By many accounts, social mobility in America has been on the decline for several decades. Families are increasingly marooned in their income class. Or worse, some adults actually seem to be falling out of the tax brackets in which they were raised (which is decidedly not the kind of mobility most of us have in mind).

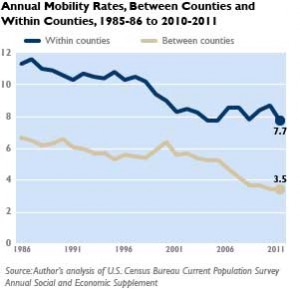

New Census data suggest we’re losing mobility of a different kind: around and across the country, not just up and down its income scales. Americans are literally less mobile than they’ve been at any time since World War II. And this is a troubling trend, too. Some of the decline — which predates the recession — speaks to an aging population that isn’t all that interested in going anywhere. But much of it tracks the immobility of Americans — particularly 20- to 24-year-olds, who would presumably love to leave their parents’ basements if they could.

Miller-McCune’s Washington correspondent Emily Badger follows the ideas informing, explaining and influencing government, from the local think tank circuit to academic research that shapes D.C. policy from afar.

“Those are the years when people move,” said William Frey, a demographer at the Brookings Institution. “They break out of their parents’ homes, they break out of college, they’re starting their careers, they want to be off on their own. The fact that it’s had such a big decline, even in the last five years, means these young people are really putting off their careers, their family lives, their independence.”

Americans in this age group typically move more than anyone else. But that’s no longer the case. Those 25 to 29 years old have supplanted them.

Across the entire country, only 11.6 percent of residents moved last year — and Frey suggests, glumly, that some of these people relocated to move in with each other. By contrast, in the early 1950s, a staggering 20 percent of Americans up and moved each year.

“We knew it had gone down again,” Frey said of the latest numbers. “The question every year is how low can it go? At some point it’s going to pick up.”

The latest data show that people aren’t moving across the country. But they’re not moving across town, either. Intra-county migration is also at an all-time low, following a steady decline that has tracked the aging of the population and the historic rise in homeownership rates.

Frey suggests that the decline in long-distance moves has had as much to do with the collapse of the housing bubble as the recession that followed. Typically, Americans move long distances for jobs.

“People were uncharacteristically making long-distance moves for housing reasons rather than employment reasons,” Frey said, “simply because they were able to get much more affordable homes in some parts of the country.”

This thinking was an anomaly of the housing boom. It sent droves of people to places like Las Vegas. But now a host of factors — the waning allure of cheap real estate, the lack of jobs worth moving to and the simple fact that people can’t get rid of the homes they have — is holding households in place.

“There will be this kind of pent-up demand for a generation of people who will want to be able to get out and spread their wings, start their lives,” Frey predicted (although he’s at a loss to say when we can expect this to happen).

For now, all of this means that the communities that had long been population losers may be buying a little more time — and time that they could spend trying to change peoples’ minds.

“In the interim, some of these places that have been more stagnant. This allows them an opportunity for these stayers to give a second look to staying there,” Frey said. “Maybe they can find it isn’t so bad living in Cleveland or Toledo.”

Sign up for the free Miller-McCune.com e-newsletter.

“Like” Miller-McCune on Facebook.

Follow Miller-McCune on Twitter.

Add Miller-McCune.com news to your site.