Back in 2009, Kevin Evans was one of millions of Americans blindsided by the recession. His 25-year career selling office furniture collapsed. He shed the nice home he could no longer afford, but not a $7,000 credit card debt.

After years of spotty employment, Evans, 58, thought he’d finally recovered last year when he found a better-paying, full-time customer service job in Springfield, Missouri. But early this year, he opened his paycheck and found a quarter of it missing. His credit card lender, Capital One, had garnished his wages. Twice a month, whether he could afford it or not, 25 percent of his pay—the legal limit—would go to his debt, which had ballooned with interest and fees to over $15,000.

“It was a roundhouse from the right that just knocks you down and out,” Evans said.

The recession and its aftermath have fueled an explosion of cases like Evans’. Creditors and collectors have pursued struggling cardholders and other debtors in court, securing judgments that allow them to seize a chunk of even meager earnings. The financial blow can be devastating—more than half of U.S. states allow creditors to take a quarter of after-tax wages. But despite the rise in garnishments, the number of Americans affected has remained unknown.

Nearly five percent of those earning between $25,000 and $40,000 per year had a portion of their wages diverted to pay down consumer debts in 2013.

At the request of ProPublica, ADP, the nation’s largest payroll services provider, undertook a study of 2013 payroll records for 13 million employees. ADP’s report shows that more than one in 10 employees in the prime working ages of 35 to 44 had their wages garnished in 2013.

Roughly half of these debtors, unsurprisingly, owed child support. But a sizable number had their earnings docked for consumer debts, such as credit cards, medical bills, and student loans.

Extended to the entire population of U.S. employees, ADP’s findings indicate that four million workers—about three percent of all employees—had wages taken for a consumer debt in 2013.

Carolyn Carter of the National Consumer Law Center called the level of wage garnishment identified by ADP “alarming.” “States and the federal government should look on reforming our wage garnishment laws with some urgency,” she said.

The increase in consumer debt seizures is “a big change,” largely invisible to researchers because of the lack of data, said Michael Collins, faculty director of the Center for Financial Security at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. The potential financial hardship imposed by these seizures and their sheer number should grab the attention of policymakers, he said. “It is something we should care about.”

ADP’s study, the first large-scale look at how many employees are having their wages garnished and why, reveals what has been a hidden burden for working-class families. Wage seizures were most common among middle-aged, blue-collar workers and lower-income employees. Nearly five percent of those earning between $25,000 and $40,000 per year had a portion of their wages diverted to pay down consumer debts in 2013, ADP found.

Perhaps due to the struggling economy in the region, the rate was highest in the Midwest. There, over six percent of employees earning between $25,000 and $40,000—one in 16—had wages seized over consumer debt. Employees in the Northeast had the lowest rate. The statistics were not broken down by race.

Currently, debtors’ fates depend significantly on where they happen to live. State laws vary widely. Four states—Texas, Pennsylvania, North Carolina, and South Carolina—largely prohibit wage garnishment stemming from consumer debt. Most states, however, allow creditors to seize a quarter of a debtor’s wages—the highest rate permitted under federal law.

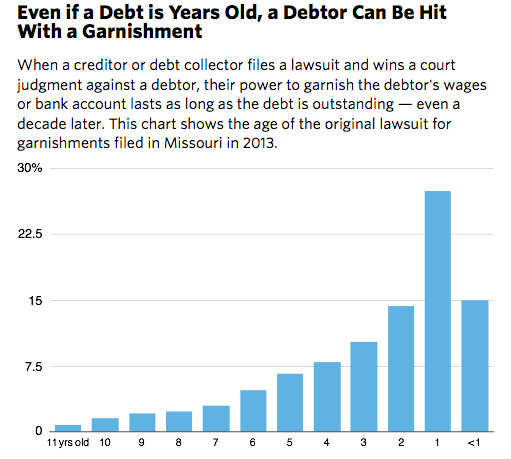

(Source: ProPublica analyzed Missouri state court data for 24 of the state’s 45 circuit courts.)

Evans had the misfortune to live in Missouri, which not only allows creditors to seize 25 percent, but also allows them to continue to charge a high interest rate even after a judgment.

By early 2010, Evans had fallen so far behind that Capital One suspended his card. For months, he made monthly $200 payments toward his $7,000 debt, according to statements reviewed by ProPublica and NPR. But by this time, the payments barely kept pace with the interest piling on at 26 percent. In 2011, when Evans could no longer keep up, Capital One filed suit. Evans was served a summons, but said he didn’t understand that meant there’d be a hearing on his case.

If Evans had lived in neighboring Illinois, the interest rate on his debt would have dropped to under 10 percent after his creditor had won a judgment in court. But in Missouri, creditors can continue to add the contractual rate of interest for the life of the debt, so Evans’ bill kept mounting. Missouri law also allowed Capital One to tack on a $1,200 attorney fee. Some other states cap such fees to no more than a few hundred dollars.

Evans has involuntarily paid over $6,000 this year on his old debt, an average of about $480 each paycheck, but he still owes more than $10,000. “It’s my debt. I want to pay it,” Evans said. But “I need to come up with large quantities of money so I don’t just keep getting pummeled.”

Companies can also seize funds from a borrower’s bank account. There is no data on how frequently this happens, even though it is a common recourse for collectors.

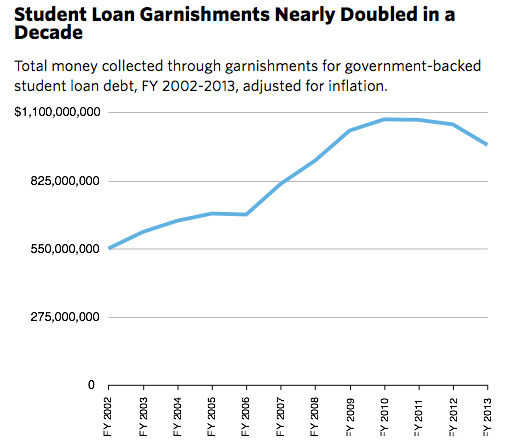

Department of Education data shows that approximately $1 billion has been collected each year over the past several years through these garnishments. The amount is up by about 40 percent since 2006, even after the figures are adjusted for inflation.

The garnishment process for most debts begins in local courts. A company can file suit as soon as a few months after a debtor falls behind. A ProPublica review of court records in eight states shows the bulk of lawsuits are filed by just a few types of creditors and companies. Besides major lenders like Capital One, medical debt is a major source of such suits. High-cost lenders who deal in payday and installment loans also file suits by the thousands. And finally, an outsized portion comes from debt buyers—companies that purchase mostly unpaid credit card bills.

When these creditors and collectors go to court, they are almost always represented by an attorney. Defendants—usually in tough financial straits or unfamiliar with the court system—almost never are. In Clay County, Missouri, where Capital One brought its suit against Evans in 2011, only seven percent of defendants in debt collection cases have their own attorneys, according to ProPublica’s review of state court data. Often the debtors don’t show up to court at all: The most common outcome of a debt collection lawsuit in Missouri (and any other state) is a judgment by default.

In a Clay County courtroom recently, the court was filled with creditors, but debtors were in short supply. Attorneys for hospitals, debt buyers, and lenders milled about, approaching the podium when their cases were called. Often they simply asked for default judgments when debtors failed to show.

Christopher McGraugh, an associate circuit court judge in St. Louis, said the system is designed to give debtors a chance to dispute allegations in suits against them. But in debt collection cases, “it just doesn’t happen that much.”

Some debtors, he said, may believe that they had no reason to attend since they owe the debt. For others, unable to afford an attorney, handling the case on their own is “beyond their sophistication,” he said. As a result, the facts of most cases are never questioned, leaving the plaintiff with a judgment and the ability to pursue a garnishment.

McGraugh, who has presided over thousands of debt collection cases, said when defendants do obtain lawyers, particularly in cases involving debt buyers, they can point to possible holes in the suit. Those cases, he said “are rarely pursued.”

Millions of debt collection lawsuits are filed every year in local courts. In 2011, for instance, the year Capital One went to court against Evans, more than 100,000 such suits were filed in Missouri alone.

Despite these numbers, creditors and debt collectors say they only pursue lawsuits and garnishments against consumers after other collection attempts fail. “Litigation is a very high-cost mechanism for trying to collect a debt,” said Rob Foehl, general counsel at the Association of Credit and Collection Professionals. “It’s really only a small percentage of outstanding debts that go through the process.”

“Legal action is a last resort,” said Capital One spokeswoman Pam Girardo, and the bank only filed suit after Evans “didn’t complete the payment plan we agreed to.”

Experts in garnishment say they’ve seen a clear shift in the type of debts that are pursued. A decade ago, child support accounted for the overwhelming majority of pay seizures, said Amy Bryant, a consultant who advises employers on payroll issues and has written a book on garnishment laws. “The emphasis is now on creditor garnishments,” she said. Today, only about half the seizures are for child support, she said.

(Source: U.S. Department of Education)

To illustrate the rise overall, Bryant provided ProPublica and NPR payroll statistics from a major retailer with approximately 250,000 employees nationwide. The company allowed the data to be used on the condition its name was not used. Since 2007, the number of employees who had their pay seized for consumer debt roughly doubled. As of June of this year, two percent—about 5,000 employees—had ongoing garnishments for consumer debt and just under one percent for student loan debt.

ADP’s analysis also found that the rate of garnishment for child support was most common (3.4 percent), but closely followed by consumer debt, including student loans. The next most common reasons for garnishments were tax levies and payments for bankruptcy plans. (Disclosure: ProPublica retains ADP to provide it with professional employer organization services.)

Wage seizures for student loan debts are governed by different laws than other consumer debts. Collectors can obtain a garnishment after an administrative procedure set by federal rules. Borrowers must also be more than nine months behind before a collector can seek one. Finally, such seizures are capped at 15 percent of disposable income.

Department of Education data shows that approximately $1 billion has been collected each year over the past several years through these garnishments. The amount is up by about 40 percent since 2006, even after the figures are adjusted for inflation. ADP’s analysis did not break out student loans from other types of consumer debt.

Bryant said the rise in garnishments has become an unanticipated burden for employers.

“It becomes very complicated,” she said, particularly for national employers who must navigate the differences in state laws. “It’s very easy to make a mistake in the process.” If an employer does not correctly handle a garnishment order, she said, they can become liable for a portion or even the entirety of the debt in some states.

The burden was enough to prompt the American Payroll Association to request in 2011 that the Uniform Law Commission draft a model state law on wage garnishment. Bryant said employers are hoping that the new law, which is still being drafted, will be adopted by a large number of states and reduce complications.

This post originally appeared on ProPublica as “Unseen Toll: Wages of Millions Seized to Pay Past Debts” and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.