay 81 percent of the taxes,” he told Politico. “So when you’re cutting taxes across the board, it’s very hard not to give tax cuts to the wealthy with tax cuts to the middle class. The math, given how much you are collecting, is just hard to do.”

There’s some mathematical truth to Mnuchin’s statement. But the larger implication of the quote, as well as the entire GOP messaging operation—that the party and the president set out to write a tax plan to help working-class Americans and any benefits to the wealthy are just a happy accident—is a very tough pill to swallow at this point. There are, in fact, quite a few additional reforms the GOP could include in its tax package that would provide additional assistance to the middle class. (Nor are “across-the-board” tax cuts mandatory, by the way.)

And at a policy forum last week at Stanford University, a group of experts reminded us of some of those reforms. The forum, co-hosted by the Hamilton Project, LeanIn.org, and the Stanford Law School, focused on increasing economic opportunities for women; many of the policy proposals released in conjunction with the event are focused on the kinds of things that are perceived as “women’s issues,” but of course affect all Americans across the income spectrum: encouraging female labor force participation, increasing the economic security of older women, investing in child care, and establishing a paid parental leave program.

Also included in the forum’s accompanying e-book is a proposal from Hilary Hoynes, Jesse Rothstein, and Krista Ruffini that would go a ways toward helping working-class Americans: a 10 percent increase in the Earned Income Tax Credit. The EITC is about as close as you can get to an unambiguous success in the policy world. It enjoys bipartisan support. Researchers have found that it increases labor force participation, reduces poverty, improves maternal and child health outcomes, and strengthens children’s educational outcomes. Many states (27, and the District of Columbia) have, in fact, already added state-level EITC credits on top of the federal credit.

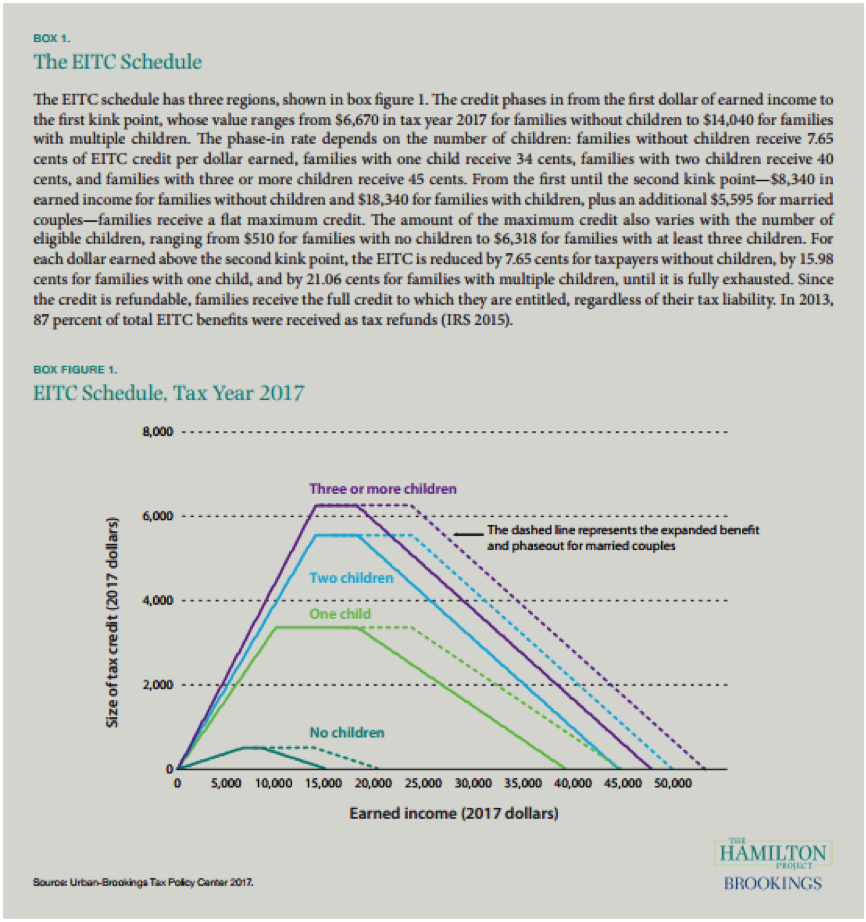

The figure below, from the Hamilton Project proposal, illustrates how the EITC currently works:

Hoynes, Rothstein, and Ruffini propose increasing the EITC, which has been frozen in inflation-adjusted terms since 1996, by 10 percent. The chart below, also from the report, illustrates what the new, expanded version would look like:

Such a change would increase take-home pay for EITC recipients, and the benefits of the expansion would be concentrated among those earning between $10,000 and $30,000 a year. “For example, a single mother working full time, year-round at the federal minimum wage, with two children, would receive an additional $560 under our proposal,” the researchers write. “This added income would make up for 86 percent of the decline in her real earnings since 2000.” The authors estimate that the expansion they propose would lift over 600,000 Americans out of poverty.

The Hamilton Project proposal is focused on increasing the size of the credit, not expanding the population that receives it, but there are proposals to expand the credit to more “middle-class” households as well. One, from Ro Khanna (D-California), would expand eligibility to households making up to $76,000 a year, and increase the size of the credit for both working families and childless workers.

Hoynes, Rothstein, and Ruffini estimate that their proposal would cost about $7 billion a year (Khanna’s is more expensive). That sum is equivalent to 10 percent of current EITC expenditures, and the researchers point out that it could be paid for by measures such as “raising tax rates or using base-broadening measures such as limits on tax loopholes and deductions that benefit the highest-income families.”

Look at that: a proposal that increases after-tax income for working-class Americans but not top earners.