One of the many reasons that the phrase “President Donald Trump” exists is that he campaigned to change the fact that America is “the highest taxed country in the world.”

On the campaign trail, Trump promised lowering corporate taxes, which he said would promote economic development—instead of paying money to the government, he reasoned, corporations would invest it back into production or wages. Never mind that a 2016 study by Brookings found that “the net impact on growth [after lowering taxes] is uncertain, but many estimates suggest it is either small or negative”—the gripe that American taxes are too high is a perennially popular one among constituents.

But is the United States actually the highest taxed country in the world for businesses? This is where things get nice and murky.

Currently, the official statutory corporate tax rate in the U.S.—that is, the legally imposed percentage of income that corporations are instructed to pay the government—is 35 percent. That’s the highest official rate in the world, and Trump wants to cut it to 15 percent. However, as a new report by the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy shows, that 35 percent is not at all the actual tax rate the government is collecting from major corporations.

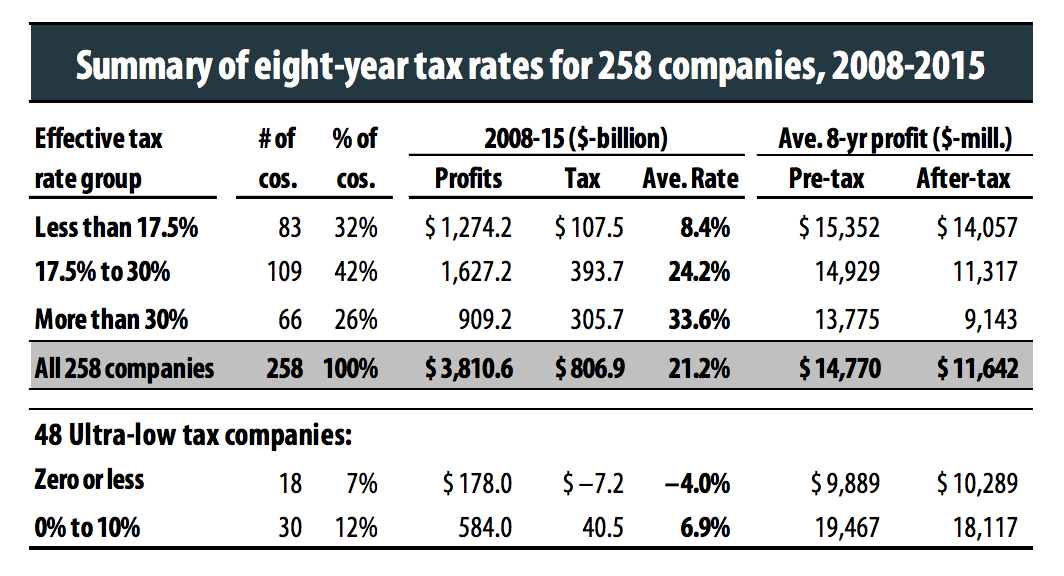

The study examined 258 companies that, between 2008 and 2015, were on the Fortune 500 list and were continually profitable. They found that, rather than the 35 percent rate owed, these companies paid an average of only 21.2 percent, a rate that is below-average compared to the statutory corporate tax rates of other developed countries in the world. (In comparison, France has a tax rate of 33.33 percent and Portugal has 21 percent.)

Why the near 14-point discrepancy? The study finds that major companies aren’t doing anything overtly illegal: Instead, they are taking advantage of the many different ways embedded in the U.S. tax system that allow corporations to keep money from being collected. “Tax avoidance”—when one party arranges their financial affairs to pay the least possible taxes within the law—is precisely that: lawful.

“We put a lot of the blame on Congress,” says Richard Phillips, a senior policy analyst for ITEP and one of the authors of the study. “We think Congress can end all this tax avoidance tomorrow if they wanted, they just need to close loopholes and tax breaks.”

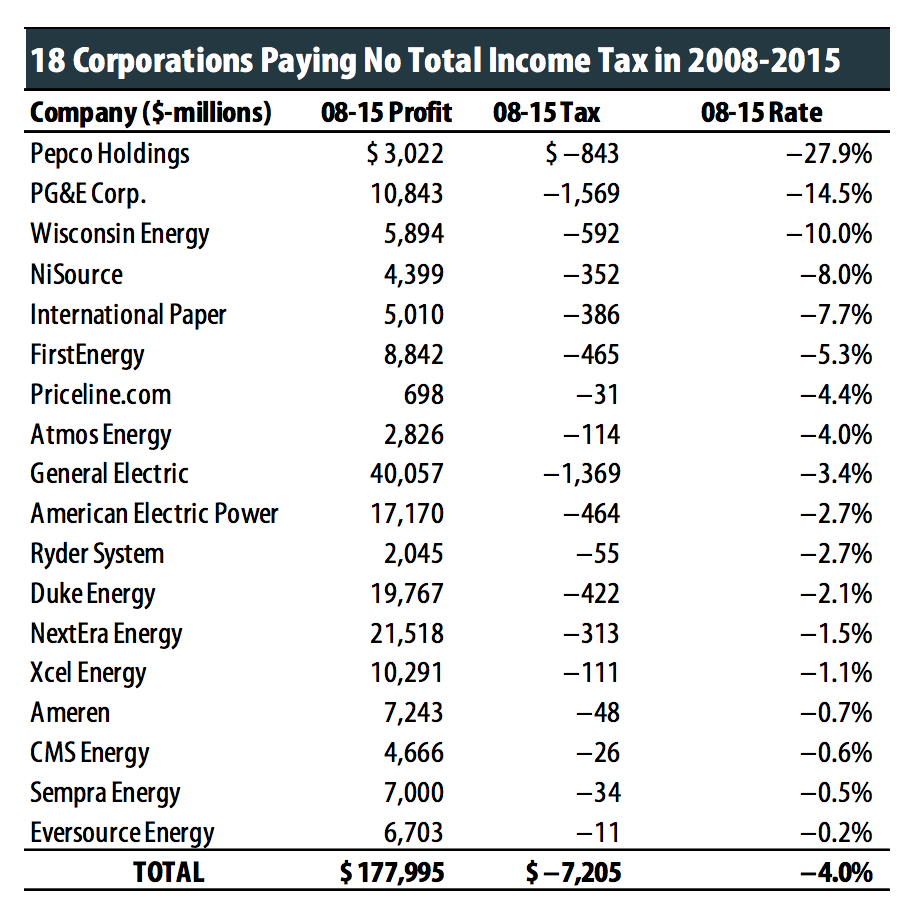

Thirty of the 258 companies paid between zero and 10 percent during the eight years studied, while 18 others paid less than zero percent. The study highlights that it’s not all of corporate America avoiding 25 percent or more in taxes: Retail and health-care companies, for instance, were more likely to pay close to the 35 percent rate, as they are physically beholden to the border constraints that befall purely domestic companies. Multinational corporations, on the other hand, can try to keep as much revenue as they can—as businesses do—by creating accounts in “tax havens” like Ireland or the Cayman Islands.

This is called offshoring, and it allowed the top 50 U.S. companies to keep $1.4 trillion away from taxes in 2014, according to a 2016 study by Oxfam. (Apple held the most money offshore, at $181 billion.) These companies tend to pay more taxes, percentage-wise, to foreign governments than to the U.S.; of the 107 companies that collected more than 10 percent of their worldwide income abroad, 62 paid higher foreign tax rates on that income than the rate they paid to the U.S. on their domestic income.

While offshoring is the loophole most often exploited by major corporations, according to Phillips, there are other ways for profitable companies to drastically cut the U.S.’s 35 percent rate on their own. Corporations can do everything from filing executive stock options as “costs” to lower their tax burden to utilizing “accelerated depreciation,” where companies can deduct the cost of assets at a faster rate than their value actually decreases (a common tactic used by utilities corporations). Or, they may simply have the luck (or lobbyist power) to get Congress to issue an industry-specific subsidy or tax break.

“Big corporations simply have a lot of resources that they can devote to tax minimization,” James Spindler, a professor at the University of Texas School of Law, writes in an email. “Most corporations play by the rules, but they are better at it than we are.”

Because none of these tactics are illegal, experts say the only real solution is changing the rules of how the corporate taxing procedure works. But the likelihood of accomplishing this—a daunting task under the Obama administration, now ideologically opposed to the current team in the White House—seems low. “[Fixing these loopholes] is the hard part of corporate tax reform, and this Congress seems far more intent on doing the easy part, which is cutting the statutory rate,” Richard Pomp, a law professor at the University of Connecticut Law School, writes. “The report offers a broad road-map to reform, and it’s a map our elected officials aren’t consulting.”

That doesn’t mean lawmakers and policymakers haven’t offered solutions: Fixing the loophole of accelerated depreciation could mean simply changing to a straight-line depreciation model, according to the non-profit Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget. Senator Eric Brakey (R-Maine) has proposed eliminating tax credits to reduce tax breaks for specific industries. The offshore tax haven problem is a little trickier, but may involve taxing at the point of consumption, not production.

But how likely are any of these solutions to be implemented? To pay attention to the current rhetoric coming out of the White House the answer is a solid “not realistic.” Now’s probably a good time to remind everyone that the county’s highest-elected official, in a nationally televised presidential debate, claimed that not paying his taxes made him smart.