On Sunday, Politico reported that Ivanka Trump, the president’s daughter and special adviser, and Senator Marco Rubio (R-Florida) have begun strategizing how best to advance a new paid family leave proposal. The reporting comes on the heels of President Donald Trump‘s State of the Union Speech, in which he specifically called for a national paid family leave policy.

At the moment, it seems unlikely the issue will get much attention this year. Congress is currently struggling with a number of more pressing issues—funding the government, raising the debt ceiling, stabilizing the ACA’s non-group markets, protecting Dreamers, and so forth.

Nonetheless, paid family leave is slowly but surely becoming something of a bipartisan issue as politicians recognize its effects on voters across the political spectrum. According to a report published last year by the Urban Institute, only 14 percent of American civilian workers had access to paid family leave through their employers in 2016. This makes the United States a prominent outlier among other developed, industrialized countries.

“[T]he United States is one of two countries that do not have a national paid leave policy to allow mothers to spend time caring for their newborn and regain their health after childbirth,” the report reads. “Almost all other countries provide paid maternity leave, and many countries also provide paid paternity leave and the guarantee that the parent can return to the same (or comparable) job.”

There are a number of different paid family leave proposals floating around Washington, D.C. Below, we’ve rounded up the most prominent ones.

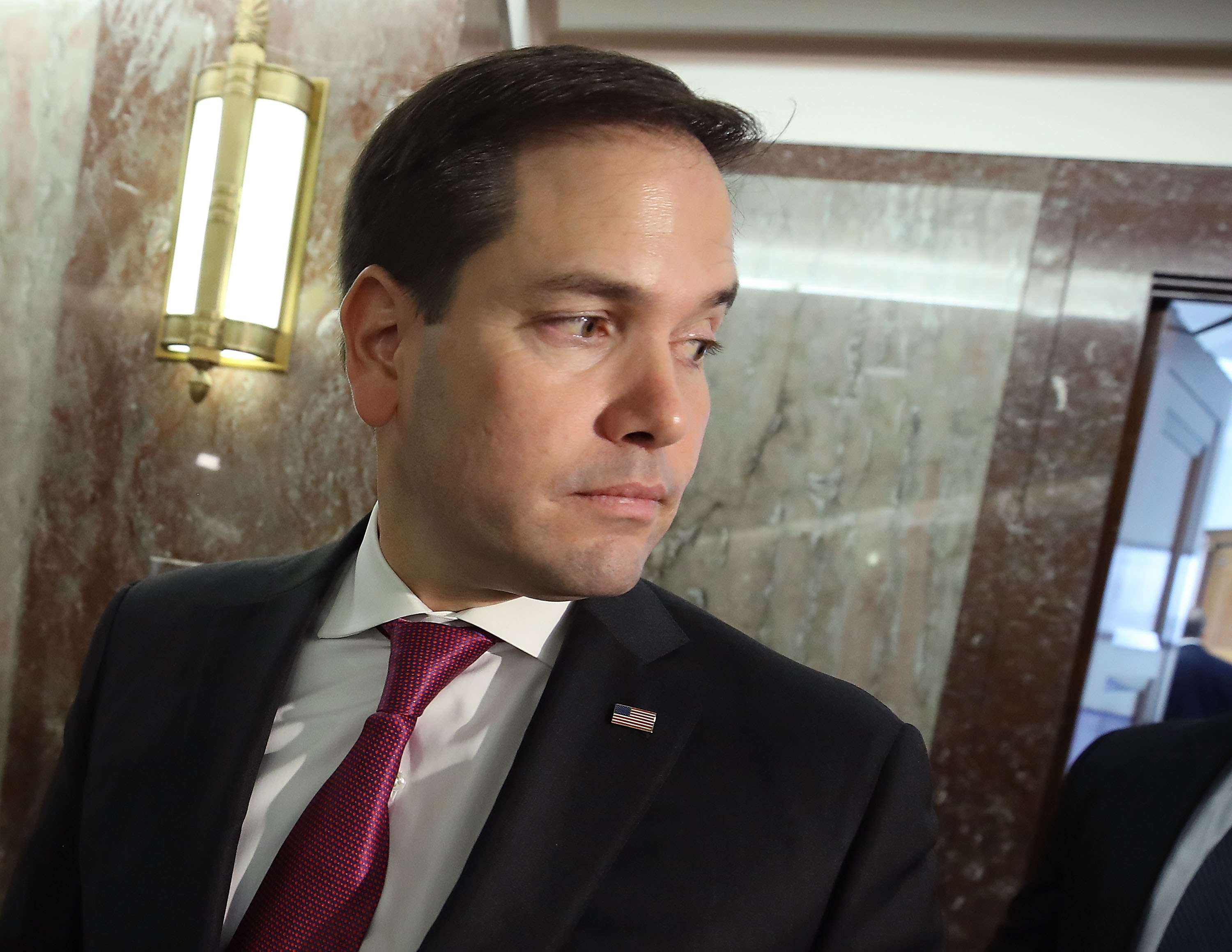

The New Rubio Plan

Politico reports that Rubio is considering a plan that would allow “people to draw Social Security benefits when they want to take time off for a new baby or other family related matters, and then delay their checks when they hit retirement age.” The details on this new proposal are sparse. We don’t yet know what the replacement wage (i.e. the percentage of their normal wages that people receive during leave) would be, or how much leave people would be permitted.

Pros: It wouldn’t raise taxes (which means it might be more likely to garner support from Republicans), and it would (presumably) be available to all workers, not just those at generous employers.

Cons: It potentially jeopardizes the retirement security of low- and middle-income workers who don’t have access to paid family leave through their employers. These workers are also both more likely than wealthier workers to be reliant on their social security benefits in retirement and may be the least well-suited to delay their retirement. Putting off retirement by six or 12 weeks may not seem onerous to a professor or a management consultant, but it could be very difficult for a retail worker or nursing assistant who must stand on their feet all day. The effects may be particularly pernicious for women, who still earn less than men (and so struggle more in retirement) and also are more likely to bear caregiving responsibilities.

“I think we shouldn’t force people, especially women, to choose between retirement security and their ability to care for families,” says Julie Kashen, a senior fellow at the Century Foundation who studies work-family policy.

The Trump (Budget) Proposal

In last year’s budget proposal, the Trump administration proposed a six-week paid leave policy for new parents, to be administered via state unemployment insurance (UI) programs. The details of how this new program would be funded were a bit hazy: The administration suggested some funding could come from reforms to the UI program, and that some states might also have to raise UI taxes.

(Photo: Chris Kleponis-Pool/Getty Images)

Pros: Six weeks is better than nothing. And the proposal would apply to both new mothers and fathers, an improvement over Trump’s campaign paid leave proposal, which applied only to new mothers.

Perhaps the biggest perk of this proposal, however, is that it heralded a shift in the political winds. “It was really encouraging to see both sides of the aisle talking about this and feeling like it’s a top tier issue,” says Wendy Chun-Hoon, the co-director of Family Values @ Work. “I think we’ve agreed as a country that the time has come.”

Cons: The proposal would not have covered non-parental caregivers. Most early childhood experts believe 12 weeks of parental leave, not six, is the bare minimum. It’s also not clear what the replacement wage would be under this program, but current rates for the UI program are quite low (around 40 percent) and would be insufficient for low-income families. The proposal also doesn’t seem to include job protections for those working at small employers and thus not covered by the Family and Medical Leave Act.

Critics were also concerned that a plan like this would put too much strain on already stressed state unemployment insurance programs. “I would love it if our unemployment insurance programs were solvent and secure, and when you lost your job, you knew you could count on this insurance program you had paid into,” Kashen says. “But the truth is there are way too many states whose UI programs are really at risk if we have an economic downturn … we don’t want to be choosing between people who’ve lost their job and people who just had a baby.”

The (Original) Rubio Proposal

During the 2016 presidential primary, Marco Rubio endorsed a plan from Senator Deb Fischer (R-Nebraska) to offer a tax credit to employers who offered paid parental leave to low-income parents. The GOP tax bill passed in December actually included just such a tax credit. Fischer says that she plans to track how effective the credit is.

Pros: It doesn’t require workers to pay higher payroll taxes. Republicans like it. It’s been signed into law.

Cons: Employers participate voluntarily, so there are no guaranteed protections for workers. Critics are also skeptical that it will do anything other than subsidize those employers who would have provided family leave even without the credit, thus worsening disparities between workers with generous employers and those without.

Last year, a joint working group of scholars from the Brookings Institution, a left-leaning think tank, and the American Enterprise Institute, a right-leaning think tank, produced a report on various paid family leave proposals. Here’s what the researchers had to say about tax credits:

[T]he biggest drawback of this tax-credit approach is that it would end up subsidizing firms that already offer paid leave. Such a policy might simply lead to substantial windfalls to employers with existing paid leave policies without expanding coverage to those most in need. The requirement that the GAO study its impacts before proceeding with a more extensive paid leave policy could be beneficial to understand firm behavior and employees’ leave-taking, but we are skeptical that this proposal would move the needle much on improving access to paid leave.

(Photo: Mark Wilson/Getty Images)

Chun-Hoon points out that employer-based credits also make less sense in a modern economy in which workers are much less likely to work for one company for their entire adult lives. “It really does little to acknowledge that workers are working for multiple employers over their lifetimes now, they’re moving in and out of bigger employers, smaller employers, etc.” she says. “All this does is reinforce an employee/employer old model kind of relationship. We need to solve the question of how all workers can pay into an insurance program and make sure that the benefit is not reliant on where they’re working at the time.”

The Democrats’ Proposal

Introduced by Senator Kirsten Gillibrand (D-New York) and Representative Rosa DeLauro (D-Connecticut), the FAMILY Act would provide 12 weeks of paid family leave for both new parents and other caregivers. The replacement wage would be set at 66 percent (and capped at $1,000 a week). The program would be funded by higher payroll taxes on both workers and employers and administered by a new department in the Social Security Administration. The legislation also includes some anti-retaliation job protection measures for workers not covered by FMLA.

Pros: It’s fairly generous, with respect to both amount of leave, replacement wage, and eligibility (covering both parents and other caregivers). It’s portable, so workers would have access to it no matter where they worked. And it has a stable, reliable funding stream. It was also designed with the lessons learned by state family leave programs in mind.

“The FAMILY Act is really a reflection of what the early states, like California and New Jersey have learned and done with their programs,” Chun-Hoon says. “The fact that it’s 12 weeks, that’s the bare minimum that early childhood experts believe is what’s needed for maternal and infant health. It goes beyond just the parental leave to really cover the full spectrum of the time that we need to care for not just a new baby, and the replacement wage is generous enough to allow low-income workers to take advantage of the program.”

(Photo: Zach Gibson/Getty Images)

Cons: It’s arguably expensive, although advocates argue that the average worker would see their payroll taxes go up by only $2 per week to cover the plan. It’s not clear if any Republicans will support it.

Speaking of the States

Five states—California, New Jersey, Rhode Island, New York, and Washington—and the District of Columbia have implemented paid family leave policies. The amount of guaranteed leave ranges from four weeks to 12 weeks. Similar to the FAMILY Act, all of the state-level programs are funded through increases in payroll taxes. The wage replacement rates vary from 50 percent to 70 percent in California (for low-income workers only).

Several other states are also expected to consider paid family leave proposals in 2018.