Even though economics and ecology both trace their origins back to the Enlightenment, they have always had an uncomfortable and antagonistic relationship. Today, however, Stanford University ecologist Gretchen Daily and a host of other scientists and economists are trying to finally bridge the gap between the two disciplines by attempting to put a price on nature — and not surprisingly, their endeavor has caused a little heartburn. Depending on how you view things environmental, the project is either breathtaking in its ambition or absolutely terrifying.

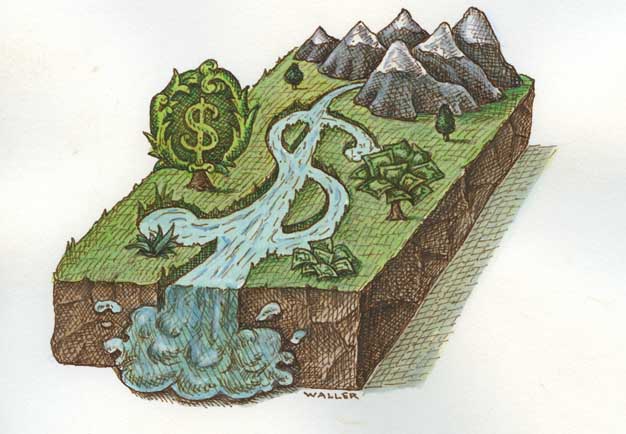

Whatever your ideological leanings, you’d be hard pressed to argue that nature counts for much now, at least in traditional economic calculations. Ecologists — and, more and more, economists — have elaborated on the idea that the Earth’s ecosystems constitute “natural capital,” a kind of ecological “principal” that, when managed properly, generates a sustainable flow of interest that supports life on the planet. But traditional economics is infamous for ignoring the real environmental cost of doing business.

“It doesn’t even appear on the balance sheet when you’re doing a cost-benefit analysis,” Daily says. “Natural capital never shows up there: It’s implicitly valued at zero.”

Daily and her associates think that determining the monetary value of “ecosystem services” — like carbon absorption, flood control, water filtration and all the other good things nature does — is the first step toward a truly sustainable human presence on the planet. Only by putting a price on nature, they argue, can we truly appreciate it — and know what parts of it are most important to pay to preserve.

But critics see an economic gloss on ecology as heretical, the opening of a Pandora’s box that would set the stage for a host of greedy owners of natural capital — from timber and energy companies to Florida swampland dealers — to extort more and more money from the government for each attempt to protect the environment.

Daily isn’t shy about acknowledging criticisms of her efforts to popularize the idea of ecosystem services. But she says something needs to be done to change the status quo — and quickly. “We’re in a desperate situation,” she says. “Nature’s always been kind of an all-you-can-eat buffet. We need to set prices, because without a price, it’s going to be a mad free-for-all and a race to the bottom.”

Though it may have been born in the realms of academia, the idea of ecosystem services is well on its way out of the academy gates. The Nature Conservancy, which spends about $700 million a year on conservation, has partnered with Daily and endorsed the concept. The U.S. Department of Agriculture already spends nearly $2 billion a year on farm conservation programs that help maintain ecosystem services, and it, too, is an emerging champion of ecosystem services. In 2005, then-U.S. Agriculture Secretary Mike Johanns announced efforts “to broaden the use of markets for ecosystem services (so that) credits for clean water, greenhouse gases or wetlands can be traded as easily as corn or soybeans.” Even China, the world’s last great Communist stronghold, has announced a $95 billion payments-for-ecosystem-services program.

As the market for carbon credits heats up, the concept of ecosystem services is clearly in ascendancy. Yet there is also a quiet debate about the ultimate consequences of the idea’s growing popularity — and whether it may, in the end, raise more snakes than it kills.

The idea of natural capital has been around since the late 1940s, and perhaps earlier. But it is only in the last two decades that the field of ecological economics has come into its own, its practitioners beginning to tease apart and put values on the various landscape-scale processes and functions of the natural world.

If a single year marks the real arrival of the concept of ecosystem services, it was 1997, when a paper titled “The Value of the World’s Ecosystem Services and Natural Capital” was published in the journal Nature by Robert Costanza and 12 other researchers. The group estimated the economic value of 17 discrete ecological benefits — from carbon sequestration in forests to water filtering in wetlands to wildlife habitat and ecotourism.

The point, Costanza says, was “to counter (the idea that) nature was really just a pretty picture, and we should preserve it because it’s pretty. There are all these other, more functional reasons that we hadn’t realized til fairly recently.” When the researchers added it all up, they arrived at an average of $33 trillion a year in value produced by the natural world — a total that was at the time nearly twice the global gross product.

The paper set off several debates in academia. Some economists criticized the authors’ methodology. But others raised moral concerns about the quest to value nature. In a special issue of Ecological Economics, University of California, Berkeley economist Richard Norgaard and several colleagues asked, “Will ecological economists bring us the value of God next?” They went on to ask just whom humankind might sell the Earth to “and what we might be able to do with the money, sans Earth.”

That was just one of the many critiques of the paper, but the second big event of 1997 — and the one that would ultimately generate the most press — was the publication of a book, edited by Gretchen Daily, called Nature’s Services: Societal Dependence on Natural Ecosystems.

The book became a lodestar for the ecosystem-services movement. It was the first attempt to lay out a systematic framework for inventorying and valuing the entire range of ecosystem services across the landscape. “Even imperfect measures of their value,” Daily wrote, “are better than simply ignoring ecosystem services altogether, as is generally done in decision making today.”

The book gave conceptual form to the emerging discipline. And the growing focus on the various processes that might be found on any given piece of land mirrored a larger shift, from the traditional conservation approach — which focused on protecting pristine ecological preserves — to a broader, landscape-scale approach that tried to keep the essential ecological process of larger ecosystem webs intact.

“Conservation’s becoming more complex than it was in the past, when you could go to a remote site, draw lines on a map and call it protected,” Daily says. “Most reserves are set up in rocks and ice, the places least contested for human enterprise. They’re too small, too few, too far apart, and things like climate change are going to maroon a lot of species in these kinds of areas.”

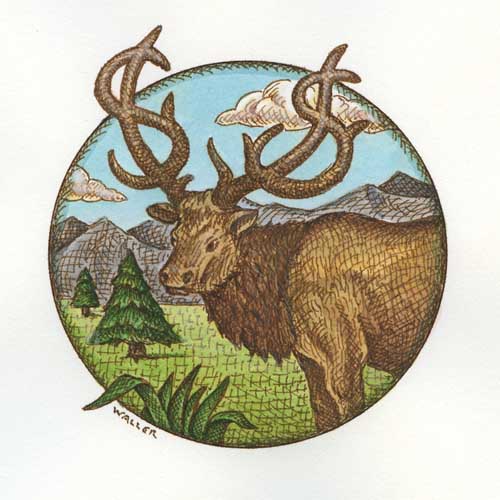

That realization has led to increasing attention being paid to conservation on privately owned lands. In fact, ecosystem services offer a more sophisticated way to do what environmental groups like The Nature Conservancy have long been doing: Putting conservation easements on private land, or even buying it outright, to prevent development and preserve important ecological functions on the land.

The ecosystem-services framework offered the possibility of even-more-finely targeted investments in environmental protection. It let government natural-resource agencies and conservation groups be more selective about the particular services they were trying to get and — theoretically — would allow them to focus on the lands that would yield the highest return on investment.

In the decade or so since 1997, the effort to quantify and promote ecosystem services has become increasingly sophisticated. It has also become much less theoretical and attracted more and more attention from major conservation organizations.

In 2001, more than 1,300 scientists began work on the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, a globe-spanning effort that its participants called “the first comprehensive audit of the status of Earth’s natural capital.” The assessment — the results of which were released in 2005 — looked at the health of 24 ecosystem services and, not surprisingly, found many of them severely degraded.

Then, in 2006, The Nature Conservancy and World Wildlife Fund — the world’s two biggest environmental organizations —teamed with Daily and Stanford’s Woods Institute for the Environment to create the Natural Capital Project. It is the first concerted effort to put practical meat on the bones of ecosystem-services theory and brings together a number of demonstration projects in California, Oregon, Hawaii, Mexico, Ecuador, Colombia, Tanzania and China.

In Tanzania’s Eastern Arc Mountains, for example, a team is assessing ecosystem services, including water supply, carbon sequestration, landscape preservation for ecotourism and forest products. The goal is to devise a framework under which local residents can be paid to maintain those services by, for example, protecting the forests that are essential for guaranteeing water supplies.

Perhaps even more important, the Natural Capital Project collaborators are developing a software system called InVEST, which is short for Integrated Valuation of Ecosystem Services and Tradeoffs. InVEST can analyze a particular area and “light up” portions of the landscape that can provide the highest ecosystem-services returns.

“If you badly need flood-control or storm-surge protection, where do you make your investment to have the highest payoff?” Daily asks. “We have a very quantitative approach that lays out, in biophysical terms, what you would get if you invested in the lit-up part of the landscape.”

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, meanwhile, has partnered with a competing effort, based at the University of Vermont’s Gund Institute for Ecological Economics, which Robert Costanza heads. There, a team is developing an analytical tool called MIMES, for Multi-scale Integrated Models of Ecosystem Services.

But such tools are just a start, Daily says, and it’s not enough to simply quantify the value of the ecosystem services that a particular piece of land provides. “You have to figure out a way of letting people realize those values and actually get paid to supply ecosystem services,” she says, “the way they get paid to grow food.”

That means creating some sort of market in which ecosystem services can be bought and sold — a market that, in its most highly developed form, might look similar to commodities markets for crops like corn and soybeans. Broadly, the concept goes by the name “payments for ecosystem services,” or PES, though such schemes have been proposed under a variety of different titles. The advocacy group Environmental Defense, for instance, refers to them as conservation incentives; they’ve also been called “green payments” in the context of various Farm Bill programs.

Daily and many others point out that ecosystem-services payments can meld human development and natural protection —particularly in poorer countries, where there may not be many options besides, for instance, cutting down all the trees on your land and selling them to a lumber mill.

Indeed, one of the most widely cited success stories for ecosystem-services payments is Costa Rica’s Pagos por Servicios Ambientales, or Payments for Environmental Services. In 1997, that country began signing five-year contracts with landowners who help sequester carbon, maintain water quality and protect biodiversity and the scenic beauty on which ecotourism is dependent — primarily by practicing sustainable forestry on their land. China, as well, has established a massive new program that, at least in one variation, provides grain to farmers who would otherwise hack cropland from heavily forested slopes and unleash eroded sediment into streams and rivers below.

But the largest, longest-running ecosystem-services payment program on the planet is the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Conservation Reserve Program. In the wake of the Dust Bowl, the government began paying farmers not to farm poor, erodible land. The program has ebbed and waned ever since, spawning several variants that pay farmers to preserve certain types of wildlife habitat on their lands and not to drain and farm important wetlands. Today, the program covers about 35 million acres of land in the U.S. at a cost of $1.8 billion.

Many observers say that ecosystem-services payments can attain an even-more-evolved state of being. The latest twist is “stacking” multiple services — and payments for them — together on a single parcel of land.

Ralph Heimlich is a former deputy director of the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service who now runs a consulting firm called Agricultural Conservation Economics.

“There’s only so much money you can attract to golden-cheeked warbler conservation,” Heimlich says, referring to an endangered Texas bird. “But if you can stack that on top of whitetail deer hunting, on top of reducing (fertilizer) runoff to the Guadalupe Reservoir, you have a bigger pool of bucks to work with.

“There’s a private market for carbon. In certain places, there’s going to be a private market for water. There are markets for specific kinds of wildlife habitat — for pheasants or endangered species,” he says. “The trick is to think of them as all saleable commodities so you can grow a long meadow rotation and get corn, soybeans, hay and carbon and wildlife, and you can conserve water, and you can reduce nutrient pollution to a nearby stream.”

Heimlich is as quick as anyone to acknowledge criticisms of payments for ecosystem services. But, he says, the concept has — at least to some degree — a rustic antecedent.

“In some sense, it’s actually an old model,” he says. “A farm is more than cropland: Most farmers have some woodland and some meadow and pastures and maybe even some native grassland. And originally, it was a portfolio-optimization decision as to what to plow, what to leave and what to harvest as timber. This is just a more complicated version of that.”

While efforts like the Natural Capital Project have pressed forward, some critics have greeted the notion of paying for ecosystem services with outright derision — albeit largely confined to the literature of academia.

The most acerbic critic is Mark Sagoff, an environmental ethicist at the University of Maryland. “The force of gravity is what keeps us all from floating into space,” Sagoff says, “but it’s free. Its value, in the sense of how much it benefits us, has nothing to do with its price.”

In the wake of the much-publicized collapse of honeybee populations and amid fears of an impending pollination crisis, insect pollination has become a particularly mediagenic example of the importance and value of ecosystem services. But Sagoff isn’t buying it: “We couldn’t have wine without wind because grapes are self-pollinated — but does that mean we want to put a price on wind?”

Earlier this year, in a paper published in the journal Environmental Values, Sagoff — who concedes that he’s made himself “a pariah” because of the stridency of his criticisms of ecosystem services — mercilessly deconstructed the honeybee example. “Ecological economists view the work of the insectival classes (along with that of nature’s other servitors) as Marxist economists regard the work of the labouring classes,” he wrote. “Both the insect worker and the human worker, on this general approach, produce … the surplus value that accrues to the capitalist but is truly earned by the labouring masses (in this instance, of insects). The sentimentally appealing but intellectually empty effort to ascribe economic value to nature’s services may at bottom constitute little more than the labour theory of value redivivus.

“Marx,” Sagoff continued, “had a recommendation: [T]he workers of the world should unite to throw off their chains. What recommendation do ecological economists offer the labouring insectival classes?”

Sagoff may be a singularly bombastic critic of the ecosystem-services concept, but he is not alone. David Ehrenfeld, the Rutgers biologist perhaps best known for his 1978 book, The Arrogance of Humanism, has long championed a purely moral rationale for conservation in the face of “utilitarian” views of nature. “I’ve been in a running battle with people who say you’ve got to save the Amazon because (it may hold) a cure for cancer — or baldness,” he says. “I’ve been fighting that battle for a long, long time.

“The mind-set that pushes ecosystem services is the same mind-set that has caused the need for conservation in the first place, that sees nature as something to exploit. It’s an exploitative approach. We save nature because it’s good for us.”

And, Ehrenfeld says, the environment is something beyond economics. “There is more to the environment,” he says, “than economics can ever express.”

There are other moral dimensions to the issue. John Echeverria is the director of the Environmental Law & Policy Institute at Georgetown University. He has written extensively about the two main competing ways to protect nature — through outright government regulation or by paying landowners to do what’s best for the environment — and he has warned that payments can erode a societal sense of environmental responsibility.

“It’s one thing to value ecosystem services,” Echeverria says. “It’s another to say, ‘And, the public ought to pay to preserve them.’

“It’s one thing to pay people in Borneo. It’s another thing to pay Weyerhaeuser.”

That, in fact, points to yet another twist in the debate. In the U.S. in particular, the notion of environmental ethics has a long history that, in this instance, traces back most directly to Aldo Leopold. Leopold wrote about a “land ethic,” or what has also been referred to as a “duty of care” for landowners.

And — as Eric Freyfogle, a University of Illinois law professor, has pointed out — Leopold wrote: “The average citizen, especially the landowner, has an obligation to manage his land in the interest of the community, as well as his own interest. The fallacious doctrine that government must subsidize all conservation not immediately profitable for the private landowner will ultimately bankrupt either the treasury or the land or both.”

Echeverria says that payments for ecosystem services not only undermine the land ethic but also play into the hands of the property rights movement. “A payment approach sends the message that you’re entitled to whatever you can get from the public, and you can do whatever you want with your land, the public and your neighbors be damned,” he says. “The more widespread payments program(s) become, the louder that message is.”

(Sagoff puts it a little more pungently: “The thing becomes completely corrupt as every single person who might be able to control carbon by farting less demands a credit.”)

All of that raises the possibility that widespread payments for ecosystem services will open a Pandora’s box: Incentives for conservation could actually become perverse incentives, and farmers, for instance, may farm in eco-friendly ways only if someone pays them to do it. In a 2005 law review article, Echeverria considered the “risk that repeated efforts to resolve land conflicts with the handy lubricant of public money could eventually convert environmental protection into a hostage beyond the reach of our elected representatives in any way other than paying for it.”

Environmental economists have themselves vividly described the phenomenon in the literature as “ransom behavior.” Echoing a sentiment expressed by others, Duke University professor of law and environmental policy James Salzman put it this way: “One might argue that farmers should not be paid to reduce their water pollution any more than I should be paid to stop mugging people.”

Even economically — and morally — rational behavior can lead to the same sort of problems as ransom behavior. In fact, the Department of Agriculture’s Conservation Reserve Program may well be Exhibit A. Rising commodity prices — particularly for corn, driven in large part by the exploding demand from new ethanol refineries and by this summer’s Midwest flooding — is putting serious strain on the program.

Farmers who enroll and agree to idle their land sign 10-year contracts, but a consortium of agribusinesses and Sen. Charles Grassley, R-Iowa, have been lobbying for Agriculture Department Secretary Ed Schafer to allow farmers to leave the program early, with no penalties. If Schafer agrees, it would effectively torpedo the whole point of the program.

Daily concedes that gaming the system is a genuine concern — and one doomily portended by the appearance of books with titles like Green Wealth: How to Turn Useless Land Into Moneymaking Assets (and Save the World). In fact, she says, she’s seen the gaming — literally — firsthand.

One staple at ecosystem-services conferences consists of role-playing exercises designed to simulate ecosystem markets. “Invariably, people figure out how to manipulate the system to their advantage,” Daily says. “I don’t have a magical answer there.”

But her position is, nonetheless, rooted in a tough-minded sort of pragmatism. “The ethical argument only goes so far when there’s such intense pressure on nature as there is today, and if we cling to traditional approaches alone, we’re dooming ourselves,” Daily says. “There are ethical reasons to destroy forests, too — like to feed your children.”

Costanza has weathered plenty of criticism for suggesting that a price can be put on nature, or at least on her constituent components. “People are in a certain state of denial about that,” he says. “The analogy is that of human life: People say you can’t put a value on that, but we do it all the time — implicitly, in the decisions we make.” Federal highway safety standards, for example, are based on a tradeoff between the value of a statistical life and the increased cost that would come with building safer bridges and installing more guardrails alongside highways. “It’s not like we value an individual life; we value a statistical life,” Costanza says. “We don’t know who it’s going to be.”

Costanza says people are constantly making the same kinds of tradeoffs with the environment, whether they think about them or not. Elsewhere, he has written, “The decisions we make as a society about ecosystems imply valuations. … I believe that society can make better choices about ecosystems if the valuation issue is made as explicit as possible.”

Among the many questions being raised about ecosystem services, one, in particular, has barely been addressed. Ecosystem services are clearly a product — but will there be a buyer? That, after all, is what it will take to make the concept really go. Costa Rica’s Pagos por Servicios Ambientales, for instance, has primarily been funded by a large World Bank loan, rather than a true market in which Costa Ricans who benefit from, say, clean water pay landowners who sustainably manage their upstream forests.

In the U.S., nothing will do more to turn ecosystem services into widespread reality than a cap-and-trade framework for greenhouse gases. This year’s Climate Security Act, sponsored by Joe Lieberman, I-Conn., and John Warner, R-Va., would have established such a system. Even though it failed to pass this year, there is growing consensus that a similar climate law is not far off. But if a cap-and-trade system for carbon would certainly bring lots of money into the mix, it’s far less clear where the deep pools of money will be found to pay for other ecosystem services like pollination.

For all the moralizing surrounding the notion of ecosystem services, however, an interesting hybrid approach is emerging. “The Europeans,” Ralph Heimlich says, “have a stoplight analogy. The red part is: Here’s some things you can do to your land that are so bad” — say, dumping leaking car batteries in prime golden-cheeked warbler habitat — “that we’re gonna take you to prison.

“The yellow light is: Here’s some things you can do and get away with, but we’re not happy about it, or here’s some minimal stuff that you really ought to do.

“Then the green light is: Here’s some stuff that’s above and beyond the stewardship obligation, and we’re going to pay you for doing it, because it’s to the benefit of society.”

The idea makes intuitive sense, and it seems an elegant fusion of the two doctrines: It suggests that there is at least a basic duty of care, some minimal land ethic. It also suggests that the public (or someone) might be well served by financially encouraging an improvement over the ecological status quo — whether the payoff comes in the form of carbon credits or tax write-offs or good PR.

From a public policy perspective, the stoplight model seems promising, but to become reality, it will require real public involvement. “The average Joe Citizen doesn’t know he’s being affected by this stuff,” Heimlich says. “He knows the bay is dirty, or he knows he got flooded out, but he doesn’t really understand why.

“The guys who really understand it are the guys who are either going to pay or get paid. And they’ve got the time and the interest, and they’re there in the halls of Congress.”

Sign up for our free e-newsletter.

Are you on Facebook? Click here to become our fan.