How much money do your parents make? For young workers, particularly those in the digital creative sector that’s occupying our culture’s imagination at the moment, the question is the ultimate taboo. How did you fund the unpaid internships that got you that media job? What kind of background lets you live in one of the most expensive cities on Earth with an entry-level salary and make it look easy?

A new report by NPR’s Planet Money pulls back the curtain on what we might call the Hannah Horvath syndrome, after Lena Dunham’s Girls character whose life in New York City is disrupted when her parents cut her off. In contrast with blue-collar jobs, workers in creative fields come from families with high annual incomes during their childhoods. Designers, musicians, and artists averaged a family income of $65,000 to $70,000 while growing up, while doctors came in lower at $55,000 to $60,000. Construction workers and truck drivers are in the $40,000 to $45,000 range, and on the very bottom are service industry workers and farmers at $40,000 and below.

The so-called one percent is actually less monolithic than the buzzword suggests. In fact, it’s really the top 0.1 percent whose wealth is ballooning out of proportion with the rest of the economy.

NPR’s data was drawn from the NLSY79, a group of 12,686 young men and women who have been surveyed every two years since 1979 (when the subjects were between 14 and 22 years old) to get a picture of the U.S.’s socio-economic stratification. While Planet Money warns that the information isn’t necessarily a perfect representation of the entire country, it does give us an insight into the nature of U.S. inequality—namely, that it’s structural and self-perpetuating.

Doctors, executives, and computer programmers were all likely to both come from high-income families and outstrip their parents in income. On the other end, however, service industry, construction, and farming jobs either increased only slightly on their family’s income or fell beneath it. Hannah Horvath might want to watch out—artists are also likely to earn less than their parents.

Families with lower income have less access to the resources they need to provide more opportunities to their offspring, whether that’s a strong home environment, early childhood education, or a shot at going to an expensive university without crippling debt. (Just 48 percent of poor children are ready to start school at the age of five, a Brookings study found, compared to 75 percent of kids from moderate to high-income families.) Parents with higher incomes often have a surplus of the money and time needed to launch their children into higher-paying careers, as Planet Money’s infographics show.

But this cyclical trap isn’t just happening at the low end of the spectrum. Even the “one percent” at the highest levels of the economy are stuck in it.

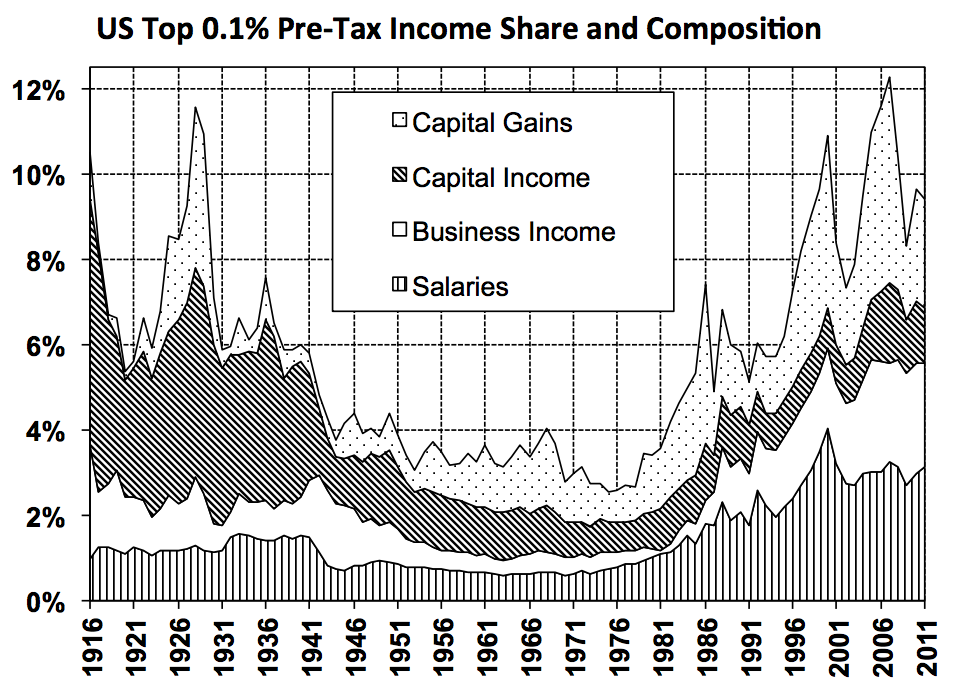

A SURPRISING NEW STUDY by economists Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman found that the so-called one percent is actually less monolithic than the buzzword suggests. In fact, it’s really the top 0.1 percent whose wealth is ballooning out of proportion with the rest of the economy. The proportion of wealth controlled by that very top slice has doubled since its century low in 1978 to over 20 percent, and in the past decade it is increasing at an even higher rate. Outside of the top 0.1 percent, there’s actually little wealth gain in the other 0.9 of the one percent.

Saez and Zucman explain that in the early part of the 20th century, there was tremendous income inequality—it was the Downton Abbey era of masters and servants, land-owners and tenant farmers. When war and the Great Depression hit, the top earners were hurt most, and high government taxes on income and inheritance (which raised money for military efforts and the New Deal) prevented family wealth from being perpetuated as much as it would have been.

The recent surge in the earnings of the 0.1 percent has been matched with a falling tax rate on income, a correlation that the economists say is “strong but not perfect.” Yet the mounting inequality isn’t just about the lack of a high-income tax on the rich. It’s about the different kinds of income the wealthiest part of the economy receives.

Over the past decade, the 0.1 percent has benefitted from the largest bump in income not from getting paid higher salaries but in earning more from capital gains, capital income, and business income. This includes more abstract forms of wealth like rents received from real estate holdings, stock dividends, and pay-offs from owning equity in companies rather than direct labor. Salary income for the 0.1 percent has leveled off since 2000 and has stayed relatively even with the growth of salary income for the rest of the economy. It’s this separation between capital income and salary income that is driving extreme inequality.

THE FAMILIES AND CHILDREN studied by Planet Money have little access to the same generators of capital income that the one percent own. It’s hard enough for lower-earning families to pay for their children’s education, let alone invest in real estate or business. In his much buzzed-about new book Capital in the Twenty-First Century, French economist Thomas Piketty makes a distinction between wealth—forms of capital that produce passive value—and income—the money gained from salary wages (Piketty worked with Saez and Zucman on research for the book).

Poorer families subsist on wages, true of the lower end of workers in the Planet Money research, which have been growing more slowly than other forms of capital. Piketty argues that this is the main driver of inequality: When the economy (the marketplace that produces wages) is growing, it’s easier to make gains with capital than it is in wage income from labor, and inequality increases. The period in the middle of the 20th century, with its political and economic tumult when capital was less productive than labor, may have been an anomaly.

If we don’t do something about the disparity, Piketty predicts “levels of inequality never before seen.” He suggests higher taxes on the wealthiest earners, a recommendation that Saez and Zucman echo. “High top tax rates reduce the pre-tax income gap without visible effect on economic growth,” they conclude. Such policies wouldn’t just work to reduce inequality, they would result in more opportunities and more diverse forms of wealth for more people, and that’s undoubtedly a good thing.