Recently, many right-wingers and racists swore off Nike products upon the company’s release of an ad featuring quarterback-turned-activist Colin Kaepernick. Meanwhile, on the other side of the political spectrum, another boycott was brewing—until it wasn’t.

In the waning hours before the start of Labor Day weekend, Eric Bauman, the chair of the California Democratic Party, fired out a passionate call to boycott In-N-Out Burger. His sanction was apparently prompted by a Los Angeles magazine article reporting the iconic California chain’s recent donation of $25,000 to the Republican Party:

Et tu In-N-Out? Tens of thousands of dollars donated to the California Republican Party… it’s time to #BoycottInNOut – let Trump and his cronies support these creeps… perhaps animal style!https://t.co/9zkdFaG5CJ

— EricBauman – The UnCommon Sense Democrat (@EricBauman) August 30, 2018

Inspired by the brashness of a state political leader mounting a guns-blazing attack on such an unimpeachable institution of California culture, many on social media immediately fell into their respective battle positions: Left-leaning posters voiced their support for the boycott, and the right-wing media ecosystem began a pushback in favor of In-N-Out. Infowars articles appeared, and Rand Paul tweeted a picture of himself holding a Double-Double. (The nearest In-N-Out to Paul’s home state of Kentucky is roughly 1,000 miles away.) Other observers pointed out that In-N-Out had also recently donated to a Californians for Jobs and a Strong Economy, a PAC that funds the campaigns of pro-business Democrats. By the morning, a full-blown social media headache had emerged for Bauman and California Dems.

Bauman quickly walked back the tweet, emphasizing to reporters that the California Democratic Party was absolutely not boycotting In-N-Out. In fact, Bauman himself wasn’t even boycotting the fast food giant. “Are you kidding me?” Bauman told the Fresno Bee, when asked if he had really forsworn the restaurant. “I’m gonna buy my staff In-N-Out burgers to celebrate our victory.”

Despite Bauman’s clarification about the boycott’s non-existence, the headfake at In-N-Out did drive a noticeable increase in small-dollar donations to the California Democratic Party in the days following Bauman’s tweet.

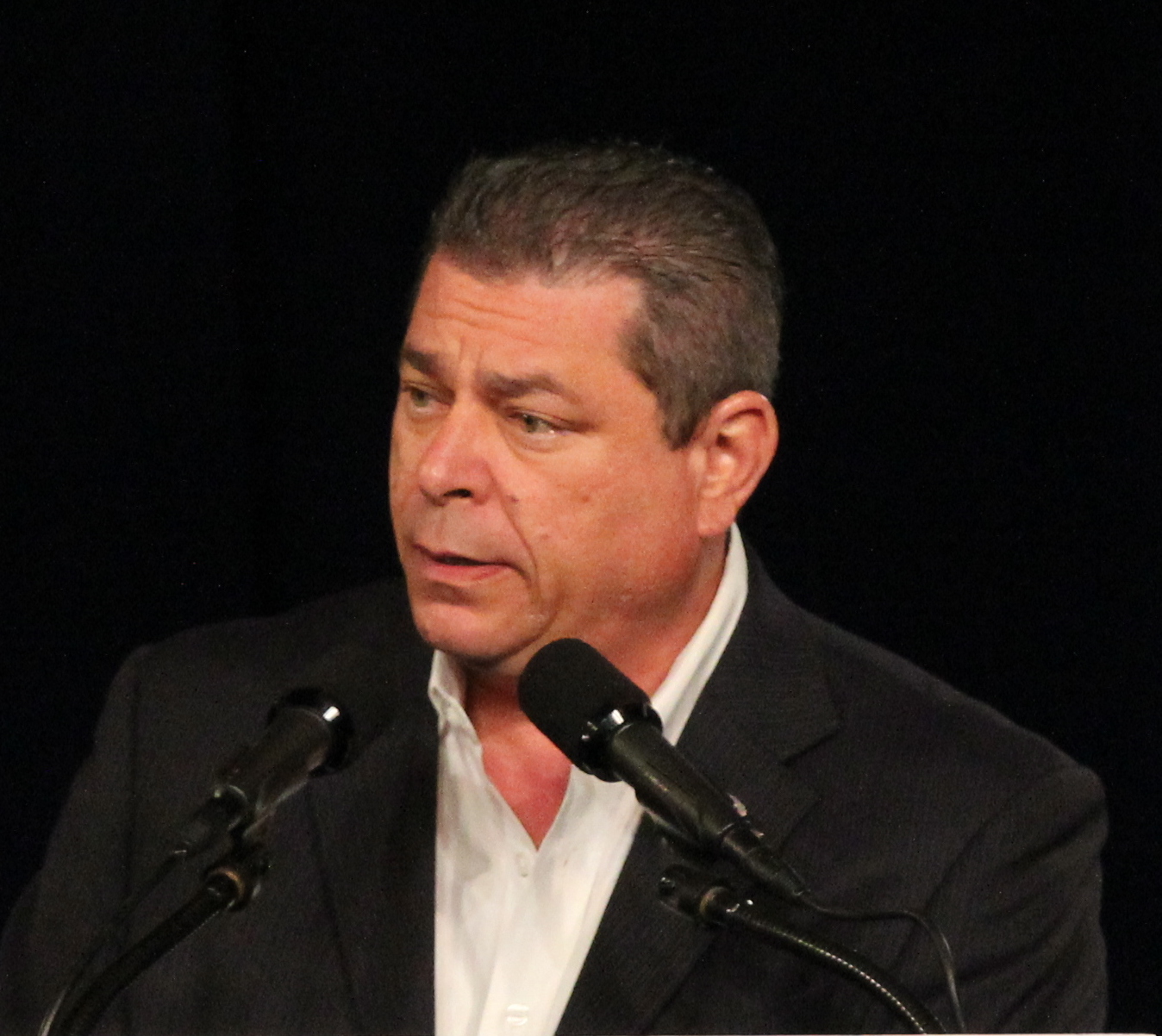

To discuss the non-boycott, social media headaches, and the intensified politicization of every facet of life in the United States, Pacific Standard spoke to the communications director of the California Democratic Party, John Vigna.

So … what happened with the tweet?

Eric runs his Twitter account like most folks. It’s there for sharing these kinds of thoughts. And sometimes these thoughts take on a dimension that we don’t quite anticipate when we share them.

It didn’t come from the party account, and it’s not a statement of party policy. He wasn’t calling for an official boycott, he was just expressing his own personal opinion.

Bauman now says he isn’t even personally boycotting In-N-Out. If it wasn’t a party position, and it isn’t going to inform his personal actions, what exactly was being signified?

If we take away the word boycott, it’s an expression of personal displeasure that a company he likes was donating to a party that hates him as a human being. He’s a gay, Jewish man who used to be a labor organizer.

It was ultimately an expression of personal disappointment, and I think reflects the feelings of a lot of folks who were disappointed to learn that. The word “boycott” obviously took on a very different connotation to a lot of people, but at its core it was ultimately just a statement as a consumer and a Californian in disappointment that an iconic California company would make this kind of donation to the Republicans at this moment. But we’re not launching a war on In-N-Out.

In-N-Out has also donated a fair amount of money to a group that attempts to elect moderate Democrats. Did that play into the decision to walk back the boycott tweet at all?

No. In 2014, maybe somebody giving money to us would have elicited a different reaction, but that 2016 line of demarcation really has changed things. It’s no secret that In-N-Out has been donating money to Republicans. That’s been true for a while. This kind of donation to George W. Bush, or to John McCain, or Mitt Romney, would not have elicited the same reaction from a lot of folks. But, things have changed.

The average citizen doesn’t have a billion-dollar Super PAC that they can use to spend against whoever they don’t like. But, they do have the ability to say “I’m not going to shop here, I’m not going to buy these hamburgers.” It’s a way for people to feel like they’re affecting change in their day-to-day life, in a way that people weren’t really cognizant of before. It’s part of a broader phenomenon of people becoming more stridently political citizens.

(Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Why not boycott In-N-Out then, if that’s such a motivator for contemporary voters and people who weren’t previously as politically engaged?

To the average person on the left, a boycott’s not a scary word. It’s a tool for change. California would not be the place it is today without the great lettuce boycotts with Cesar Chavez. But it’s also a word that requires a lot of intensive planning and a lot of community-minded support and coalition-building. This is the trouble we’ve run into: Folks on the outside hear boycott, and they think we are getting ready to organize a massive protest, or an actual campaign. If you’re talking to just Democrats, boycott In-N-Out is not a controversial statement, but if you’re talking to a wider community—which doesn’t have that context, and doesn’t understand how Democrats would hear that from another Democrat—it does take on this added dimension.

In that last response you described a phenomenon that’s sometimes referred to as context collapse—where, on social media, you might be speaking to a particular constituency and the people who follow you, but it gets retweeted into another audience that receives it really differently. What does that mean for the California Democratic Party? Do you care what a Republican thinks about your statements and tweets? Or are you mainly trying to motivate your base?

With social media, you’re speaking mainly to the folks who are going to largely agree with you in total, or who are trying to troll you. And there are only really two ways to effectively get your message to a voter and persuade them: person-to-person phone calls, or person-to-person door knocks. Television, radio, and mass mail are at the peripheries, they affect the margins a little, but the actual persuasion business happens at the person-to-person level. Social media helps us with the folks we’ve already reached.

We did get a whole bunch of donations [in response to the boycott tweet] from folks saying “Thank you, I’m glad you’re standing up to this.” In the days after this all happened, we were getting $2,000-$3,000 a day, so it was a noticeable spike.

Do you think that some of the people who contributed to the spike in donations, maybe under the impression that Eric and California Democrats were boycotting In-N-Out, might feel misled?

I think they donated not so much because it was boycotted, but because they’re happy to see Democrats fighting back. We’re not usually the party that’s throwing hard punches like that, so a lot of folks aren’t used to seeing us being this aggressive. But Bauman grew up in the Bronx, as he likes to remind us often, so he’s not afraid to take a swing at the Republicans, even if it sometimes ends up coming back at us.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.