When passengers hear the cry of “All aboard!” they rarely give any thought to whether they will arrive safely at their destination. There have been many advances in railway safety, and, when compared with other means of transportation, the railroad safety record is stellar.

On Sept. 12, 2008, the 222 passengers who were riding Metrolink No. 111 from downtown Los Angeles to the Ventura County Moorpark train station probably felt that way. After all, the idea that those who were responsible for running the train could abandon all caution and fail to follow basic operating procedures, risking the lives of all on board, was unthinkable.

But engineer Robert Sanchez, who alone controlled the movement of No. 111, was completely absorbed in texting friends. He ran two red lights and failed to yield to the oncoming freight train using the same single track; his train smashed head-on into a Union Pacific freight train just outside the suburban Chatsworth station. He never even applied the brakes. The force of the collision shoved the locomotive straight into the first passenger car, derailing the rest of the train. Twenty-five people died, including Sanchez, and 135 people were injured in the mangled wreck. None of the crew aboard the Union Pacific train died.

Human error has been and remains a major, yet entirely avoidable, cause of some of the worst train wrecks in U.S. history.

Even back in the mid-19th century, two days after the Great Train Wreck of 1856, The New York Times ran an editorial that blamed the railroads and said that trains going in opposite directions should never share a single track.

Now, one year after the Metrolink catastrophe — and 152 years after the New York tragedy — laws have been passed, money has been allocated, and a few small changes have been made in operating procedures. But the one system that would have prevented this catastrophe, “positive train control,” known as PTC, will not be fully implemented before 2012. That is three years earlier than the Rail Safety Improvement Act of 2008, which mandates PTC on all passenger rails in the United States.

Is it really that simple? Policymakers say so.

In testimony at a California State Senate hearing on rail safety about a month after the crash, U.S. Sen. Dianne Feinstein said, “A technology called positive train control is in place on other rail systems to prevent human error from causing fatal disaster, but trains in California currently don’t have it. If positive train control had been in place on Metrolink on September 12th, I believe 25 people would still be alive today.”

A year later, in announcing the appropriation of funds for a new railroad safety program, her colleague Sen. Barbara Boxer was quoted in a release saying, “Facts revealed by the National Transportation Safety Board investigation indicated that PTC could have prevented the tragic crash of a Metrolink commuter train and a freight train in Chatsworth, California last year.”

In Development For Nearly A Century

The federal government in 1922 originally mandated some form of automatic train stopping, yet, to this day, many passenger and commuter lines are without any meaningful and effective form of protection from simple human error. Trains are legally permitted to remain without positive train control until Dec. 31, 2015, the deadline mandated in the Rail Safety Improvement Act of 2008.

According to the Federal Railroad Administration, PTC systems are “integrated command, control, communications and information systems for controlling train movements with safety, security, precision, and efficiency. PTC systems will improve railroad safety by significantly reducing the probability of collisions between trains,” danger to railway workers and derailments caused by excessive speed.

By utilizing the technology of global positioning satellites, PTC would automatically override dangerous train movements, remain continuously updated on train locations and stop a train if the crew was incapacitated. For the railroads, the agency writes, the benefits are “improved running time … higher asset utilization, and greater track capacity.”

And there are working systems out there. “Pilot versions of PTC were successfully tested a decade ago, but the systems were never deployed on a wide scale. Deployment of PTC on railroads is expected to begin in earnest later this decade.”

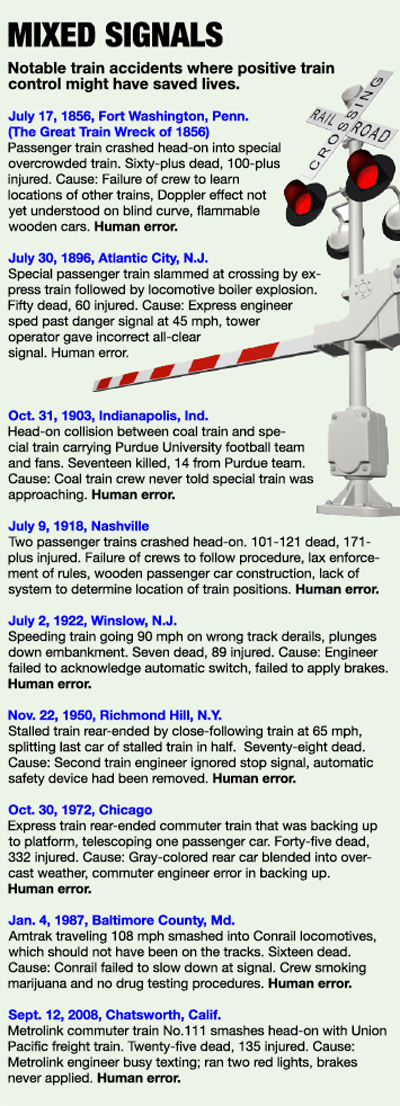

All of the train disasters cited in the sidebar, at right, could have been prevented by some system of automatic train control that would override human error. Given PTC’s benefits and track record, why is it taking so long for such a system to be installed and operating on all railroad tracks in the United States?

Wait Until 2015

There have been many different automatic train-stopping systems in existence going back to the early part of the 20th century. Europe has had a form of automatic train control operating in some countries, including Great Britain, Germany and France, since the 1930s.

Under the Transportation Act of 1920, the Interstate Commerce Commission required 49 railroads to have an operating train-stop or train-control system on at least a portion of their passenger train routes. What happened to keep that from coming to fruition?

In the 1980s, the Association of American Railroads developed detailed plans for an advanced train-control system using digital radio communication and microprocessor controls. And in 1987, the Burlington Northern Railroad in tandem with Rockwell International developed a similar system using GPS called Advanced Railroad Electronics System.

In 1991, teams from Harvard Business School twice studied the $350 million Burlington Northern system. The outsiders were enthusiastic — Harvard described their “zealous advocacy of the project” — that the system would save the freight hauler lots of money. But company executives at the then-cash-strapped company were leery about the actual savings and feared their traditional system couldn’t adapt to PTC.

Subsequent studies have back up the business case for PTC. The consultancy Zeta-Tech Associates studied PTC for the railroad administration in 2004 and reported its results “suggest that the railroad industry should carefully consider the opportunity presented by PTC technology, especially in view of its ongoing shortage of line capacity and the need to increase the return on invested capital.” Both systems, it said, provide “significant business benefits to the freight railroads, as well as unquestioned safety benefits through positive enforcement of movement authorities.”

After the 2008 Chatsworth crash, the magazine Design News published a series of articles on PTC titled, “Railroad Safety at What Price?” Then-editor John Dodge recalls being stunned by Burlington’s actions years before.

“There was a proof of concept [for their PTC system] and [Burlington] tried it out, and it worked. It was a $350 million rollout. You can talk to all of the people in the railroad industry, and they will rationalize it, but for more than 20 years there has been a viable safety system that BNSF has been sitting on.”

“Those people who lost their lives in L.A. didn’t have to lose their lives,” Dodge said. “That was my view. Railroads are extremely risk-averse and very regimented. Everything is about moving freight at a lower cost, and that is how it has been for more than 150 years.”

And yet, Metrolink still has no automated system of any sort on its trains, leaving primary responsibility for the safety of hundreds of passengers each trip to the engineer. In the Chatsworth case, engineer Sanchez, was known by supervisors to text or call friends while running the train alone but no action was taken to stop the prohibited behavior.

Feinstein told the California Senate Hearing on Rail Safety, “Not a single mile of California track has modern collision avoidance Positive Train Control systems — though these systems are in place on more than 3,100 miles of American track. … In the past 10 years, the National Transportation Safety Board has investigated 52 rail accidents where the installation of a positive train control system would likely have prevented the accident.”

When Will Passengers Be Safer?

PTC has been on the National Transportation Safety Board’s “Most Wanted List for Transportation Safety Improvements” since 1990. The NTSB has emphasized that such systems are especially needed where passenger trains and freight trains share a single track.

And the concept isn’t totally foreign to U.S. tracks: Amtrak has a system fully implemented in the Northeast Corridor between Washington and Boston, while Alaska and New Jersey are actively developing their own versions.

In the case of the Metrolink, small safety improvements have been initiated, according to the president of the Metrolink Transportation Board, Keith Millhouse. However, most of the new safety measures have yet to be fully implemented. They include: placing a “Second Set of Eyes,” or a second trained engineer in the cab, although only a small percentage of the trains actually have this in action; inward-facing video cameras, which are facing serious resistance from the railroad workers’ unions; ordering new passenger cars and cabs that would decrease injuries during a crash, the delivery of which has been delayed; and changing the operating company from Connex to Amtrak, which will not happen until the end of the current contract next year.

Today, Metrolink officials were to announce that video cameras have been installed on all locomotives in the Metrolink system at a cost of $1 million. That included two inward-facing video cameras, the presence of which is intended to prevent engineers from using cell phones, texting or having unauthorized personnel inside the cab while operating the train.

However, these cameras are not being monitored in real time, but the video will be downloaded each day for random review. Therefore, the cameras cannot directly prevent a crash similar to the 2008, train wreck. Only the possibility of an engineer fearing that he will be identified after the fact for breaking Metrolink rules will translate to possible accident prevention.

One more system that is about to be activated is called “automatic train stop.”

“When the train passes a device, a signal is sounded in the cab that requires the operator to acknowledge the signal that is generated,” Millhouse explained. “If the operator fails to acknowledge the signal then the train will be slowed down. We’re just at the point where we’re ready to turn on the system.”

But automatic train stop is not a new system. “It is somewhat outdated technology,” Millhouse said, and it has limitations.

Between money, technology and geography, Millhouse said Metrolink can’t install and implement PTC by itself.

“We have the largest and most densely congested operating system in the country. Within the Metrolink operating system we have Metrolink, Amtrak, Union Pacific, Burlington Northern Santa Fe and the Coaster system in San Diego, so any equipment that is west of Chicago has the potential to enter this area. We have been proceeding at Metrolink to equip all of our locomotives and trains by 2012.”

Union Pacific has declared that it will implement PTC by 2012, three years before the federal mandate.

Additionally, the major railroads, Union Pacific, Suffolk Northern and Burlington Northern Santa Fe, reported they have reached an agreement on establishing interoperability standards for PTC.

Despite that agreement, on Aug. 25, Burlington Chief Executive Officer Matt Rose told Bloomberg News that it would be extremely difficult for his company to meet the 2015 deadline. Calling the Railroad Safety Act of 2008 “heavy-handed,” he said, “This is just one of those examples of regulation gone awry where there will be unintended consequences.”

He asked that lawmakers allow the carriers to implement PTC only on its busiest lines.

“Implementing PTC on the specified routes by 2015 will be a logistical, technical and financial challenge,” a Burlington spokesperson told Miller-McCune. “The Rail Safety Transportation Act of 2008 is an unfunded mandate. However, BNSF has always said it will make all reasonable efforts to comply with the law.”

Rose said PTC will cost the railroads $10 billion and that Burlington would prefer to install the new technology on its own timetable. In its 2004 report, Zeta-Tech wrote, “PTC is a large investment by any measure. A cost of $1.3 billion to $4.4 billion might seem daunting to an industry with gross revenues of only $35 billion. However, the projected annual savings of $2 billion to $3.6 billion provides a rapid payback period.”

Epilogue

On Sept. 10, Metrolink ran a test to see how much safety improvement has been made on its tracks in the year since the Chatsworth tragedy. Operators intentionally turned what would normally be a green light during rush hour to a red light. The train blew right through it and the engineer, who is required to call out the signals to the conductor, apparently called out the red light as being a green light.

So whether the railroads will actually move forward in the future with an effective and technologically advanced PTC system or whether human error will continue to have the final word on passenger safety, will be determined only by the legal deadline of 2015.

Sign up for our free e-newsletter.

Are you on Facebook? Become our fan.

Follow us on Twitter.