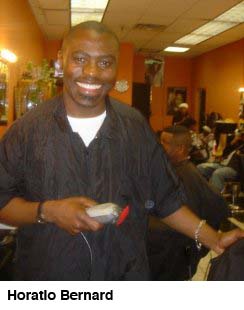

It’s been almost a year since Horatio Bernard effectively lost his Baltimore row house to foreclosure and roughly 15 months since he last made a payment on his primary mortgage.

And yet to his amazement and those following his story, Bernard continues living in the home with his ailing mother without any sign of an eviction notice or word from his lender, in this case JP Morgan Chase and then US Bank.

“I haven’t paid a dime,” Bernard told me, sounding gleeful over the phone.

Earlier this year, Bernard was defiant on staying in his home even though the bank had already tried selling it at auction last November. Bernard, a Liberian immigrant, took a shot at the American dream at a time in 2005 when that dream involved risky subprime loans. On top of that, he’d been victimized by a foreclosure prevention scam by New Hope Modifications, which the New Jersey attorney general since indicted on fraud charges.

“We’re as mystified by it as he is,” said Joe Cox, a community organizer with the Association of Community Organizations for Reform Now in Baltimore. ACORN, under fire for unrelated allegations that two branches may have helped an activist posing as a pimp avoid taxes, actually spends considerable resources dealing with cases like Bernard’s.

Attorneys with ACORN — during what’s called the “redemption period” after an auction but before the bank takes possession of the house — filed two appeals for Bernard in Baltimore County Court. Both were unsuccessful, and a judge ratified the foreclosure in July. In January, Chase transferred the home to US Bank, and since then, it doesn’t appear the bank has taken possession because nowhere is the home listed as bank-owned yet.

“We’ve had plenty of people give up and move, but I can’t recall a sheriff actually coming out,” Cox said.

Bernard’s case is testing the limits. He hasn’t paid a cent toward his primary mortgage since July, but continues making payments on a second home equity loan for $60,000. And still no eviction notice.

There’s even a chance Bernard could get to stay in his home a lot longer. That’s because like hundreds of thousands of other homeowners in America these days, Bernard falls into what real estate experts call a shadow market, the growing backlog of foreclosures and bank-owned properties yet to reach real estate markets.

For various reasons, banks have slowed down the foreclosure process causing a reprieve for homeowners like Bernard while at the same time building a swell of foreclosed homes delayed from hitting the market. If they were to flood real estate markets at once, banks would suffer under a glut of inventory drawing down overall prices. So the banks have held back, in effect drawing out the nation’s recovery.

The shadow market today – those in distress or in some stage of foreclosure — represents roughly 14 percent of existing mortgages, says Rick Sharga, senior vice president of RealtyTrac, which compiles nationwide data on foreclosures.

“Right now what we’re seeing is delays in the entire process,” Sharga said. “It started in the fourth quarter of last year where we saw a spike in delinquencies that didn’t match a corresponding spike in foreclosures. What that suggested to us is it was taking the banks longer, for whatever reason, to execute on the foreclosure process. So we’re getting a buildup of properties that normally would have been in foreclosure but weren’t. That has continued to escalate. We’re now at record levels of delinquencies. Probably 10 percent of active mortgages are delinquent, and another 4 percent are in foreclosure.”

In rough numbers there are now about 400,000 bank-owned homes that should be on the market, but are not. Sharga said another 1.5 million homes are in foreclosure and about 5 million delinquent – anywhere from one month to one year late on payments.

“We know when the banks are taking properties back it’s taking longer for them to put them back on the market,” Sharga said. “Last year our analysis found that only 31 percent of bank-owned properties were listed for sale. We’re assuming, given part of the market dynamics this year, it’s closer to 50 percent.”

That would increase the supply of available homes by 10 to 15 percent, Sharga said.

“The question is how rapidly or slowly the banks will decide to release these properties to the market,” Sharga said. “What we see more likely is an extended period for the housing market to recover. We really probably won’t be back to normal levels of foreclosure activity until 2012 or 2013.”

Tom Kelly, spokesman for JP Morgan Chase, said without specifics he couldn’t comment on Bernard’s story. In general, he said, the $75 billion Home Affordable Modification Program — which pays many of the same banks behind the housing crisis to modify loans — is working.

That’s the message not just from Kelly, but the Obama administration, which reported recently that the program met its initial goal to modify 500,000 home loans in the first six months of the program.

Kelly explained the process for homeowners that can’t make it work. “Once the auction occurs we have local companies that will knock on the door,” Kelly said. “The person will say I’d like to get my act together and be out by the end of the month and we’ll say OK. Or we’ll talk about cash for keys.”

Cash for keys is industry parlance for offering a few thousand dollars for move-out costs.

“If they say we’re not leaving then we’ll go through a whole eviction process,” Kelly said, though he wouldn’t share how many evictions the bank has had to carry out as a result of foreclosures. “If there’s a possibility of doing a modification, if they’ve applied, we’ll basically put things on hold until we work through it and see if there’s a way to keep someone in the house. Between April and the end of August, JP Morgan Chase has modified 224,000 home loans.”

In several states homeowners have a full year, called a redemption period, after their home might be sold at auction to reclaim it. In Bernard’s state of Maryland, the redemption period is just 30 days.

In some instances, homeowners think they’ve lost their home before the lender actually takes possession. A rising number of cases in Ohio illustrate what happens when banks “walk away” from foreclosed homes, figuring they’d lose more money if they take possession.

In Bernard’s case, JP Morgan Chase put the house up for auction at $100,000 less than the $258,000 Bernard paid for the home in 2005. In January, Chase transferred the house to US Bank. Monthly payments on a 30-year fixed rate mortgage would be around $700. Bernard is willing and able to pay much more. But for now, he’s just waiting to be evicted.

“What it really shows me is how ridiculous this system is,” said ACORN’s Cox. “You’ve got a guy who wants to pay much more than the property is up for sale for. What it looks to me like is that the bank is making a calculated risk and saying they’d rather have someone living there for free than have a vacant house.”

Kelly at JP Morgan Chase denies this or that the bank has chosen to walk away from the home.

“Banks sometimes walk away but this case doesn’t sound like the normal process,” Kelly said. “The people who have legitimate hardships, we work with them as well as we can to keep them in the house. If they are not even trying to pay, then they need to leave.”

Sign up for our free e-newsletter.

Are you on Facebook? Become our fan.

Follow us on Twitter.