The hundred thousand people of the Kalalé District in northern Benin, a country in West Africa, like billions in the developing world, are not connected to power lines. All but one out of 20 rely on farming for their livelihood, and most just scrape by. During the dry season from November through April, many suffer from malnutrition, a condition so common it gets its own name, kwashiorkor.

One Kalalian, Mamoudou Setamou, teaches about insects and integrated pest management at Texas A&M. He hasn’t forgotten his roots and returns to Kalalé to participate in local community functions including district council meetings. At one such gathering in 2006, the council discussed ways of generating electricity when it became clear that the central government had no intention of bringing electrical lines into the district anytime soon. For his part, Setamou believed that photovoltaics best fit his countrymen’s needs.

Back in America, he stopped at the headquarters of the Solar Electric Light Fund, a Washington, D.C.-based nongovernmental organization that traditionally focuses on using solar to bring electricity to poor, remote or rural areas — like Kalalé.

Robert Freling, SELF’s executive director, answered the phone the day Seamou called. “We have to turn down most requests,” Freling recalled, “but we were intrigued with doing not just a one-off village but an entire district. We’d done the one-offs, but this was a chance to do 44 villages and 100,000 people.”

After talking with the professor, SELF developed a master plan to solarize much of the infrastructure in the 44 villages, bringing the region things like street lighting and wireless Internet, and improving education and health care.

But when a SELF team visited Kalalé, their priorities changed; the overwhelming need in the area was having enough to eat. As SELF staffers would later write, “Despite its great potential, agricultural production in Kalalé remains weak and easily influenced by natural conditions. Rainfall is the sole source of water supply for crop production, which is limited to only a six-month rainy season each year.”

So the focus turned to irrigation. SELF sought the help of Dov Pasternak, an Israeli agronomist based in Niger who had created a low-pressure drip irrigation system that brings to poor farmers in sub-Sahara Africa the advantages of that technology at a fraction of the cost.

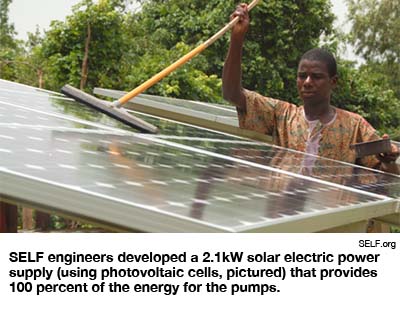

Though Pasternak had overseen the installation of thousands of such systems, his clients had used pumps powered by diesel engines and not photovoltaics. SELF and Pasternak discussed the advantages of photovoltaics for such projects, looking at data from sources as disparate as the U.S. National Renewable Energy Lab to on-the-ground work in dry Namibia. Over 20 years, for example, running a diesel generator would cost nearly four times as much as using the more-expensive photovoltaics.

Reliability was also an issue. Thousands of diesel generators have broken down in this part of the world, never to run again due to scarce parts and few mechanics, while service also grinds to a halt for lack of fuel. A 10-year study of PV water pumping systems in Mexico found that after a decade, 60 percent of the systems were still working — and when they weren’t, the problem usually arose from the pump, not the PV.

Photovoltaics, meanwhile, work best during dry weather in full sun — when crops need water most. In Namibia, where water use focuses more on farm animals and less on crops, South African researchers also noted that the PVs produced no carbon dioxide emissions, didn’t erode the borehole water was pumped from and allowed better rangeland conservation — all advantages over diesel.

“We cannot and will not use diesel generators to pump water,” Freling said. “Dov was skeptical at first, but now he has become a huge convert when it comes to using solar.”

The systems, by Third World standards, weren’t cheap — $18,000 each to install and almost $6,000 a year to maintain. But with help from the Association pour le Developpement Economique Social et Culturel de Kalalé, $100,000 from a World Bank’s Global Development Marketplace grant, and private donors, SELF put in three solar-powered irrigation systems, each serving 2.1 kilowatt system irrigating 1.25 acres.

Since 2007, when the pilot systems went in, results have been amazing. The farmers, all women, have grown almost 2 tons of produce per month per system. That’s enough to feed themselves and their families and to produce a large surplus (80 percent of what they grow) of highly valued vegetables ranging from tomatoes and carrots to amaranth and moringa to sell at local markets. Money derived from sales has allowed them to purchase staples and protein sources to hold them over during the dry season. Previously, they had to ration their supplies until the next harvest. They also increased their intake of vegetables significantly, amounting to 1 pound per day per person, equal to the daily recommended five servings for each individual.

“The photovoltaic irrigation drip system could potentially become a game changer for agricultural development over time,” researcher Jennifer Burney of Stanford University’s Program on Food Security and the Environment told her school’s Ashley Dean. A paper by Burney, program director Rosamond Naylor, Pasternak, Lennart Woltering and Marshall Burke is scheduled to appear in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences strongly supporting the use of PV in combination with drip irrigation.

And as an impressed researcher remarked, most of the change took place during the dry season. Freeing farmers from enslavement to the whims of weather, those studying the SELF projects concluded, “Widespread adoption of photovoltaic drip irrigation systems could be an important source of poverty alleviation and food security in the marginal environments common to sub-Saharan Africa.”

Meanwhile, the project continues for SELF, which is still working on the solarization of the entire district. In February, said Freling, the project is solar-powered pumping of drinking water in Kalalé, since the existing pumps are dedicated to drip irrigation right now.

Sign up for our free e-newsletter.

Are you on Facebook? Become our fan.

Follow us on Twitter.