Why do so many women love selling to their friends? Last December, Pacific Standard spoke with joiners of a buzzy new multi-level clothing company, LuLaRoe, which sells branded shirts, skirts, dresses, and leggings via “consultants,” or people who have signed up to push their products. In the process, we tried to answer why American women are disproportionately likely to join multi-level marketing businesses, in which members earn commission from new members they recruit. LuLaRoe is just one of a new crop of such companies, which includes older institutions such as Amway, Avon, and Mary Kay.

Since then, LuLaRoe has introduced several new skirts, jackets, and a children’s sweater to its product line and recruited likely thousands more women to be independent sellers for the company (an estimate based on their past rate of growth). Despite these successes, LuLaRoe has, in the last few months, also faced serious criticism and lawsuits from both buyers and those who have recently signed up to sell their clothes.

Among recent reviews on Glassdoor, a site where employees rate employers, the most common criticisms are that the latest prints are ugly and difficult to sell; that the company’s rules for sellers change too often; and that selling is too time-consuming. Another top complaint: There are too many sellers in some cities, saturating the market and cutting sales for all. (This last complaint is a consistent one: We reported on it last year.) LuLaRoe’s reviews on Glassdoor currently average 2.5 stars out of five.

(Photo: LuLaRoe)

In addition, the company is facing new complaints that its clothes have declined in quality, tearing soon after they’re bought or even arriving in sellers’ shipments with holes already, as CBS New York reported in May. Two customers filed a class-action lawsuit in California, alleging LuLaRoe executives are “well aware that their Products are defective” and they “have chosen to sacrifice the quality of their Products in order to meet the growing demand at the expense of Customers.” The company has an “F” grade from the Better Business Bureau.

LuLaRoe has launched an initiative to refund its retailers for ripped merchandise, but the money has been slow in coming, sellers told CBS New York earlier this month.

“Multi-level” systems like LuLaRoe’s can be risky for sellers; some estimates find that as few as 1 percent of multi-level marketing sellers actually earn a profit. Multi-level structures can also encourage unsustainable growth if recruitment is more lucrative than retailing, and more sellers sign on than there’s a demand for. “If team-building is the most important, then saturation is inevitable, if they’re good at what they do,” Hamline University economist Stacie Bosley says.

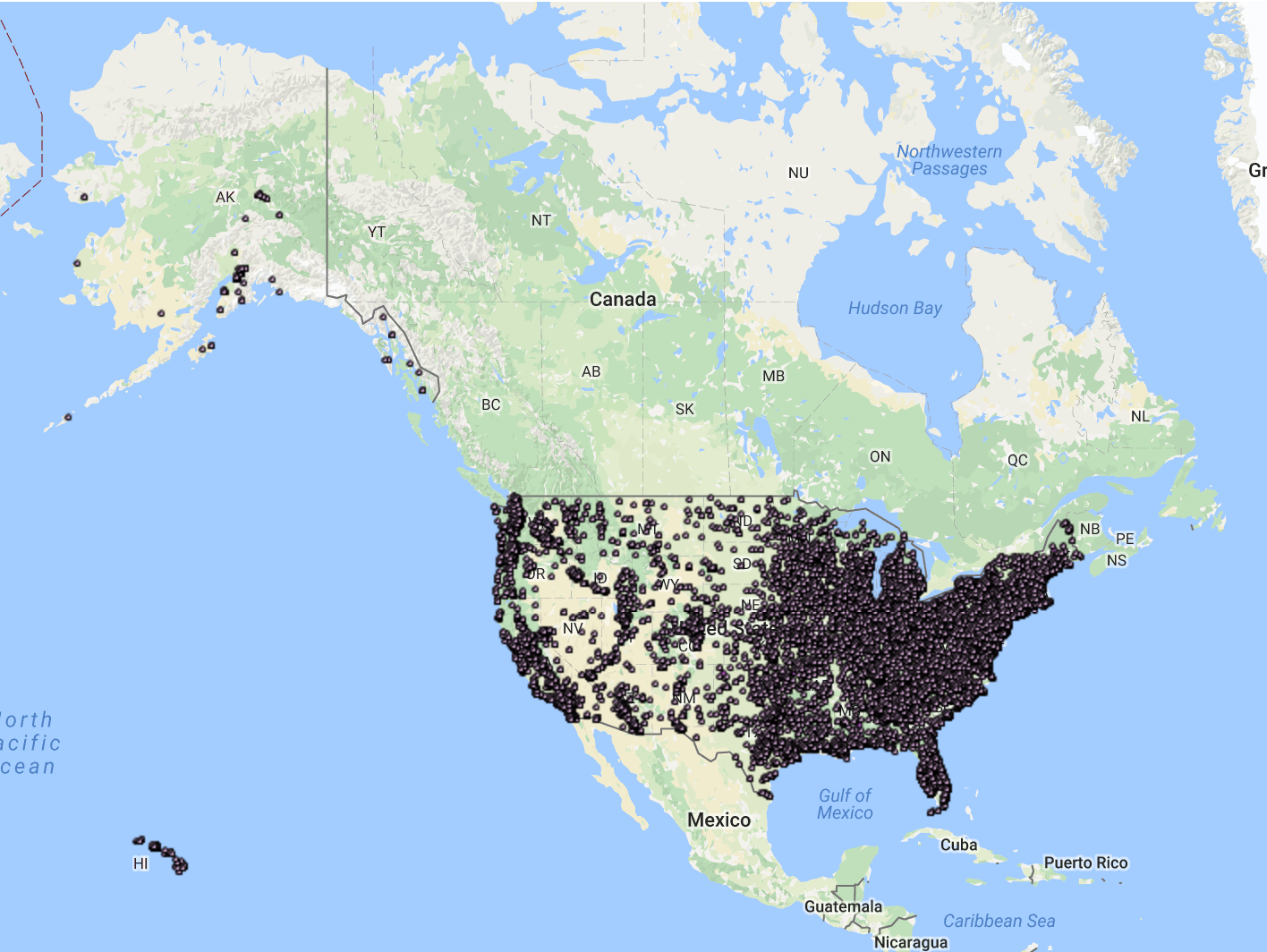

Between September of 2016 and February of 2017, the number of people signed up to sell LuLaRoe doubled, from 38,277 to 77,491, Business Insider reports. Even before that period, a repeated complaint on Glassdoor was that the company had signed up too many sellers too quickly. “The company is growing so fast they cannot realistically take care of their consultants,” one reviewer wrote in March of 2016.

Bosley says that economic theory suggests any company that sells a product that’s already established on the market—in this case, clothing—shouldn’t experience exponential growth. Not that that stops many companies from suggesting they’ll be different. “Multi-level marketing, even at its best, seems to think it’s beyond economics,” she says.