In June, Arkansas began rolling out a controversial change to its Medicaid program. Under a new state plan, all recipients who are able to work will have to log 80 working hours each month, or risk losing access to their health care. But finding a job might not be the biggest hurdle for many people.

In order to stay eligible for Medicaid, Arkansas’ recipients must report their working hours each month, and it must be done online—the state doesn’t offer a way to do it via mail, telephone, or in person.

This stings especially hard in Arkansas, which ranks 48th in the country for Internet access. According to BroadbandNow, 30 percent of the state’s population has access to fewer than two Internet providers. An estimated 20 percent have only a smartphone for Internet access at home. And in a state where 17 percent of residents live below the poverty line—ranked 44th in the country—even those with access might not be able to afford it.

“Work requirements would be harmful to our clients in any situation, but the online-only reporting requirements make it incredibly difficult,” said Kevin De Liban, an attorney with Legal Aid of Arkansas. He is leading a federal lawsuit against the United States Department of Health and Human Services, arguing that the federal government doesn’t have the power to approve changes to state health-care requirements at all, as the Trump administration did in March.

In some parts of Arkansas, “you don’t even have regular cell phone access,” he said. “If you have Verizon, and the sun is in the sky at a certain point, you might be able to get a bar or two of coverage.” Otherwise, he said, you’re often out of luck.

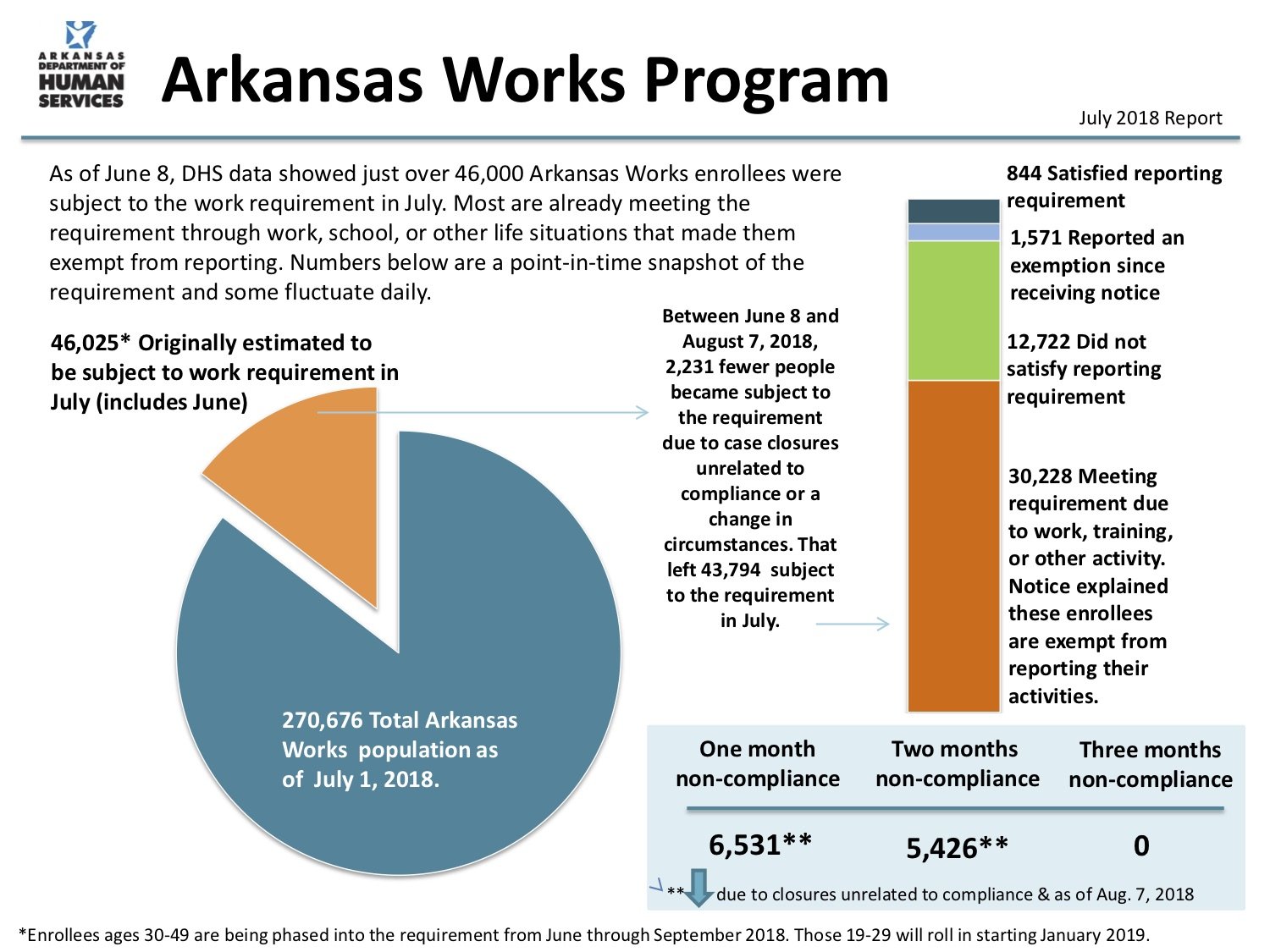

The new rules are being phased in in stages, and initial numbers suggest the first two cohorts are already in a precarious position. After the first month, about 7,000 people failed to report their working hours. That accounted for 72 percent of people in the first cohort, and 26 percent of all people on Medicaid in Arkansas. By the second month, 5,426 of the first cohort’s truants had failed again. In total, since June, more than 12,000 total have dropped off the reporting wagon. If recipients miss three months of reporting, they’re cut out of the system for the rest of the year.

It’s hard to parse where the reporting breaks down: whether it’s because people don’t have Internet access, couldn’t work enough hours, or something else. Some people may not have been successfully notified of the new reporting plan at all. “If Arkansas sends out a letter and the address is wrong, they just kick them off,” Joan Alker, executive director of the Center for Children and Families at Georgetown University, told the Los Angeles Times. “Arkansas is shedding enrollment.”

Sixty percent of Arkansas’ Medicaid recipients already work full time, according to the Kaiser Foundation. Of those who don’t, most have disabilities, familial obligations, or are in school—and for them, the process won’t change much.

(Graphic: Arkansas Department of Human Services)

It’s the rest of the recipients who are at risk from the latest changes, De Liban said, and with Legal Aid’s lawsuit he hopes to stop the changes before more cohorts are subjected to it. This lawsuit comes at the heels of another suit filed against Kentucky, which introduced its own work requirements this year. A federal judge struck the system down in June, calling it “arbitrary” and “capricious.”

After gaining federal approval to introduce work requirements in March, Arkansas told its first cohort about the new system in May, one month before the reporting mandates kicked in. Like Kentucky, officials there are claiming that working is good for your health.

Arkansas’ governor, Asa Hutchinson, insists that the work requirements are designed to help Arkansans, and strongly opposes the lawsuit. “This lawsuit has one goal, which is to undermine our efforts to bring Arkansans back into the workforce, increase worker training, and to offer improved economic prospects for those who desire to be less dependent on the government,” he said in a statement.

De Liban, however, says the state’s goal is to siphon people off state support without offering them a back-up plan. “Online-only reporting systems are administrative hoops, and when administrative hoops are there it’s easier for people to trip up,” he says. “And if they trip up they lose coverage, and if they lose coverage the state saves some money.”

While access poses one major hurdle for reporting, Internet literacy poses another even for those who have access at home. This factor splits across rural and urban lines even within the state. “Generally in rural areas people go online less and have less familiarity,” De Liban says. “Then when you add in socioeconomics, the digital divide becomes even more pronounced.”

Part of this divide has been driven by “digital redlining,” says Deb Socia, executive director of Next Century Cities, an organization that helps cities improve their Internet infrastructure and access.

“It’s not the government, but providers that have chosen to make additional investments in areas where it’s most lucrative, and to not improve infrastructure or provide better plans in low-income neighborhoods,” she says. That means urban, densely populated areas often have better broadband access than rural, predominantly low-income ones. And where access exists, users still have to pay for it. Those costs can be prohibitive, especially for those on government assistance.

Even those who have Internet access at home or somewhere nearby, the Medicaid reporting system itself can be difficult to navigate, De Liban says: Users have to create an email address, link health records to the reporting website using a reference number sent months earlier by mail, and click through multiple busy screens. The website only accepts reports between 7 a.m. and 9 p.m.

“One, we’re asking people who are very poor to figure out how to find access to Internet that’s not too expensive and can fulfill the need,” Socia says. “Two, we are presuming that they have the knowledge base to actually use it effectively. Those are two things we ought not assume or choose—and those two things should prevent us from implementing something like this requirement.”

To facilitate these transitions, states often hire case managers and set up programs to guide people into employment—albeit to varying rates of success—as well as compliance officers to keep people accountable.

But instead of hiring extra staff to train Medicaid recipients how to use the online system or to funnel them toward employment, the Arkansas Department of Health Services is allowing people to “designate a trusted individual to help them report their work activities or exemptions.” Two Arkansas insurance companies will provide these “registered reporters,” and the Arkansas Foundation for Medical Care is offering telephone assistance. The state’s health department says it will offer in-person help, too, at local county offices. But Arkansas is not getting federal aid to implement the new program, and state lawmakers say no additional money will be allocated to new hires this year.

If successful, Legal Aid’s lawsuit could mark the beginning of a string of challenges to these new work-requirement waivers. “Since Arkansas is the second state where this is being litigated, it’ll be a key indicator on the future of work requirements,” De Liban says. Utah, Kansas, Wisconsin, Ohio, Mississippi, and Maine have work requirements of their own pending; and waivers in Arizona, Indiana, and New Hampshire have already been approved.

And already, the Trump administration is attempting to challenge the Kentucky ruling by providing more evidence that work improves mental and physical health—a claim that has very little research to support it, and one the federal judge in the original case deemed “little more than sleight of hand.”

Even if lawsuits dismantle work requirements, Internet access in Arkansas and other disconnected states remains a significant challenge. Arkansas may be the third worst-connected state in the country, but the problem exists across the country: A quarter of all Americans have no broadband at all. That’s something policymakers at all levels will have to contend with if they want to make the Internet a central fixture of government operations.

Arkansas has received a little over $100 million in federal funds for broadband infrastructure projects since 2010, leading to slight gains in connectivity speeds over the last seven years. But in August, the U.S. Department of Agriculture committed to pouring $97 million into “rural broadband infrastructure” in 11 states. Arkansas isn’t one of them.

“Technology so empowers us to be able to communicate with one another, but it’s not an equitable method of communication,” Socia said. “The outcome is only as good as the input, and in this case the input has serious flaws.”

This story originally appeared on CityLab, an editorial partner site. Subscribe to CityLab’s newsletters and follow CityLab on Facebook and Twitter.