When she first heard about the organ thieves, the anthropologist Nancy Scheper-Hughes was doing fieldwork in northeastern Brazil. It was 1987, and a rumor circulating around the shantytown of Alto do Cruzeiro, overlooking the town of Timbaúba, in a sugarcane farming region of Pernambuco, told of foreigners who traveled the dirt roads in yellow vans, looking for unattended children to snatch up and kill for their transplantable organs. Later, it was said, the children’s bodies would turn up in roadside ditches or in hospital dumpsters.

Scheper-Hughes, then an up-and-coming professor at the University of California-Berkeley, had good reason to be skeptical. As part of her study of poverty and motherhood in the shantytown, she had interviewed the area’s coffin makers and the government clerks who kept the death records. The rate of child mortality there was appalling, but surgically eviscerated bodies were nowhere to be found. “Bah, these are stories invented by the poor and illiterate,” the manager of the municipal cemetery told her.

And yet, while Scheper-Hughes doubted the literal truth of the tales, she was unwilling to dismiss the rumors. She subscribed to an academic school of thought that swore off imposing Western notions of absolute or objective truth. As much as she wanted to show solidarity with the beliefs of her sources, she struggled with how to present the rumors in her 1992 book, Death Without Weeping: The Violence of Everyday Life in Brazil.

In the end, she argued that the organ stealing stories could only be understood in light of all the bodily threats faced by this impoverished population. In addition to pervasive hunger and thirst, the locals also faced mistreatment at the hands of employers, the military, and law enforcement. The medical care available, she suggested, often did more harm than good. Local health care workers and pharmacists gave the malnourished and chronically ill locals the catchall diagnosis of nervos and prescribed tranquilizers, sleeping pills, vitamins, and elixirs. The locals were well aware that wealthier people in their country and abroad had access to better medical care—including exotic procedures like tissue and organ transplants.

“The people of the Alto can all too easily imagine that their bodies may be eyed longingly as a reservoir of spare parts by those with money,” Scheper-Hughes wrote in Death Without Weeping. The stories of transplant teams murdering local children and harvesting their organs persisted, she wrote, “because the ‘misinformed’ shantytown residents are onto something. They are on the right track and are refusing to give up on their intuitive sense that something is seriously amiss.” The book, which was widely praised and nominated for the National Book Critics Circle Award, solidified her reputation as one of the leading anthropologists of her generation.

In 1995, Scheper-Hughes was the sole anthropologist invited to speak at a medical conference on the practice of organ trafficking held in Bellagio, Italy. Although there remained no solid evidence that people were being murdered for viable organs, rumors similar to the ones Scheper-Hughes had documented in Brazil had now spread from South America to Sweden, Italy, Romania, and Albania. In France, one popular story told of children being abducted from Euro Disney for their kidneys. The conference organizers asked Scheper-Hughes to explain the persistence of this gruesome meme.

The trade in kidneys particularly fascinated her. Unlike the trade in heart valves or corneas, kidneys were being shipped from country to country inside the living bodies of sentient individuals.

If the other participants at the conference, who were mainly transplant surgeons, were hoping to learn from Scheper-Hughes what was factual and what was false among these rumors, they were likely disappointed. She told them the stories were “true at that indeterminate level between fact and metaphor,” as she’d later write. Looking back, she feels certain that the surgeons—whom she thinks of as bright and skilled, like fighter pilots, but not very intellectual—didn’t really understand her more theoretical analyses. “We were speaking different languages,” she told me.

Still, Scheper-Hughes made the best of her time among the doctors. In Bellagio, she decided to do some on-the-fly ethnographic research into the current practices of transplant surgeons. As she spoke with them during boat rides on Lake Como or while touring the olive groves of Villa Serbelloni, the doctors answered her questions candidly. One surgeon told her that he knew of patients who had traveled to India to purchase kidneys. She remembers an Israeli surgeon telling her that Palestinian laborers were “very generous” with their kidneys, and often donated to strangers in exchange for “a small honorarium.” A heart surgeon from Eastern Europe admitted his concern that medical tourism would encourage doctors from his country to harvest organs from brain-dead donors who were “not quite as dead as we might like them to be.” In these new practices, Scheper-Hughes began to understand, human organs and tissue generally moved from south to north, from the poor to the rich, and from brown-skinned to lighter-skinned people.

While none of the surgeons’ accounts confirmed the kidnapping-for-organs rumors, Scheper-Hughes came to believe that the “really real” traffic in human body parts, as she has called it, was ripe for further study. “There were so many unanswered questions,” she recalls. “How were patients finding out about available organs in other countries? Who were the poor people who were selling their body parts? Nobody had gone into the trenches to find out.”

Scheper-Hughes’ investigation of the organ trade would be a test case for a new kind of anthropology. This would be the study not of an isolated, exotic culture, but of a globalized, interconnected black market—one that crossed classes, cultures, and borders, linking impoverished paid donors to the highest-status individuals and institutions in the modern world. For Scheper-Hughes, the project presented an opportunity to show how an anthropologist could have a meaningful, real-time, and forceful impact on an ongoing injustice. “There is a joke in our discipline that goes, ‘If you want to keep something a secret, publish it in an anthropology journal,’” she once told me. “We are perceived as benign, amusing characters.” Scheper-Hughes had grander ambitions. She decided it was time, as she puts it, to stop following the rumors and start following bodies.

IN HER WRITING, SCHEPER-Hughes has described her years of research into the international black market for organs as a disorienting “descent into Hades.” When she discusses the topic in person, she is animated and energetic. At 69, Scheper-Hughes presents a brassy mix of grandmother and urban hipster. On the winter day when I visited her home near the U.C. Berkeley campus, her hair was short, spiked, and highlighted with streaks of magenta, and she wore a short-sleeved shirt that revealed a stylized tattoo of a turtle—a gift, she said, from her son for her 60th birthday. As she talked about her dozens of international journeys to interview surgeons, donors, recipients, and various intermediaries, she showed me her office, which had formerly been the home’s garage. Inside were thousands of files, stored in dozens of large plastic bins and black file cabinets, along with drawers full of cassette tapes and field notebooks.

Since the mid-1990s, Scheper-Hughes has published some 50 articles and book chapters about the organ trade, and she is currently in the process of synthesizing that material into a book, tentatively titled A World Cut in Two. Over the years, she has had an outsize impact on the intellectual trends in her field, and her study of the organ trade is likely to be her last major statement on the meaning and value of the discipline to which she has devoted her life. Whether this body of work represents a triumph of anthropological research or a cautionary tale about scholarly vigilantism is already a hotly disputed question among her colleagues.

When Scheper-Hughes began to focus on the organ trade in the 1990s, she was a leading voice in a contentious debate about the future of anthropology, which was then in the midst of a long-brewing identity crisis. In the 1940s and 1950s, anthropologists had carried the banner of science into the field. Back in those days, a graduate student heading out to complete an ethnography of some far-flung people could be expected to carry with him a copy of George Murdock’s Outline of Cultural Materials, which lists more than 500 categories, cultural institutions, and behaviors under headings like “family,” “religious practices,” “agriculture,” and so on. Anthropologists were expected to document kinship relations and answer straightforward questions like: How is food stored and preserved? Are farm crops grown for animal fodder? Does the groom move in with the bride’s family after marriage, or vice versa? Because everyone was collecting the same types of information, the data could be replicated and updated, and cultures large and small could be classified and compared. Anthropologists of the era sought to create a taxonomy of human social behavior, and the doggedness and objectivity of the researcher were prized.

Scholars who came of age in the political tumult of the 1960s rejected this model. Scheper-Hughes was among a cohort of anthropologists who suggested that the scientific, taxonomic approach was just imperialism in another form, and that any claims of objectivity or literal truth were ultimately illusory or, worse, an excuse for exploitation and violence.

Nancy Scheper-Hughes. (Photo: Alfredo Srur)

Of course, there remained a question: If not just collecting and cataloging facts about other cultures, what should anthropologists be doing? In a 1995 debate with the anthropologist Roy D’Andrade in the pages of Current Anthropology, Scheper-Hughes argued for what she called a “militant anthropology,” in which practitioners would become traitors to their class and nation by joining political battles arm in arm with their subjects. The job of the anthropologist wasn’t simply to document the quotidian but to strip away appearances and reveal the hidden forces and ideologies that leave people dominated and oppressed. To do this, she suggested throwing off the traditional guise of the academic—in “the spirit of the Brazilian ‘carnavalesque’”—and joining the powerless in their fight against bourgeois institutions like hospitals and universities.

“The new cadre of ‘barefoot anthropologists’ that I envision,” she wrote, “must become alarmists and shock troopers—the producers of politically complicated and morally demanding texts and images capable of sinking through the layers of acceptance, complicity, and bad faith that allow the suffering and the deaths to continue.”

D’Andrade and others saw grave danger for the discipline in Scheper-Hughes’ call to the barricades (or to the carnival). D’Andrade believed that Scheper-Hughes and her intellectual allies were leading the field away from an objective science and toward what he called a “moral model” based on the simplistic duality of the oppressed and the oppressor. Her militant style of anthropology, he feared, would turn a once promising discipline into an exercise in “moralistic pamphleteering.”

“With the moral model, the truth ain’t exactly the thing that everyone strives for,” D’Andrade, who is now retired and living in Northern California, told me. “What you strive for is a denunciation of a real evil.” I asked him who prevailed in his public debate with Scheper-Hughes. “I believed that after the kerfuffle that people would get back to asking, ‘How do you know something is true or not?’ But in the end, the moral model swept the country and cultural anthropology stopped being anything that a self-respecting social scientist would call a science. The hegemony of the Scheper-Hughes position became total.”

Another loose consensus that emerged out of the debates of the 1990s was a widely shared belief that cultural anthropology’s focus on far-away, exotic societies had run its course: Why shouldn’t anthropologists turn their gaze on institutions that have real power in the modern world—banks, multinational corporations, courts, and governmental agencies? Or, for that matter, transplant units in major hospitals?

At the time, there were only a handful of papers in the medical literature addressing the rise of the global organ market. Since the 1970s, live organ transplants had changed from experimental procedures to a common practice in the United States, most European and Asian countries, half a dozen South American nations, and four countries in Africa. In 1983, the introduction of the immunosuppressant drug cyclosporine dramatically increased the potential donor pool for any given patient. By the mid-1990s, there were hints in the medical literature of the rise of a new phenomenon: transplant tourism. In 1989, a small article had appeared in The Lancet reporting an inquiry into allegations that four Turks had been brought to Humana Hospital Wellington, in London, to sell their kidneys. Other research suggested that the selling of kidneys from living donors was rapidly growing in India, and that in China human organs were being harvested from the bodies of executed prisoners.

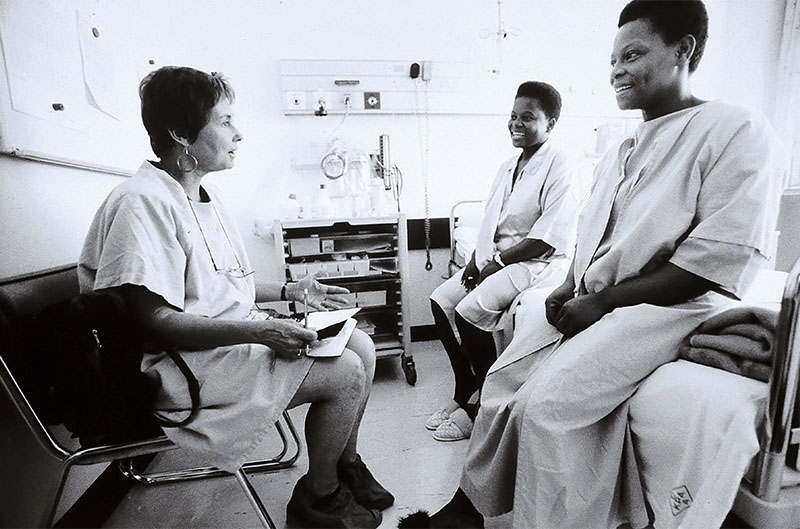

THE ORGAN RECRUITS: Scheper-Hughes found that Brazilians—often men trying to support families—were being trafficked to South Africa to sell their kidneys to patients from third countries. Alberty da Silva (pictured) contributed an organ to a woman from Brooklyn. (Photo: Organs Watch)

While most governments and international medical associations condemned the sale of human organs, laws and professional guidelines were inconsistent and often poorly enforced. What was clear was that the demand for organs outstripped the supply in nearly every country. In the United States, despite significant public outreach campaigns to encourage donations, there were already more than 37,000 people on organ waiting lists. Each year 10 percent of patients waiting for a heart transplant died before a donated organ could become available.

Scheper-Hughes’ research into the organ trade began in earnest not long after the Bellagio conference, when she teamed up with the event’s organizer, a medical historian at Columbia University named David Rothman; his wife, Sheila, a professor of sociomedical sciences at Columbia; and Lawrence Cohen, a fellow anthropologist from U.C. Berkeley. The four decided to spread out across the globe, dividing up the burgeoning global hot spots for transplant tourism. The Rothmans would focus their research on China; Cohen would investigate India; and Scheper-Hughes would travel mainly to Brazil and South Africa.

The research got off to a swift start. During breaks from teaching in the late 1990s, Scheper-Hughes visited African and South American dialysis units, organ banks, police morgues, and hospitals to interview surgeons, pathologists, nephrologists, nurses, patient’s rights activists, and public officials. “It became like detective work,” she told me. “I used a simple snowballing technique. I’d go to a morgue or a transplant ward and I’d get one person to tell me something—and then ask, ‘Where do I go from here?’ I found it enormously satisfying to begin to put the pieces together.”

Her collaborators, too, quickly made headway. While reliable estimates of how many transplants were happening on the black market were difficult to come by, evidence that this market existed appeared nearly everywhere the collaborators looked. In India, Cohen found people selling their kidneys to private transplant clinics that catered to patients all over the world, despite a 1994 law that made such transactions illegal. Selling kidneys, he discovered, had become so common in India that some poor parents even talked of selling an organ to raise a dowry for a daughter. David Rothman, for his part, had become convinced that a Chinese anti-crime campaign was associated with a growing enterprise that sold organs from executed prisoners.

In both Brazil and South Africa, Scheper-Hughes discovered that the dead bodies of many poor people were harvested, without permission, for useful tissues—corneas, skin, heart valves—to be exported to wealthier countries. In São Paulo, she worked with a city council member who had been tracking illegal commerce in human tissue taken from the cadavers of indigents and nursing-home patients. He showed her documents suggesting that more than 30,000 pituitary glands had been shipped to the United States over a three-year period. In South Africa, the director of a research unit in a public medical school showed her documents approving the sale of heart valves to medical centers in Austria and Germany. She also discovered, at private medical centers in both Brazil and South Africa, that kidneys from live donors were being bought and sold.

In 1998, while Scheper-Hughes was still writing up her first major papers on her field research, she and her collaborators met at a Starbucks in Tokyo during a medical ethics conference to compare notes. The material they were turning up seemed so remarkable that they brainstormed starting an organization called Organs Watch, which would serve as a repository for information on global transplant activity and a center for future research. By 1999, they had secured a $230,000 grant from the Open Society Institute, along with a commitment from the University of California, to help create the new organization.

As she gathered more information on Rosenbaum and his ties to multiple American hospitals, Scheper-Hughes made another unusual decision for an anthropologist: She began to share her findings with U.S. law enforcement.

But the collaboration between the Rothmans and Scheper-Hughes was short-lived. Scheper-Hughes’ first major article on the organ trade, which she published in April 2000 in Current Anthropology, chronicled her findings in the morgues and hospitals in Brazil and South Africa; it was also so impassioned that it sounded, at times, like the setup for a horror movie. “Global capitalism and advanced biotechnology have together released new medically incited ‘tastes’ for human bodies, living and dead, for the skin and bones, flesh and blood, tissue, marrow, and genetic material of ‘the other,’” she wrote. She called organ and tissue transplant a “post-modern form of human sacrifice” and accused transplant surgeons of conspiring to invent an “artificially created need … for an ever-expanding sick, aging, and dying population.”

Some anthropologists saw the paper as groundbreaking. Elliott Leyton, of Memorial University of Newfoundland, wrote that the paper was nothing less than the “beginning of a long-awaited moral vindication of much of modern anthropology, lost for so long in the contemplation of its own navel.” Other anthropologists, however, felt that Scheper-Hughes played fast and loose with source identification, and that her writing came off more like muckraking journalism than anthropology.

To her collaborator David Rothman, Scheper-Hughes’ rhetoric didn’t seem like scholarship at all. He was particularly taken aback by her contention that doctors were intentionally creating the demand for transplants. Rothman remembers traveling with his wife (and co-collaborator) to Berkeley in November of 1999 to attend the public launch of Organs Watch. “When Sheila and I saw the website that had been created, we were—let me see if I can get the right word—disturbed,” Rothman said. “It was sensationalistic, emotive, and provocative, with pictures of bodies but no charts. We realized that we operated in very different ways from Nancy.” After a heated argument, the Rothmans cut ties with Scheper-Hughes and ended their work with Organs Watch. But Scheper-Hughes was just getting started.

AS SOON AS ORGANS Watch went public in 1999, Scheper-Hughes began to receive hundreds of leads through emails and phone calls from people who claimed behind-the-scenes knowledge of the tissue and organ trade. She began to personally track down many of the stories. “I was traveling in a blur, like a whirling dervish,” she said.

She also began to push what she acknowledged were the accepted ethical boundaries of anthropological research. On her trips, as she wrote in a 2006 paper published in the Annals of Transplantation, she sometimes posed as a patient seeking a transplant or as someone looking to purchase a kidney for a sick family member. On a visit to Turkey, she pretended to be shopping for a kidney for a sick husband at a flea market near a minibus station in Askaray, a poor immigrant neighborhood of Istanbul. She found an unemployed baker who said he was willing to sell one of his kidneys, and she went so far as to sit with him at a local cafe to negotiate a price. At other times, she wrote, she’d simply walk into hospitals or clinics to confront a surgeon or an administrator or to learn what she could from patients. When stopped or questioned by staff or security, she would identify herself as “Dr. Scheper-Hughes,” knowing that the questioner wouldn’t likely suspect that she was referring to her doctorate in anthropology. Faced with what she called an international “organs Mafia,” Scheper-Hughes argued in a 2009 article for Anthropology News that she had no choice but to abandon many accepted rules of her profession. “When one researches organized, structured and largely invisible violence,” she wrote, “there are times one must ask if it is more important to strictly follow a professional code or to intervene.”

Her research during this period yielded a wealth of information and insight into the illicit networks of organ brokers. The trade in kidneys particularly fascinated her. Unlike the trade in cadaveric heart valves or corneas, kidneys were being shipped from country to country inside the living bodies of sentient individuals. In the Philippines, kidney sellers she interviewed often pulled up their shirts, displaying their nephrectomy scars with evident pride. They spoke of the surgery as a sacrifice made for their families, and members of their community sometimes compared their abdominal incisions to the lance wounds Christ received on the cross. In Moldova, as she reported in a 2003 paper published in the Journal of Human Rights, people who had sold their kidneys were considered so morally and physically compromised that they were treated as social pariahs. “That son of a bitch left me an invalid,” one Moldovan paid donor said of his surgeon. Young Brazilian men who had been flown to South Africa to sell their kidneys described to Scheper-Hughes how the experience had gained them a pass into the world of tourism and medical marvels. One told her that his main regret was not having spent more time in the hospital. “There were clean sheets, hot showers, lots of food,” he recalled. As he recovered, he went down to the hospital courtyard and bought himself his first cappuccino. “It was like ambrosia,” he said. “I really felt like a big tourist.” In the end, some attested that they would make the deal again, and some regretted the decision. “They treated me OK until they got what they wanted,” another seller told her. “Then I was thrown away like garbage.”

In her travels, Scheper-Hughes was also able to develop some relationships with kidney brokers, the middlemen who sought out donors in poor countries and neighborhoods. One convicted broker, Gadalya “Gaddy” Tauber, gave her lengthy interviews while serving out his sentence in Henrique Dias military prison in Recife, Brazil. Tauber, she learned, had facilitated a trafficking scheme that sent poor Brazilians to a private medical center in South Africa to supply kidneys for Israeli transplant tourists. He employed a number of “kidney hunters,” some of whom were young men who had already donated their kidneys, to find new recruits. In the end, it wasn’t difficult. Once the first young men came back from surgery centers in South Africa showing off their thick rolls of cash, Tauber and his associates had more willing donors than they needed. They began to drop the price they offered to donors from $10,000 to $6,000 and then to $3,000, Scheper-Hughes reported in a 2007 profile of Tauber.

Scheper-Hughes’ portrayals of organ donors, recipients, and even brokers like Tauber show a great deal of nuance and empathy. At other times, however—particularly when she writes about transplant doctors, bioethicists, or members of the “transplant establishment”—her writing turns markedly more strident.

Nancy Scheper-Hughes. (Photo: Alfredo Srur)

“Transplant surgeons vie only with the Vatican and its cardinals with respect to their assumption of privilege, irrefutability and of a kind of ‘divine election’ that seems to place them above (or outside) the mundane laws that govern ordinary mortals,” she wrote in one article. “Like child-molesting priests among Catholic clergy, these outlaw surgeons are protected by the corporate transplant professionals hierarchy.”

As Scheper-Hughes began to present her findings to doctors and transplant professionals, she experienced a series of harsh rebuffs and rejections. She remembers being called a liar by a senior pathologist at a 1999 medical ethics meeting in Cape Town. In 2002, at a special meeting on organ trafficking in Bucharest, she was shouted down by delegates in the audience: “Who invited this person? Why should we believe this slander?”

Scheper-Hughes recounts these confrontations as proof that she was telling truths that those in the “transplant establishment” were unwilling to face. Her conclusion at the time, as she wrote me in an email, was that “nobody, absolutely nobody cares about this topic.” This suggestion, however, is somewhat hard to square with what was going on around her. A number of international meetings—events that Scheper-Hughes attended—had been called to address the growing illicit market in human organs and tissue, and they were producing unambiguous recommendations and declarations to curtail the trade. In October of 2000, the World Medical Association condemned the sale of human organs and tissue, and urged countries to adopt laws to prevent such abuses. The next month, the United Nations General Assembly adopted the Palermo protocols, which, among other things, defined coercive organ sales and coercive donation as a type of human trafficking.

Colleagues have suggested that, in large part, the medical establishment reacted negatively to Scheper-Hughes not because of her facts but because of her rhetorical style and penchant for confrontation. “I think it’s fair to say that Nancy has a suspicion, bordering on hostility, of the medical enterprise,” says David Rothman, her former collaborator. (“I have used strong language at times—a phrase like neo-cannibalism isn’t going to make me any friends,” Scheper-Hughes said after I related Rothman’s criticism. “This is how the interpretive anthropologist works. We work with language and subtext.”)

A few of Scheper-Hughes’ colleagues have told me that she seems to become most energized when embattled. And indeed, discomfiting members of the medical establishment—rather than cultivating a collegial influence among them—may have been her plan all along. Although she rejects Rothman’s contention that she is hostile to doctors, Scheper-Hughes has long argued that it is her job to investigate an insulated surgical profession prone to self-glorification. She felt obligated to challenge doctors who talked of “saving lives”—as if the benefits to organ recipients trumped all other concerns. She saw bioethicists who argued for a regulated market in kidneys as “handmaidens of free-market medicine.” And she likewise criticized tame, “clinically applied” medical anthropologists who work closely with doctors to provide the spoonful of cultural knowledge that helps the Western medicine go down.

Back in 1990, she argued that the job of a medical anthropologist was to question, even ridicule, Western medicine. “Let us play the court jester, that small, sometimes mocking, sometimes ironic, but always mischievous voice from the sidelines,” she wrote in a prominent journal. “To the young, up-and-coming medical anthropologist I would say: ‘Take off that white jacket, immediately! Hang it up, and put on the white face of the harlequin.’” She warned even then that there would be a cost to those who assumed such a contentious stance. If your goal was to gain the respect of doctors, or to avoid “derision within conventional academic circles,” she wrote, the work of the militant anthropologist was not for you.

“It became like detective work,” she told me. “I used a simple snowballing technique. I’d go to a morgue or a transplant ward and I’d get one person to tell me something—and then ask, ‘Where do i go from here?'”

IN THE EARLY 2000s, as she was trying to piece together a more complete picture of the brokers, kidney hunters, and networks that made up the international kidney trade, Scheper-Hughes made a breakthrough—one that appeared to connect the global organ market to major U.S. hospitals. Research informants in Israel had told her in the late 1990s that a man named Levy Izhak Rosenbaum was a big player in international “kidney matchmaking.” Then, a few years later, in the summer of 2002, Scheper-Hughes began receiving emails from a man asking for her help in extricating himself from an organization—called United Lifeline, and headed by Rosenbaum—that he described as “the link between Israel and the United States in the illegal kidney trafficking business.”

As she gathered more information on Rosenbaum and his ties to multiple American hospitals across the country, Scheper-Hughes took the information directly to the surgeons and the hospitals implicated. In 2002, she set up a meeting with the surgeons at Albert Einstein hospital in Philadelphia, so that she could confront them in person with what she was discovering about transplants there that had been arranged by Rosenbaum. “I was very nervous,” she recalls. “I was thinking, What am I doing being madam prosecutor? But I felt that if I was going to publish this material I needed to inform them.”

Around the same time, Scheper-Hughes also made another unusual decision for an anthropologist: She began to share her findings with U.S. law enforcement, including officials from the FBI, the Food and Drug Administration, and the State Department’s visa fraud unit. Her information appeared to spark little interest and less action. She recalls one particularly frustrating meeting with an agent from the FBI in 2003. “I could see that the guy’s mind was elsewhere,” she recounted. “He didn’t seem to understand that this was a major crime.” Frustrated, she found herself thinking, “Look, I can do this. Give me a badge and I’ll go make an arrest,” she told me.

Scheper-Hughes acknowledges that other anthropologists consider turning over information to law enforcement to be crossing an ethical line, but counters that, given what she was documenting, she was more than justified. “I don’t care if some anthropologists think that we have an absolute vow of secrecy to our subjects,” she told me. “I think that kind of purity stinks to high heaven.”

For Scheper-Hughes, the apparent disinterest of U.S. authorities stood in sharp contrast to her reception by law enforcement officials elsewhere. In 2004, she was invited to brief police investigators and state prosecutors in South Africa regarding their investigation into illegal transplants involving Brazilian donors at several prominent hospitals in Durban, Johannesburg, and Cape Town. She shared with a mustachioed police captain named Louis Helberg the names and contact information of brokers, surgeons, organ recipients, and donors in Brazil and Israel, as well as the names of hospitals she believed were involved in the trade. In return, Helberg gave Scheper-Hughes access to confiscated hospital files and billing records, which she helped sift through and decipher. With Scheper-Hughes’ help and advice, Helberg eventually retraced the steps of her international investigation, traveling to Brazil and Israel and meeting with many of her sources. As a result of the investigation, South Africa’s largest hospital group, Netcare, admitted to more than a hundred illegal transplants and agreed to pay substantial fines. The story, when it broke, was front-page news in South Africa. One nephrologist there pled guilty to 90 counts of contravening the country’s Human Tissue Act. Four other Netcare surgeons and two hospital staffers were charged with various offenses (although the charges were later dropped).

In the U.S., however, it wasn’t until the summer of 2009—some seven years after she began sharing her information with the FBI—that federal prosecutors called Scheper-Hughes to tell her they had arrested Rosenbaum. He had been swept up as a minor player in New Jersey’s largest-ever political corruption and money laundering sting, which included the arrest of 44 people. Now that they were building a case against Rosenbaum, federal prosecutors were finally very interested in Scheper-Hughes’ research, and they met with her on several occasions. She offered to testify at trial, but in October 2011 Rosenbaum pleaded guilty to brokering three illegal kidney transplants and conspiring to broker an illegal transplant.

So far, his is the only successful prosecution for organ trafficking under the 1984 National Organ Transplant Act. Scheper-Hughes had hoped that the Rosenbaum case would herald the beginning of many investigations and prosecutions, but it wasn’t to be. “Why is he standing alone in the Trenton courtroom?” she wrote me in an email after Rosenbaum pleaded guilty to conspiracy. “Where are the ones he conspired with?” Frustrated with the U.S. investigators’ seeming unwillingness to take these crimes seriously, open new prosecutions, or pursue the surgeons and hospitals without whom the organ trade could not function, Scheper-Hughes continued her own investigation.

ONE DAY IN JANUARY of 2012, Scheper-Hughes called me to say that she might be on the verge of another breakthrough: A retired doctor, formerly a transplant surgeon at a major East Coast hospital, had agreed to a face-to-face interview, and Scheper-Hughes invited me to come along to witness the encounter. She and I met at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, where she was spending the year working furiously to finish her book on the organ trade. She handed me the keys to drive: She gets anxious on highways, she said. She also gets claustrophobic on airplanes and in elevators, and has difficulty reading maps, she told me. After just a bit of traveling with her, I found the serial globe-trotting that has defined her professional life all the more remarkable.

THE ROVING SCHOLAR: In the late 1990s, Scheper-Hughes traveled widely in South America and Africa, interviewing surgeons, nurses, pathologists, workers at morgues, and public officials to piece together an early picture of the organ trade. (Photo: Viviane Moos)

As night fell, we arrived at a Holiday Inn. The retired surgeon, a dapper man, met us in the hotel bar. Scheper-Hughes called the waitress over, asked her to lower the volume of the basketball game, and encouraged the doctor to order a drink. She then asked him open-ended questions about his personal and professional history. Her body language was friendly and intimate. She laughed at his jokes and shook her head empathetically at his stories of battling hospital bureaucracy.

The surgeon volunteered that he had conducted transplants later revealed to have been set up by Rosenbaum, but said that he had no direct knowledge that the donors had been paid. “In the back of my mind there is always the possibility that there is some incentive, but you can’t control it. Personally, I don’t see anything wrong with it.” Then he added: “I know it is illegal. We have a protocol.”

Scheper-Hughes then told him that others had fingered him as the ringleader. “You have been identified … as having been the person who set this whole thing up,” she said, referring to the Rosenbaum-brokered transplants. “I have to tell you that. I didn’t believe it, but that is what they said. You were accused of being the one who set it all up.”

“I didn’t set anything up,” he said, shaking his head. Alternatively cajoling and asking pointed questions, Scheper-Hughes pressed on. The doctor said that some of the transplants set up by Rosenbaum seemed “fishy.” “Some of the recipients were from New York, and it did feel a little strange that they found this donor from Israel.” He went on to suggest that it was likely that everyone involved at the hospital had good reason to be suspicious. “There is no question that everyone in the program felt that it would be very possible that there was some kind of incentive there. I didn’t feel that I had to be the police. As long as I don’t know and as long as I don’t have any evidence, I’m not going to deny the transplant just because I have the suspicion,” he said.

Scheper-Hughes had heard that same argument from surgeons around the world, and I could see her tensing up. When the surgeon suggested that all of his patients did well, her tone turned stern. “I want to tell you something,” she said. “Your patients didn’t all do so well—the donors didn’t all do well,” she said, adding, “There is no dependable aftercare. They go thousands of miles away and you don’t know what happened to them. So you don’t know who dies.” The doctor seemed momentarily chastened, but he maintained that he had improved the health of patients who needed transplants and that he had done nothing wrong.

The next week, Scheper-Hughes had a phone conversation with assistant U.S. attorney Mark McCarren, one of the lead investigators on the Rosenbaum case, and she shared some of the information she had gleaned from her meeting with the retired surgeon. McCarren told me that he was grateful for her help: “She had a lot more information than I needed. I don’t think there is any question that she has a lot of guts and courage in the way that she has pursued this issue.”

THE ACTIVIST: In Brazil, Scheper-Hughes testified about what she calls the “international organs mafia.” In public, she is often outspoken about what she regards as the medical establishment’s complicity in illegal trafficking. (Photo: Organs Watch)

Scheper-Hughes was less generous in describing McCarren’s efforts. She told me repeatedly that she was deeply concerned that McCarren and the prosecution team didn’t understand the full gravity of the crimes being committed. Why, she wanted to know, hadn’t prosecutors more aggressively investigated surgeons in the American hospitals connected to Rosenbaum? (Beyond what’s in court records, McCarren wouldn’t comment on who he included in his investigation.) After all, at the end of the day, Scheper-Hughes has told me on more than one occasion, it is the surgeons who hold the knives.

IN THE U.S., THE waiting list for a kidney now stretches past 100,000 people, while the rate of donations has remained relatively flat for the past decade or so. Recent data from the World Health Organization suggests that, in 2010, the 107,000 organ transplants carried out in the organization’s 95 member countries satisfied just 10 percent of the global need. The WHO estimates that one in 10 of all those transplanted organs was procured on the black market.

What impact Scheper-Hughes has had on transplant practices is an open question. Organs Watch still exists. Though she doesn’t have an office staff, Scheper-Hughes still trains graduate students and postdocs to do international fieldwork. The organization’s website contains only the following sentence: “The Organs Watch Web Site is currently under reconstruction and will be moved to a new address in August 2009.” Scheper-Hughes says she had to hurriedly take down the site after an organ broker told her she had been using information there to locate populations of the cheapest and most willing donors.

In anthropology, the kind of radical political advocacy and “militancy” that Scheper-Hughes championed in the 1990s has become less fashionable. “She is notorious in the field; she both attracts and alienates our professional colleagues,” says Arthur Kleinman, a prominent medical anthropologist at Harvard. “I admire her responsible, even blunt, honesty, but I’m troubled by her provocative and accusatory stances.”

She still has her fans in the discipline, among them the well-known anthropologist Paul Farmer. “The challenge she has taken up is: How can you be an advocate when everything is pulling you towards an ivory-tower model of disengagement?” he told me. “She is pushing the boundaries of social engagement, and she has gone beyond all parameters for an academic. She is doing what she and a lot of us think is right.”

In the medical community, despite her record of antagonization, many transplant surgeons give Scheper-Hughes credit for bringing widespread abuses to light, and for revealing the voices of donors and middlemen in the transplant trade. “She’s pointed out that underground illegal markets really do exist,” says Arthur Matas, the director of the Renal Transplant Program at the University of Minnesota. While most transplant surgeons like to think that their community would never participate in such a black market, Matas says, Scheper-Hughes has made it clear that they do—“sometimes unknowingly and sometimes knowingly.”

In the Philippines, kidney sellers she interviewed often pulled up their shirts, displaying their nephrectomy scars with evident pride.

By and large, however, Scheper-Hughes is still eyed warily by many in the transplant world, in part for glossing over what many see as critical degrees of culpability. Organ brokers like Rosenbaum can go to great lengths to make recruited donors seem legitimate to doctors, who may be fooled into proceeding with a transplant. “Participating knowingly and unknowingly are two different categories,” Matas says. “You have to be very careful when you cast wide blame.”

But in Scheper-Hughes’ view, surgeons either participate in illegal transplants with full volition, or they cultivate a willful blindness to their participation. As her writing shows, she prefers to focus on a larger thesis, which has not varied much since her time in northeastern Brazil: that Western medicine is often a weapon of violence used on the bodies of the poor or otherwise disempowered.

Rumors about people being murdered for their body parts still circulate in parts of the world. In 2009 a journalist named Donald Boström wrote an article in the Swedish newspaper Aftonbladet headlined “Our Sons Are Plundered of Their Organs.” The article suggested that Palestinian casualties in conflicts in the West Bank were being used as unwilling organ donors. Amid statistics about intense Israeli demand for kidneys and livers, Boström recounted that he had met “parents who told of how their sons had been deprived of organs before being killed.” The article caused an international rift between Sweden and Israel and was condemned as baseless “blood libel” by Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

Scheper-Hughes came to Boström’s defense in Counter-Punch, presenting what she called a “smoking gun” to back up the claims in his article. Her evidence was an interview she had conducted with an Israeli pathologist named Yehuda Hiss, the director of the the Abu Kabir Forensic Institute, Israel’s central facility for conducting autopsies. In the interview, which Scheper-Hughes had recorded in 2000 but had not previously written about, Hiss made the remarkable admission that his institute had, without family permission, taken corneas, skin, bone, and other tissues from the dead bodies of Palestinians, as well as from the dead bodies of Israel Defense Forces soldiers and other cadavers that came through his morgue. The organs and tissues were used for medical training and research, and for skin and cornea transplants. (After the tape was released, Hiss denied any wrongdoing.)

Scheper-Hughes’ interview with Hiss was a testament to her extraordinary knack for obtaining access to sensitive information and making an impact. Hiss has since been removed from his post at Abu Kabir. The repercussions of the controversy, legal and otherwise, will likely be felt for many years.

But given the extraordinary political tensions that persist between Israelis and Palestinians, this would seem to be a case where it’s especially important to clearly delineate rumors from facts. As horrifying as Hiss’ taped admissions were, they did not confirm the stories circulating among Palestinian families, and reported by Boström, that their sons’ organs were being harvested while the young men were still alive. In a 2013 essay about the controversy that she co-wrote with Boström, Scheper-Hughes criticized the international media for construing the Aftonbladet story as claiming that “Israeli soldiers were deliberately hunting young Palestinians in order to cut out their organs.” She wrote that this was a “distortion” of Boström’s reporting, one that distracted from the issue of transplant practices. While it’s true that the original article stops short of making precisely this claim about “hunting,” it does uncritically report the perception that Palestinian victims were still breathing when they disappeared from their villages. It’s not surprising that international audiences would find this a morally salient detail.

When I suggested that there seemed to be an important difference between the charges repeated in the Boström article and the revelations from her interview with Hiss about cadaveric tissue-harvesting, Scheper-Hughes became frustrated that I wasn’t seeing the big picture. “The distinctions you are making are just getting into obfuscation,” she said. “It is true that the dead don’t care what happens to their body—but the living do care. Those Palestinian families care. It isn’t that I don’t understand the difference.”

“Does my interview with Hiss support the Boström article? Absolutely. It’s not that different,” she said. “If you miss that point, you are missing what I’m all about. I care about the body, alive or dead. That is what medical anthropologists are good at. We’re guardians of the body.”

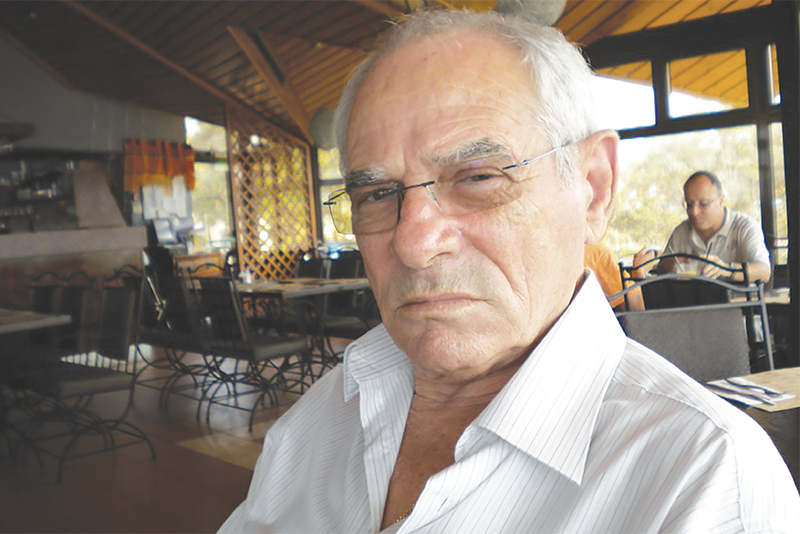

THE BROKER: Gadalya “Gaddy” Tauber described to Scheper-Hughes how he facilitated a trafficking scheme that sent poor Brazilians to clinics in South Africa to supply kidneys for Israeli transplant tourists. (Photo: Nancy Scheper-Hughes)

Other medical anthropologists, however, argue that Scheper-Hughes does not paint the world of the illegal organ trade in enough shades of gray. “She is not a scholar at heart,” Kleinman told me, “for good and bad. She always begins with a partisan position and a sensibility of outrage at injustices. She lumps rather than splits. The details of the argument are less important than the advocacy, the lobbying.”

IN THE SUMMER OF 2012, I met up with Scheper-Hughes on the steps of the federal courthouse in Trenton, New Jersey, for the sentencing hearing for Rosenbaum. In the fourth-floor courtroom, Scheper-Hughes took a seat in the front row where she could see Rosenbaum’s bearded and portly profile. Arguing for a stiff sentence, prosecutor McCarren called four witnesses. He questioned an administrator from Albert Einstein hospital and a surgeon who worked there while Rosenbaum was running his kidney trade business. He called to the stand a middle-aged woman named Beckie Cohen, who tearfully described how grateful she was that her family had been able to pay Rosenbaum $150,000 to arrange a kidney transplant in a Minneapolis hospital for her ailing father, Max Cohen. McCarren also questioned Elahn Quick, a young man born in Israel of American parents, who was paid about $25,000 to donate one of his kidneys to Mr. Cohen.

In describing his dealings with Rosenbaum, Quick told of no overt pressure or threats. In the end he said he felt used and somewhat victimized by the transaction, but he didn’t regret the operation. “I wanted to do something meaningful,” Quick said. “I’m still holding on to the fact that I saved a life.” At this point Scheper-Hughes leaned to me and said that this refrain about “saving a life” was bunk: “These people that get transplants are mostly just old.”

Scheper-Hughes spent most of the hearing rapidly writing in her notebook, but she made clear, in whispered asides, her disapproval of the proceedings. When the judge mentioned that she had been moved by the letters of support for Rosenbaum sent by recipients of organ transplants he had arranged, Scheper-Hughes sighed and said, “Oh, Jesus Christ.” When Beckie Cohen teared up recounting her family’s distress over her father’s illness, which led them to pay Rosenbaum to arrange for a kidney seller, Scheper-Hughes leaned to me and said: “She could have given him her kidney.” When a doctor from Albert Einstein hospital testified that he had no certain knowledge in the early 2000s that the donors were being paid by Rosenbaum, Scheper-Hughes whispered: “McCarren is not a very good questioner. I could do better.” During the course of the long hearing, Scheper-Hughes had a sharp comment for every player in the courtroom: the doctor, the donor, the recipient’s daughter, McCarren, the defense attorneys, and the judge. She had become, almost literally, the court jester she describes in her writing, a mocking, dissenting voice from the sidelines.

After the hearing, Scheper-Hughes and I had an early dinner at a nearby Cuban restaurant. She hadn’t eaten all day and her energy was flagging. She told me she was satisfied with the sentence Rosenbaum received at the end of the hearing—two and a half years in federal prison—but said that she hadn’t seen or heard anything that day that might change her perceptions of Rosenbaum or of the kidney trade that she had tracked to American shores.

I asked her about one scene described on the stand by Elahn Quick, the donor. Quick remembered that when he woke up after the operation, the family of Max Cohen had gathered around his hospital bed and applauded his sacrifice. I thought it was a poignant moment, one that suggested that Quick wasn’t just an anonymous donor to the Cohen family, but something more. Scheper-Hughes waved away the scene. “What I can’t stand is false emotion,” she said, reminding me that Quick ultimately felt betrayed and kicked aside. “It makes my hair stand up. I can smell it like a rat.”

This post originally appeared in the July/August 2014 print issue ofPacific Standardas “The Organ Detective.” Subscribe to our bimonthly magazine for more coverage of the science of society.