On April 9th, the Department of the Treasury debuted the first details of a new and far-reaching community-based tax incentive. In 18 states, newly designated zones could see a wave of new investment under a little-known provision of the recent tax overhaul.

These opportunity zones are designed to lure investment to the nation’s poorest urban, suburban, and rural communities with a powerful tax incentive. By the accounts of some experts, the program could deliver a vital injection to areas that haven’t yet recovered from the Great Recession. Yet it could also fuel gentrification in those communities where too much opportunity, too fast, has led to rapid displacement.

Nightmare scenarios under the opportunity zones program would mean tax benefits flowing to the wrong places or paying for the wrong things: Amazon receiving sweeping federal tax benefits to build HQ2 in D.C.’s Shaw neighborhood, for example, or payday lenders expanding their already substantial profile in places such as Louisville, Kentucky.

Or opportunity zones could just be, as critics contend, more of the same: the latest in a long line of economic development incentives that have failed to deliver. It all depends on how it’s implemented.

“Amazon HQ2 could figure out a way to make this [incentive] work [for the company’s benefit], potentially,” says Brett Theodos, a principal research associate for the Urban Institute. “Which is why zone selection matters so much. If we get places that really need the investment, it’s more likely those benefits are going to accrue to low- and moderate-income people.”

Congress created the bipartisan opportunity zones program as part of the tax bill passed last December. It’s an effort to try to rip up the stagnant and uneven pattern of economic development across the country, conditions that are dark and worsening. Even as the Department of the Treasury confirms the remaining zone designations—for 32 more states, the territories, and the District of Columbia—leaders are hammering out the terms for “opportunity funds,” vehicles that will allow investors to defer their tax liability by investing equity into a number of different kinds of assets within a community. Final nominations for opportunity zones were due to Treasury on April 20th.

The test of this program may be two-fold: first, whether cities and states pick the right places to be opportunity zones; and second, whether their federal partners set the proper guidelines for transparency and accountability.

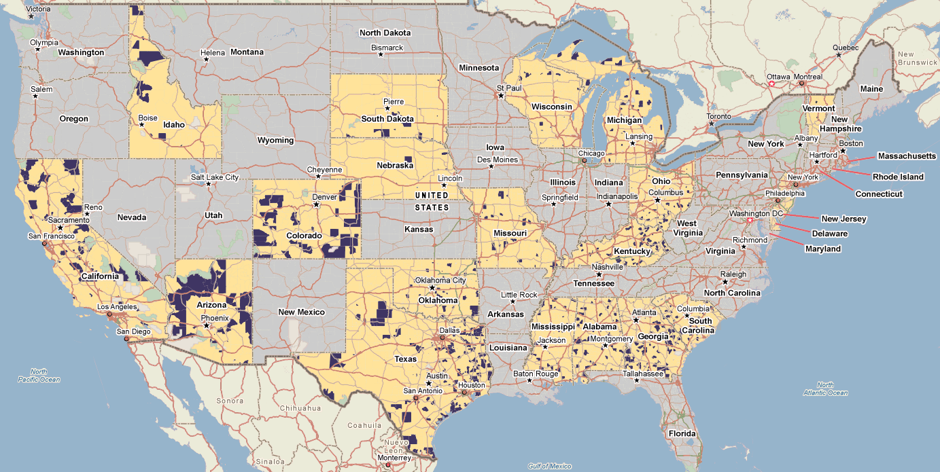

(Map: PolicyMap)

Across the nation, a huge gob of census tracts were eligible to be designated opportunity zones—41,201 in all. (That’s a bit more than half of all the census tracts in the country.) State and territorial governors (plus the mayor of D.C.) were limited to picking just one-quarter of their eligible tracts to be opportunity zones. Unlike with Empowerment Zones, a more top-down Clinton-era predecessor, opportunity zones leave a great deal of discretion to state and local leaders as to where to steer the incentive.

“We don’t have a lack of capital in the U.S. We have a lack of connectivity,” says Bruce Katz, who until recently served as a scholar for the Brookings Institution. “We have a matching problem. This incentive might accelerate our ability to match up.”

Katz is not a disinterested observer. He recently teamed up with Jeremy Nowak—a fellow at Drexel University’s Lindy Institute for Urban Innovation and Katz’s co-author for The New Localism: How Cities Thrive in the Age of Populism—to launch a consultancy related to opportunity zones. This work is taking them across the country to talk with leaders and investors alike about the program. Consider them matchmakers.

In Louisville, for example, that might mean turning an under-used high school into a vocational training facility. That’s one idea for an investment opportunity in Louisville’s historically black, near-downtown neighborhood of Russell, where Katz says he talked about the possibility with a school superintendent. A program to boost on-boarding makes sense for Russell (and for Louisville, and for Kentucky as a whole, and really, for America). The idea is that new investments will work hand-in-hand with other factors—assets, existing programs, benefits, local conditions—to generate new jobs and also produce new skilled workers to fulfill those jobs.

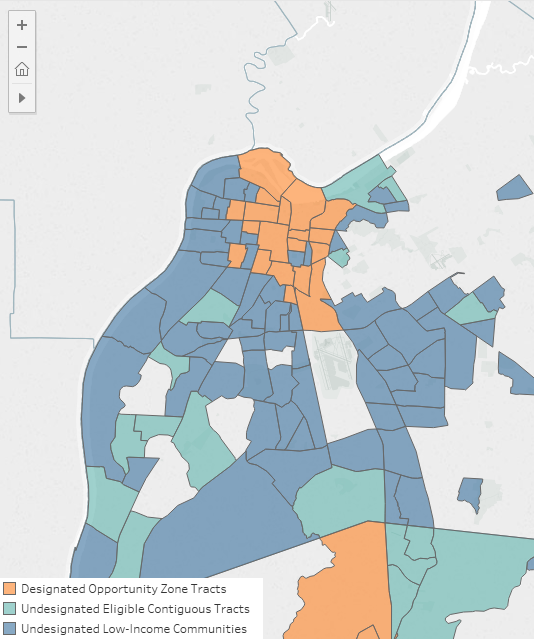

Below is a map showing Louisville’s opportunity zones, courtesy of a tool built by Enterprise Community Partners. The opportunity zones designated by the state appear in orange. Russell, just west of downtown Louisville and across the highway that segregates the city racially and economically, is among the designated zones.

Other areas that meet the main criteria for eligibility but haven’t been designated are shown in blue. These are Low Income Community census tracts: areas with either a poverty rate of at least 20 percent or a median family income less than or equal to 80 percent of the area median income. Some tracts are eligible because they are adjacent to Low Income Community census tracts, even though they don’t have quite the same poverty profile; rendered in green, these contiguous tracts can make up only 5 percent of a state’s nominated zones. (Another 200 select tracts around the nation with especially high migration rates or low population levels were also granted special eligibility.)

In a month, Treasury will release the final opportunity zones. These designations will last a decade, meaning that decisions by state and local leaders will determine the fate of the federal program. That’s key in differentiating opportunity zones from the New Markets Tax Credit: Local governments get say. Only one-quarter of eligible tracts will be open to opportunity funds. Local stakeholders’ decisions in choosing between qualifying tracts will be especially consequential.

“There’s a lot of variation in how much capital the qualifying census tracts are accessing,” says Theodos, who led a project at the Urban Institute to show where opportunity zones could do the most good (and where they might not). “That means that some places need the incentive more than others, and that ranges of course across place as well. The governors have a lot to choose from, and their choice matters quite a bit.”

The program’s authors say that opportunity zones can offset a tilted economy. At a time when inequality is practically a new national anthem, access to capital is especially skewed, geographically. Whole swaths of the nation have seen a decline in large banks lending to small businesses or opening new branches. Smaller and regional banks have struggled to keep up with the majors (or they’ve been absorbed by them). In some places, banking disparities are the result of racial discrimination, while other areas are just being left behind.

At the growth end of the spectrum, venture capital is highly concentrated in a handful of metro areas, and so is high-wage job growth. Sacramento, Philadelphia, Buffalo, and Hartford have lost high-wage jobs to Austin, Nashville, and Denver. Growth in places hit hardest by the Great Recession—in cities such as St. Louis, New Orleans, Rochester, Columbus, and beyond—is mostly confined to low-wage sectors.

“Given the trends we’re seeing in the economy, this is the right time and a necessary time to be re-evaluating the policy toolkit that we use to address economic disparity at the community level and the regional level,” says John Lettieri, co-founder and president of the Economic Innovation Group, the think tank that helped to write the legislation. “The toolkit we use now does not equip us very well to deal with the trends that we’re seeing, which don’t look anything like the trends we saw in the 1990s or 2000s.”

Here’s how the incentive works: Individual or corporate investors can defer their capital gains on investments in opportunity funds for a certain number of years (and in limited cases, permanently). The asset classes in opportunity funds are broad and flexible, with few set parameters: think affordable housing, real estate, infrastructure, and even transit. Cities, suburbs, rural enclaves, and regions can establish their own opportunity funds to identify needs ranging from hyperlocal (small businesses) to intra-state (transit).

The new tax incentive is not a strategy by itself, Lettieri says. The fact that states need to “down select”—or narrow down a list of many eligible tracts to final nominated zones—was baked into the legislation. The program will only work as well as local and state leaders plan it to work. There’s nothing preventing a state from parceling out its opportunity zone incentives to places that are already gentrifying, as appears to be the case in Cleveland.

“The opportunity zone incentive is not a silver bullet,” says Steve Glickman, co-founder and chief executive officer of the Economic Innovation Group. Cities like Louisville have a few different kinds of urban markets to consider. There’s the medical district on the east end of downtown, which works like an innovation district. There’s the area of the city near the University of Louisville that has a strong engineering focus. The near-in but economically fenced-off west end is another typology—but it’s an area that the market has historically ignored or discounted or failed to appreciate.

The promise of opportunity zones is that self-selecting communities can identify their assets and signal their potential to investors. An opportunity fund that drives investment into small businesses and real estate into neighborhoods like Russell in Louisville could be a model for opportunity zones in other cities that are similar to Russell (and vice versa). The same way that innovation districts and anchor institutions resemble one another (as markets) from one city to the next, so will the to-be-determined opportunities in distressed communities—from South Bend to Louisville to St. Louis and beyond.

“[The market]’s going to begin to understand that the country has these typologies, has these categories, of different kinds of geographies and assets which then lend themselves to certain kinds of investment,” Katz says. “It’s not like, at the end of the day, we’re dealing with hundreds of radically different kinds of propositions. I think this is going to be a market that routinizes.”

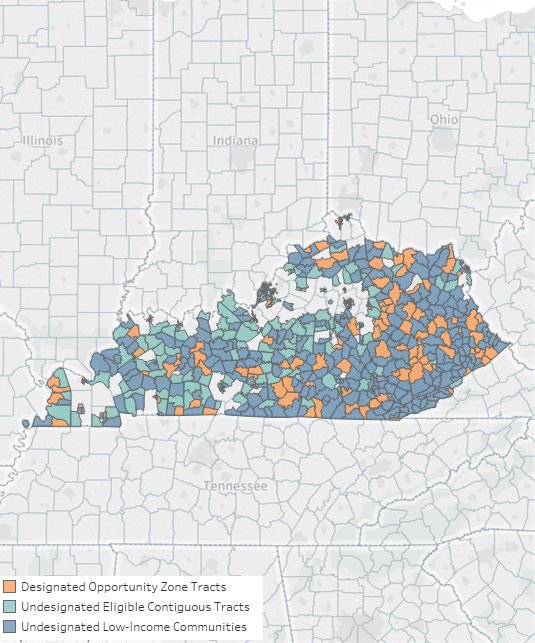

Kentucky’s opportunity zones cluster in urban tracts in Louisville, Lexington, Bowling Green, and outside Cincinnati. But many more eligible tracts (and opportunity zones) fall in exurban and rural areas—places where the reach of banks is declining, job growth has fallen off, and home mortgages are more likely to be under water. Much more of the country looks like these places than like the white-hot markets of Boston, New York, San Francisco, Seattle, and Washington, D.C.

(Map: Enterprise)

Whether the opportunity zones program can avoid the mistakes of “empowerment zones” and other place-based incentives depends on what places leaders pick. In Texas, for example, San Antonio Mayor Ron Nirenberg submitted 27 tracts for consideration to the state: a few downtown but most of them stretching further out into Bexar County. (Texas Governor Greg Abbott included 24 of them in the state’s final 628 nominations.) Knowing whether Nirenberg called it right means weighing a host of thorny factors related to race, class, blight, potential employment centers, and more.

Socioeconomic Change Red Flags

For the Urban Institute, Theodos’ team charted various kinds of capital flows for every eligible opportunity zone tract out there. The project assigned each tract an investment score, a value based on four factors: commercial lending, multifamily lending, single-family lending, and small-business lending. Tracts with a high ratio of investment in one or all these categories earned a high investment score. At such a small geographic level, a high score can sometimes reflect a skewed reality: a concentrated share of low-income housing, for example, or a prison construction project.

Theodos also generated a “socioeconomic change flag” as a measure of demographic change in every tract.

Put simply, it’s an indicator for gentrification. Tracts that earned a flag have showcased enough socioeconomic growth already that they don’t need economic stabilization. For these neighborhoods, opportunity zone designation could mean property tax shocks, luxury development, displacement, and all the other undesirable effects of geographic disparity that the program is trying to solve.

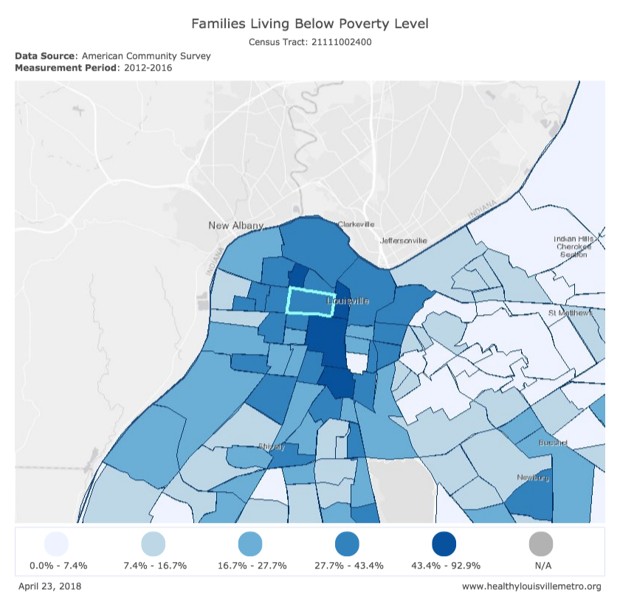

In Louisville, the census tract that matches up with Russell—where investment might take the form of a new vocational school—has an investment score of nine (out of 10). That means a high level of existing investment, mostly in small businesses (which may reflect the $29.5 million that the neighborhood received through another federal program, the Choice Neighborhoods Initiative). Only one of the eligible tracts for Jefferson County (i.e., Louisville) earned a socioeconomic change flag, the gentrification bat-signal in Theodos’ analysis. Kentucky leaders skipped this tract, although they designated almost all of its neighbors as opportunity zones.

(Map: Healthy Louisville Metro)

In some urban areas, it may be hard to designate opportunity zones without running the risk of transforming the neighborhood. For example, nearly every census tract in Baltimore City qualifies as an eligible low-income tract, but large parts of Baltimore definitely do not lack for private investment. By the Urban Institute’s measure, nearly 20 percent of Baltimore City tracts are already gentrifying. A tax incentive for investors to build up areas like Fells Point or Station North—the places where investors are happily building already— will do the opposite of what the program’s framers intended.

“Those communities that have experienced a lot of social change, it may well be that low- and moderate-income residents are not able to remain and benefit from the incentive,” Theodos says.

Treasury has not yet released Maryland’s designations. Same with Washington, D.C., a unique city-state with no rural areas within its 68-square-mile boundaries. Almost half of the District’s opportunity zone–eligible tracts got Urban’s gentrifying marker. The new tax incentive could carefully guide investment toward the parts of the city where it is still badly needed, or it could pour gasoline on a market that’s already white hot.

“I think it’s all over the place. I saw a few instances in which states seemed really sophisticated and knew what they were doing,” Nowak says. “They’re grappling particularly with what urban areas can grow, and really grappling with the rural issues, which are really hard. Then I saw other examples where states just said, ‘Give us your tracts, we’ll use those and see if we can get them all in.'”

A Federalist Approach

Even as the administration is still mapping out where the nation’s opportunity zones will go, policymakers and stakeholders are puzzling out what opportunity funds will mean to investors. Lettieri and Glickman say that the breadth of possibility for Opportunity fund investments is critical to ensuring that it works as an incentive for struggling communities across urban, suburban, and rural settings. The same tax incentive might build workforce development in rural Appalachia or affordable housing in downtown Atlanta.

“If these projects are used broadly to accomplish social good, to build affordable housing, to create new businesses and help businesses expand, then this program will be able to create a new ecosystem of community development financial institutions and equity investors coming together to support businesses and developers to do work,” Theodos says.

“Alternatively, if it’s used by payday lenders to grow their payday footprint, that might have a different effect on the local community,” he adds.

But the upside is substantial too. Nothing in the United States serves quite the same role as, say, Sweden’s Kommunivest, a consortium that enables municipal governments to raise capital by issuing green bonds. Done right, opportunity zones could serve an unfulfilled intermediary role between capital and places where capital has evaporated.

The problem is larger than a missed marketplace opportunity. Economic anxiety in America is linked to sincere systemic problems, from lifetime earnings gaps to lower childhood achievement gaps to higher suicide rates. “Worst of all, the longer the unemployment spell, the less likely the possibility of reemployment—and by extension the opportunity to escape these terrible costs—becomes,” reads a white paper by Jared Bernstein and Kevin A. Hassett. The Economic Innovation Group released the bipartisan paper in 2015 as its mission statement for opportunity zones.

Depending on what local and state leaders do with it, the program may exacerbate some of the problems stemming from growth in high-octane areas. But there are worse problems, and those are the ones that opportunity zones were designed to target.

“I think cities, counties, and states are grown-ups,” Katz says. “Let’s take [this program] at its word and see if we can—in a classic, American, federalist, distributed way—figure it out.”

This story originally appeared on CityLab, an editorial partner site. Subscribe to CityLab’s newsletters and follow CityLab on Facebook and Twitter.