On Wednesday, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act passed the House or Representatives (for the second time); it’s now headed to President Donald Trump for his signature. In the House, the legislation passed on a 227-203 vote. Twelve Republicans—all but one of them from the high tax states of New York, New Jersey, or California—voted against the legislation; no Democrats voted for it. In the Senate, the legislation passed on a 51-48 party line vote (Senator John McCain was absent).

The final version of the legislation makes a number of changes to both the corporate and individual side of the tax code. On the business side, the legislation permanently reduces the corporate tax rate to 21 percent, changes the way that income from pass-through businesses is taxed, transitions the country to a territorial tax system, and eliminates the corporate alternative minimum tax.

On the individual side, the legislation maintains seven tax brackets but (temporarily) cuts marginal tax rates for earners across the income spectrum (including the wealthiest Americans). The bill also doubles the standard deduction, eliminates personal exemptions, expands the child tax credit (although not in a manner that delivers big benefits to the poorest families), caps the state and local tax deduction (at $10,000), lowers the cap on the mortgage interest deduction, increases the threshold at which the alternative minimum tax and estate taxes apply, and eliminates the penalty associated with the Affordable Care Act’s individual mandate. Unlike the reduction in the corporate rate, most of the changes to the individual side of the tax code essentially expire after 2025. (One notable exception to this is the use of a slower rate of inflation, which means taxpayers will be pushed into higher tax brackets sooner than under current law.)

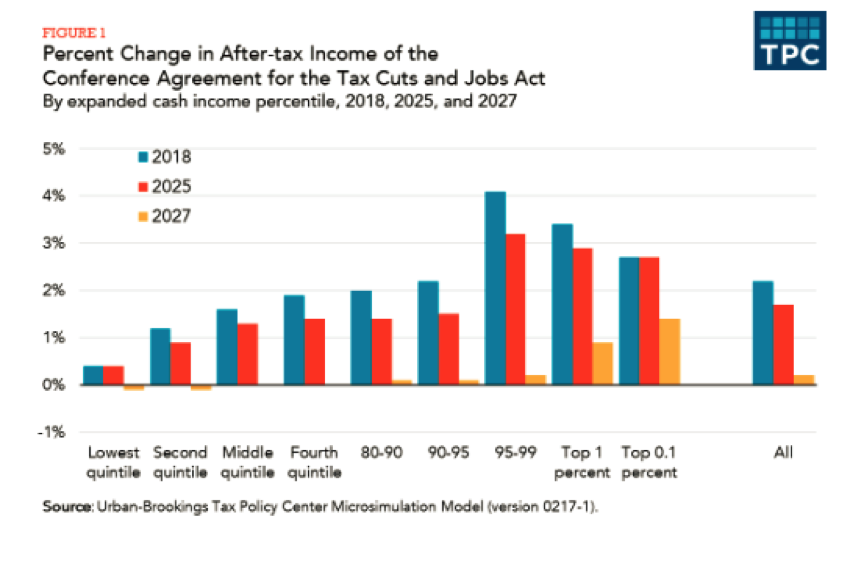

In an analysis released on Monday, the non-partisan Tax Policy Center took a look at how the final version of the legislation will affect taxpayers across the income distribution. In 2018, all income groups would, on average, see an increase in their after-tax income, and only 5 percent of taxpayers in 2018 would see their taxes go up. (This is quite a bit lower than the percentage of taxpayers who would have seen higher taxes under the versions of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act that passed the House and Senate earlier this year.)

By 2027, however, many Americans—53 percent of them—would indeed see higher taxes as a result of the legislation (assuming the changes to the individual side of the tax code are not renewed). As with previous versions of the legislation, the bulk of the bill’s benefits will flow to the highest earners, a trend that is particularly pronounced in later years. The chart below, from the Tax Policy Center report, illustrates how the income effects change over time:

Republicans maintain that the legislation will jump-start the economy and produce a “trickle-down” effect that will benefit middle-income Americans. Analyses of the growth effects of the final version of the bill predict it will modestly increase the United States’ gross domestic product (GDP)—different models predict GDP will be anywhere from 0.6 percent to 1.7 percent higher by 2027, due to the law—and substantially increase the federal deficit (by between $448 billion to $2.2 trillion) over the next decade.

The Joint Committee on Taxation, the official congressional scorekeeper on tax policy, has yet to release its estimates of how the final version of the legislation will affect economic growth, but projects it will increase the federal deficit by a bit less than $1.5 trillion, on a static basis, over the next 10 years.