California is not fueling around.

Its California Air Resources Board set the world’s first carbon-fuel emission standards on April 23 — a week after the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, for the first time, proposed declaring greenhouse gasses a threat to public health. That’s almost three years after California started acting on the issue, at times in the teeth of opposition from the White House.

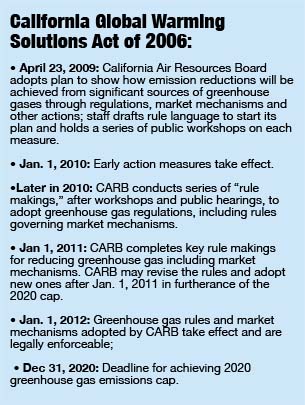

The Golden State’s new standards require fuel providers, refiners, importers and blenders to make sure their products for the state’s market — the largest single-state market in the nation — meet an average declining standard of “carbon intensity.” That will be determined by the sum of greenhouse gas emissions associated with fuel production, transportation and consumption. The California rules will be fully enforced by 2012.

Maureen Gorsen was chief legal counsel for the state team that developed the 2006 law, known as California Global Warming Solutions Act, which led to April’s vote. Now a private attorney with the national law firm of Alston & Bird, Gorsen said that more than 30 years ago, California paved the way for regulating the way automobile engines burned fuel. Now, the state will regulate fuels with a “cradle-to-the-grave” approach, she said.

Princeton Prod

More than three years ago, state officials “decided the debate over climate was over” and California — the world’s 10th largest emitter of carbon dioxide, according to the California League of Conservation Voters — wasn’t going to wait for the federal Environmental Protection Agency to do something about the public threat carbon emissions pose, she said. (The EPA did not comment on the issue for this article.)

California officials were convinced something could be done about harmful gas emissions partly because of research by Princeton University professors Stephen Pacala and Robert Socolow, who first said in 2004 that reduction of global carbon-dioxide emissions by 1 billion tons of carbon per year in 2057 could be achieved. They said this could be done by an “aggressive, globally coordinated scale-up of a mix of already commercialized or nearly commercialized technologies.”

Pacala and Socolow measured the emission cuts in what they called “wedges.” A wedge equals about 1 billion tons of carbon a year. The more than 8 billion tons of carbon in the atmosphere now is expected to double to 14 billion tons per year over the next 50 years as the world population increases and people consume more energy. To keep emissions stable, technologies and conservation efforts would have to prevent 7 billion tons worth of emissions per year by 2054.

The professors, part of Princeton’s Ford and BP-funded Carbon Mitigation Initiative, have delivered a number of lectures around the county where they said “implementing eight wedges should enable the world to achieve the interim goal of emitting no more CO2 (or carbon dioxide) globally in 2057 than today, and in the following 50 years driving CO2 emissions to net-zero emissions would place humanity, approximately, on a path to stabilizing the climate at a concentration less than double the pre-industrial concentration.”

Theoretically, the professors said, if fuels such as ethanol are used with a combination of solar, wind nuclear and other power sources, the goal of slashing greenhouse gases can be met. And of course, reality might prove more difficult than theory, as some observers have commented about their “wedge” plan.

While their concept gained a following in California and beyond, it was still a surprising move in 2006 when Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger — a Republican — signed the California Global Warming Solutions Act, known in Sacramento as Assembly Bill 32. His aides told him if carbon emissions weren’t reduced, the effects of climate change, especially global warming, would damage the state and world’s habitat and economy, which three years ago was much stronger that it is today.

A follow-up executive order from the governor in 2007 called for the Air Resources Board to develop the fuel emissions standards, which were approved in April, said board spokesman Stanley Young. He said the fuel standards follow the state’s campaign to cut vehicle emissions by 30 percent by 2016.

Air Resources Board officials said they plan to do this without further upsetting the state’s sagging economy. They said the new rules can do this by increasing the market for alternative-fuel vehicles and cutting 16 million metric tons of greenhouse gas emissions by 2020, which they claim will generate thousands of jobs along the way.

Ethanol Ethics

Dimitri Stanich, public information officer with the California Air Resources Board, or CARB, said the push is to bring “a multiplicity of alternative fuels to market in the state.

“It won’t happen overnight. We want the market to dictate the economic process in bringing the need to bring more fuels to California.”

While several measures were taken to ensure that ethanol would play a role in reaching the CARB’s proposed low-carbon fuel standard, the measures weren’t universally hailed by producers. And CARB officials admit some ethanol producers have good reasons to be concerned. “That’s because their production process, which involves burning coal, is too carbon intensive,” Stanich said. “We hope they streamline their process to cut their carbon emissions.”

At least 20 ethanol producers plan to open operations in California soon, which would create 3,000 jobs in rural areas, Stanich said. However, he admitted several producers already operating in the state are having what he called “a difficult time” because of the rising cost of corn, currently — and controversially — the primary source of U.S. ethanol.

However, he said use of other non-food crops, such as switch grass, to produce ethanol is growing worldwide and in California specifically. Companies such as Ceres in Thousand Oaks, Calif., are developing types of switch grass that can be used for this purpose. “Switch grass is an invasive weed that can be found all over California,” Stanich said. “It looks very promising.”

“While the low-carbon fuel standard is designed to favor low-carbon, non-food energy crops like switch grass, high-biomass sorghum and miscanthus (crops Ceres produces), we are concerned about the precedents it may set and the uncertainty it may create as the advanced biofuel industry seeks the capital it needs to grow,” said Gary Koppenjan, Ceres corporate communications manager.

“Going forward, policymakers, investors and the industry need to pursue regulations based on demonstrable data and studies, and rely less on computer simulations based on well-intended, but speculative assumptions.”

For the example, the CARB sees an $11 billion reduction in the price of fuel. “Whether (fuel producers) want to pass that along to the consumers is their choice, but we think it is a wise business strategy,” Stanich said.

The $11 billion cost reduction is based on the anticipation that the price of crude oil will become more than $90 per gallon, CARB officials said. When that happens, they said, the cost of producing a gallon of low-carbon fuel will be about $2.60 when it comes from low-carbon fuel plant. The “cost reduction” would result from consumers’ “savings” by buying fuel at that price rather than just using crude oil that would yield a nearly $4-per-gallon product.

Another Alston & Bird attorney, Jocelyn Thompson, has dealt with the CARB for four decades. Thompson said she’s “very skeptical” of the way the state agency deals with cost estimates on its policies. “They often underestimate what it takes to get the job done. I’m very skeptical about their cost equation.”

“This is the first regulation (that) could have a widespread and costly impact on how fuels are made,” she said. “This totally overhauls our fuels and how we use them … whether it’s taking goods to market, driving to work or riding in the bus.”

She said her oil company clients have realized this has been coming for the past two years and have been “trying to find ways to comply with the rules.” She said, “They are trying to figure out how to run their businesses with them.”

As California moves forward on its own and about a dozen other states watch closely, the EPA’s action earlier in April sets the stage for a series of public hearings on climate change soon.

Sign up for our free e-newsletter.

Are you on Facebook? Become our fan.

Follow us on Twitter.