Earlier this month, the Trump administration informed states that the federal government would now be open to state-level initiatives to impose work requirements or other conditions on Medicaid recipients. A number of red states had proposed such changes in years past but were rebuffed by the Obama administration. Now that the guidance has been issued, changes are likely coming fast. Even before the announcement was made, 10 states had already filed and were awaiting approval on various work requirement initiatives, and others are reportedly newly considering applying for such waivers.

In its letter detailing the policy change, the Trump administration attempts to argue that work requirements can further the objectives of the Medicaid program by potentially improving “Medicaid enrollee health and well-being.” (Several health policy wonks have suggested that this framing is a likely attempt to ward off forthcoming lawsuits arguing that Medicaid work requirements are illegal.)

But while the details of the waivers proposed so far vary from state to state, many of them seem to have one pretty clear objective: to severely weaken the Medicaid program by making eligibility so narrow, and the barriers to maintaining coverage so high, that the program simply withers away in some states.

Let’s start with Kentucky, where Republican Governor Matt Bevin’s waiver was approved by the Trump administration on January 12th. Kentucky’s waiver, portions of which apply to both the traditional and expansion populations, imposes work requirements and sliding scale premiums and eliminates both retroactive coverage and “non-emergency” medical transportation. It also imposes some pretty onerous new conditions on anyone who fails to pay their premium or doesn’t fill out the (extensive) annual paperwork required to verify their eligibility—those recipients would be locked out of the program for six months until they pay any past due premiums and also complete a financial or health literacy course.

(Photo: Scott Olson/Getty Images)

These changes are projected to have huge effects on Kentucky’s Medicaid expansion population. The state itself projects the changes will reduce enrollment by approximately 90,000 over the course of the demonstration. And as Joan Alker, the executive director of the Georgetown University Center for Children and Families, points out, these effects will likely be particularly painful in poor, rural areas. Kentucky is home to six of the 10 rural counties that have the highest percentage of adults on Medicaid.

The Kentucky waiver, however, isn’t even the worst of it. Five states—Kansas, Mississippi, Alabama, South Dakota, and South Carolina—that didn’t expand Medicaid are planning to seek waivers permitting them to impose work requirements on the traditional Medicaid population; specifically, very poor parents. In Mississippi, which already has one of the lowest income thresholds for Medicaid eligibility for parents ($5,600 for a family of four, or 27 percent of the federal poverty line), the very poorest parents would now be subject to work requirements.

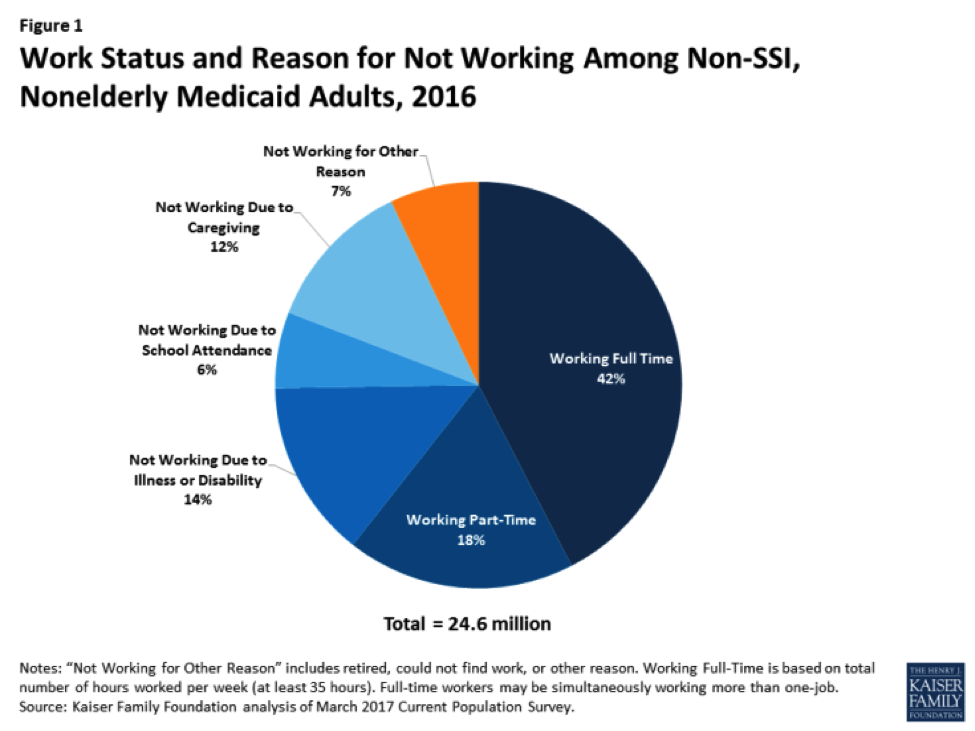

Let’s take a step back here and review some crucial facts about the people who receive Medicaid. As the chart below, from the Kaiser Family Foundation, illustrates, the majority (60 percent) of adult Medicaid recipients already work:

Nor is there much evidence in support of the central thesis driving this new Trump administration policy, which is the idea that Medicaid is currently serving as a disincentive to work for a bunch of lazy, free-riding, able-bodied adults. Of the remaining 40 percent of adult Medicaid recipients who aren’t working, 14 percent reported not working due to illness/disability, 6 percent reported not working because they’re in school, and 12 percent report not working due to caregiving responsibilities.

In fact, studies of the Ohio and Michigan Medicaid expansions found that enrollment in the program actually made it easier for recipients to both seek work and continue working. Sixty-nine percent of Medicaid expansion enrollees in Michigan said that their coverage enabled them to perform better at their jobs.

Earlier today, the National Health Law Program, the Kentucky Equal Justice Center, and the Southern Poverty Law Center filed a lawsuit against the Department of Health and Human Services, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, and several senior HHS officials. The lawsuit argues that many of the changes to the state’s Medicaid program under the waiver violate federal laws governing Medicaid. Bevin, meanwhile, has threatened to eliminate his state’s entire Medicaid expansion if any portion of the waiver is blocked by the courts.