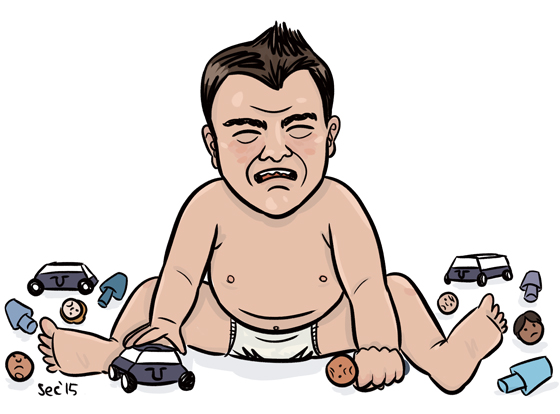

They did everything that Uber and its CEO Travis Kalanick didn’t do.

Night School aimed to provide late-night transit service between San Francisco and Oakland, supplementing the public bus and train services that provide intermittent, if any, service after midnight. The company would use the public school buses that sit unused in parking lots on the weekends, and charge $8 per ride or $15-20 per month for unlimited service (the price points fluctuated).

The school buses seemed a little twee, but the strategy was clear and smart. And it struck a nerve. Last May, Night School received a glut of positive media coverage ahead of its imminent launch. Two weeks later, it was postponed—the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) had become involved. The state agency, a target of much start-up ire, had previously attempted to fine and regulate Uber, Lyft, Sidecar, and others. At the end of 2014, Night School announced that it was no longer postponing the project—the founders were killing it.

Why were some private transit start-ups able not just to survive but thrive under current regulatory standards while Night School collapsed? And what does that mean for the future of start-up business in California?

For all of Uber’s bluster to appeal across classes—from “your own personal black car” to “we’re creating good working class jobs”—it might well not exist if public utilities worked well in San Francisco.

Dense residential swaths of the city are not served by regional BART trains or city Muni ones, and the local buses are notorious for running dramatically off schedule. The transit culture of the Bay Area is still one of reliance on personal vehicles. As the region absorbs tens of thousands of new tech-working residents with their high salaries and low tolerance for municipal dysfunction, this has only created more pressure. The BART worker strike of 2013 proved these politics clearly: Tech workers and even executives tweeted their frustration with a class of transit worker that makes, on average, a third less than the median software engineer.

It was in this climate that “rideshare” companies established their businesses and activists turned their sights on the tech commuter buses, which were also a result of industry outgrowing the public’s ability and willingness to keep apace. Every kind of transit has increased by several percentage points over the past two years in the Bay Area—trains, cars, and buses alike, some boasting double-digit growth in less than 12 months. Public services are straining to meet this new capacity, while traffic jams grow longer on the region’s highways.

Public services are hardly an unwitting victim in this arrangement: When BART was first planned, cities and counties across the region opted out, shrinking the scope of the system dramatically. It was never planned as an urban train network, but instead as a method of shuttling suburban workers to and from their 9-5 jobs in the city. Only one tube was installed under the bay between San Francisco and Oakland, and the train technology required that it be closed for several hours each night for maintenance.

For a region that would come to be known as the seat of American futurism, this was an astounding lack of foresight.

Uber, Lyft, et. al. established themselves not just because of the ubiquity of tech tools in the Bay Area, but also because of this lack of transit options. They asked state and local regulators for forgiveness, not for permission—if they even asked. They misrepresented themselves and their businesses as platforms instead of services. They pushed back by recruiting lobbyists both professional and crowd-sourced.

When it first came on the scene, Night School was often included in this new school of “sharing economy” transit start-ups “activating under-utilized resources.” Some of this was true. But it was fundamentally different.

For its fleet of vehicles, Night School relied on its partner First Student, the largest school bus operator in the United States. “Not following the rules was never an available option for us,” Night School co-founder Alex Kaufman says. “Even though First Student agreed with us that there was no legal problem with what we were doing, they felt they had no choice but to obey the CPUC so as not to jeopardize their whole operation.”

For the better part of 2014, Night School tried to work with the CPUC. Unlike Uber and Lyft, it was not a “platform,” and never described itself as such—it was a private bus service with professional, insured, licensed drivers, regulated vehicles, clear routes, and consistent fares. There would be only one originating and culminating stop each to start, each located in dense residential areas in San Francisco and Oakland respectively. The company planned to add more stops in the future. Buses would run approximately every half hour, with more service planned if and when demand increased.

Local media coverage framed the service as primarily aimed at late-night party-goers, but Kaufman told a reporter last year that “a lot of people get off work late and have no affordable way to get home—Night School could really service their needs.” He emphasized that Night School would run in a dense but underserved residential area—the Mission—while the overnight trans-bay buses that currently run hourly depart from the city’s downtown. BART train service currently shuts down between midnight and 6 a.m.

The response to Night School’s speculative press was overwhelmingly positive. But less than two weeks later, the week of its planned launch, Night School was postponed indefinitely while its founders grappled with the CPUC, which claimed the start-up was not properly licensed as a passenger carrier. If Night School had sought to operate as a service only available to members of a private club, the CPUC wouldn’t have had jurisdiction over the business. But the founders’ vision was decidedly public, from the school buses to the low fares.

The CPUC has struggled to codify new rules for “transportation network companies,” shifting and changing regulations over the last three years while those companies continued to operate. Night School never got the chance to open its doors.

After months of back and forth, false starts, and moved goal posts, Night School announced its closure last December. The company’s statement read in part:

Back in May we were on the verge of launching a service that would have greatly improved late-night transportation in the Bay. Then the CPUC got involved. Though they never raised any substantive objections to the safety or soundness of our plan, the CPUC’s actions have effectively made it impossible for us to launch. We have now decided to shut down the company and refund all memberships. … We are not seeking more money or lobbying for a change in laws. After spending much of the past year banging our heads against a wall of bureaucracy, we have reached a dead end.

The lack of public outcry over Night School’s troubles over the last several months suggests that fighting “over-regulation” of start-ups is less about principle and more about money. Companies without tremendous venture capital and influential lobbyists can’t afford to be disruptors; their struggles don’t even inspire political outrage.

It doesn’t seem insignificant that the CPUC allowed for high-priced private car services while shutting down the more modest Night School, which would have offered rides for as little as a couple dollars each to monthly members, maxing out at $8. Rather than suggesting Uber as an alternative, the shuttered start-up encouraged its former members to use the newly expanded late-night public bus service.

Where Night School hit a brick wall, Uber and Lyft have always found a road through. When the CPUC was keeping Night School from operating because of a license issue, the regulatory agency also warned ride-hailing companies not to launch new carpooling services, which allow individuals paying separate fares to share the same car ride. They did it anyway. They’re still doing it. They ran right over the CPUC, and they just kept going. More recently, the California Department of Motor Vehicles threatened more fines against ride-hail drivers who didn’t obtain commercial license plates—and then reversed its decision just one day later.

“For a while the CPUC loved us—’you guys are so much nicer than Uber!'” Kaufman says. “But in the end, it didn’t really help to play nice.”

On the public side, Bay Area agencies and legislators are meeting to come up with a plan for a second trans-bay tube to increase BART service. But experts say any such construction would take, at best, a decade or more. Though there is already a clear need, it will take huge culture and infrastructure changes to foster extensive, sustainable public transit networks across the Bay Area. Any private measures, Night School included, are a stop-gap.

Consumers are instead growing more and more comfortable with private ride-hailing culture. If and when they have ethical qualms, those don’t seem to be reflected in Uber’s profits. Over the last two years, much of the critique of Uber has focused on the company’s aggressive attitude toward local governments. The company’s approach hasn’t worked with many municipalities, more than a few of which have banned the service altogether.

California has claimed to do things differently, emphasizing the importance of a regulatory code while also celebrating “disruption” and providing leeway for new innovations to thrive. But this leeway isn’t given out equally. Of course, that’s the business theory of the Wild West: Whoever has the most gold wins.