The recent death of Chester Bennington, the lead singer of the American rock band Linkin Park, left millions mourning the loss of an iconic musical pioneer. “Literally the most impressive talent I’ve seen live,” said Rihanna, another talent known for blending disparate genres to achieve unprecedented musical affect.

But even those unfamiliar with Bennington’s work might take a moment to appreciate how the death of this 41-year-old international star, an apparent suicide, highlights the reality that, as a demographic, rock ‘n’ rollers—not unlike football players—are trapped in a public-health crisis.

According to Professor Dianna T. Kenny, a developmental psychologist at the University of Sydney who has long studied the problem, “the rock scene is a volatile mix of danger and rebellion.” She contends that, “Given the inherent hazards of the pop music scene, and the taken-for-granted assumptions that pop musicians will live dangerously, abuse substances, and die early,” there needs to be more systematic research undertaken to address the issue.

Intensifying the matter is that the hard living that harms rock musicians tends to be romanticized. A culture that, for some reason, mythologizes the rebellious artist demands that good music come with a cult of personality. The consumption of art “valorizes outrageous behavior,” writes Kenny—all of which enhances the need for a more objective and sober look at the professional dangers inherent in being a full-time rock musician.

As Kenny summarizes the current research (in a chapter in the 2016 book Coping, Personality, and the Workplace: Responding to Psychological Crisis and Critical Events), the available data is deeply troubling.

One study of 1,064 popular musicians focusing on their lives after becoming well known found that “post-fame mortality was 1.7 times greater than demographically matched populations” in the United States and the United Kingdom. For the North American musicians in the sample, the median age of death was a remarkably young 35 years. Drug and alcohol use, as well as overdose, accounted for 25 percent of those deaths.

Another study, this one of 1,489 rock musicians, explored the question of the music industry’s association with risk taking and substance use. It found a strong correlation between the two, but noted that a clear causal factor was the pre-existing experience of childhood adversity. About 50 percent of musicians in the sample who died of substance use or excessively risky behavior had experienced some form of childhood adversity, thus raising the question as to what extent childhood adversity predisposes a child to a career in music.

Kenny’s own research is perhaps the most eye opening. She looked at 12,803 deceased rock musicians over six decades. Her data has been diced up and analyzed in many ways—by sex, cause of death, death rates by age bracket, etc.—but what’s especially interesting is how different kinds of death afflict different kinds of musicians.

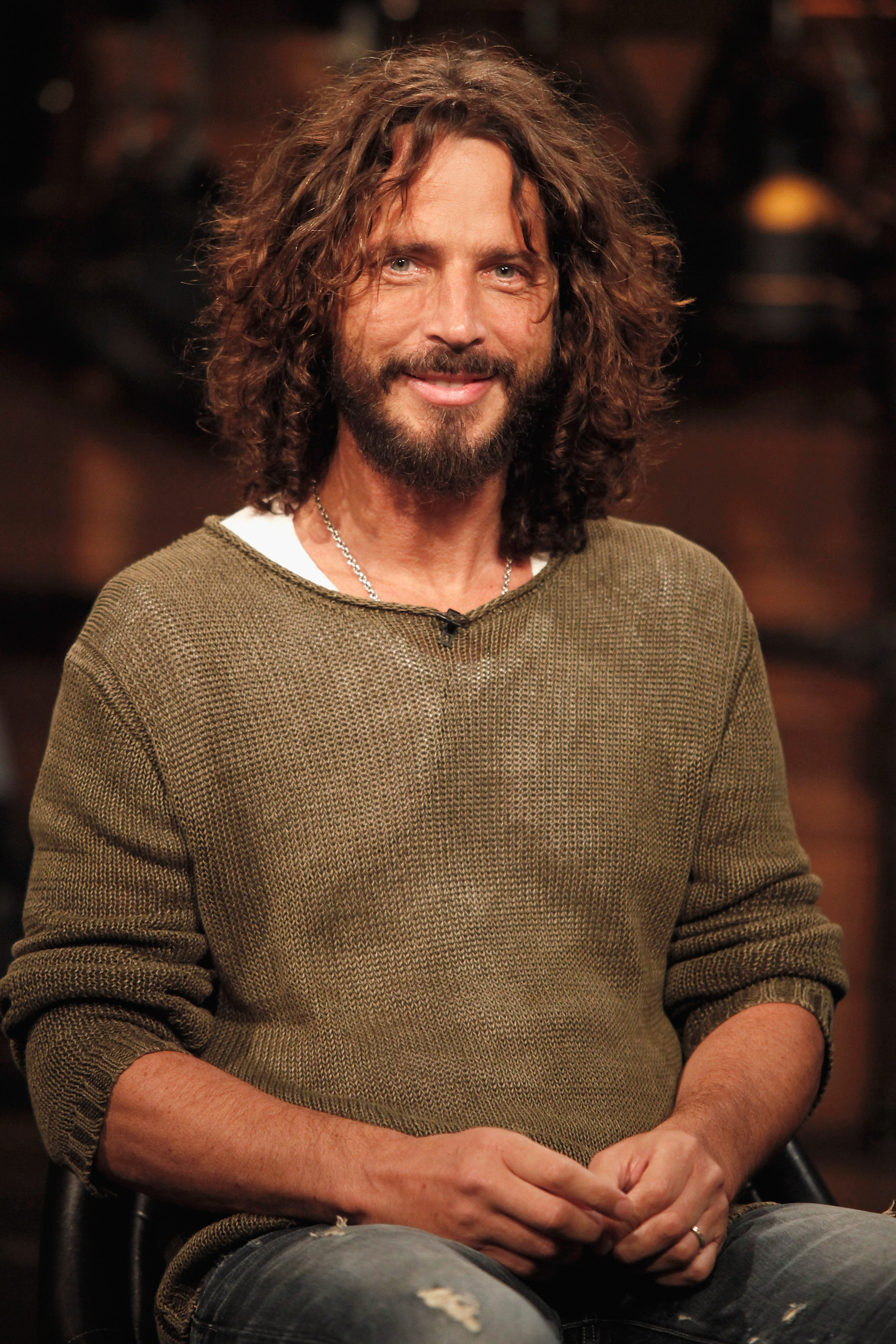

(Photo: Cindy Ord/Getty Images)

Death by accident represented 20 percent of all deaths, but 35 percent for metal musicians, 30 percent for punk rockers, and 25 percent of rock stars. Suicide accounted for 7 percent of all deaths in the sample, but 20 percent for metal musicians and 11 percent for punk rockers. Homicide was the cause of death for 6.3 percent of deaths but 51 percent for rappers and 52 percent for hip-hop artists. The safest type of musician to become, according to Kenny’s data, is a gospel singer.

Kenny’s assessments of her findings boils down to a single poignant question: “What aspects of the popular music scene are so pathological as to be associated with such disturbing patterns in morbidity and mortality, despair so profound as to result in risk of death by suicide, that follows popular musicians into old age, and rage so uncontainable as to result in either the commission of or becoming the victim of homicide?”

Although we have a ream of alarming data to look at, we currently lack adequate answers to this question. Seeking those answers will require framing the problems endemic to the rock ‘n’ roll lifestyle—drugs, alcohol, risky behavior, suicide—much as we’d frame any other workplace-related hazard.

One specific approach might be to carefully study bands and musicians who survived for decades while, despite inevitable setbacks, managing their careers, and their mental and physical health, with admirable equanimity. REM, which produced 15 studio albums between 1983 and 2011, comes to mind.

Another, and perhaps more important, approach would be to find ways to stop glorifying both the bad behavior of rock stars and their all-too-frequent suicides. Chris Cornell, the former lead singer of Soundgarden addressed this very issue just last year. He said: “People die of drug overdoses every day that nobody talks about. It’s a shame that famous people get all the focus, because it then gets glorified a little bit, like, ‘This person was too sensitive for the world,’ and, ‘A light twice as bright lives half as long,’ and all that. Which is all bullshit. It’s not true.”

A year later, he, too, killed himself. Chester Bennington sang at his funeral.