It can be tough being a human in a machine’s world. Over six months, my colleague Luke Stark and I have been studying how workplace automation affects Uber drivers. What we’ve found, in online forums and interviews, isn’t always pretty.

Alex Rosenblat is a researcher and technical writer at Data & Society, a New York organization focused on social, cultural, and ethical issues arising from data-centric technological development.

Uber clearly benefits many riders, who can command a car with ease from their smartphone. Riders often pay less than for a taxi, and they can easily give feedback about the driver. For drivers, it’s easy to get started, the hours are flexible, and the pay can be satisfying.

But Uber’s emphasis on managing remotely can raise issues of fairness. Rather than having managers who listen to them and deliver feedback, drivers are managed through monitoring and rating systems delivered by semi-automated messaging. Uber says it’s just an app, not the drivers’ employer. Yet, this claim belies the significant control Uber exerts over their behavior through electronic management and performance metrics.

From Uber’s perspective, drivers are a stopgap solution until autonomous vehicles can replace them. The more permanent Uber employees—the data scientists—algorithmically scrutinize the drivers’ movements to determine where they should be positioned to meet passenger demand. At Uber, drivers are also data points on a screen. The data they generate as they do their work feeds Uber’s surge pricing algorithm, can help determine how long it should take a driver to complete a trip, or could be used to move into markets beyond passenger delivery.

Drivers are shown incentives to re-position themselves accordingly, such as surging prices in passenger hot spots or guaranteed minimum hourly rates if they drive in particular places at peak times and meet certain conditions, like a high ride-acceptance rate.

Uber controls the fluctuating pay rates drivers receive for their work as well as the system by which they are rated. It also rewards and penalizes drivers based on implicit and explicit rules, promulgated through routine and automated messaging.

The company monitors how often drivers accept passengers, how often they cancel rides, hours spent logged in to or out of the app, the ratings they receive and give to passengers, and feedback from passengers. Uber sends routine messages warning drivers if their acceptance rates are too low (such as less than 90 percent) or their cancellation rates are too high. High performers are praised while low performers risk deactivation with no definitive recourse. Some drivers take a class that Uber suggests and apply to be re-activated.

But the contexts of a low ride-acceptance rate or a high cancellation rate are not taken into account. There’s no flexibility for when accepting a ride would mean the driver actually loses money, let alone a mechanism for indicating when passengers are behaving badly. Drivers can report these circumstances to Uber, but, according to drivers, Uber will not remove bad ratings from a driver’s record, even if they received them unfairly. (The company did not respond to four requests for interviews or comments since early July.)

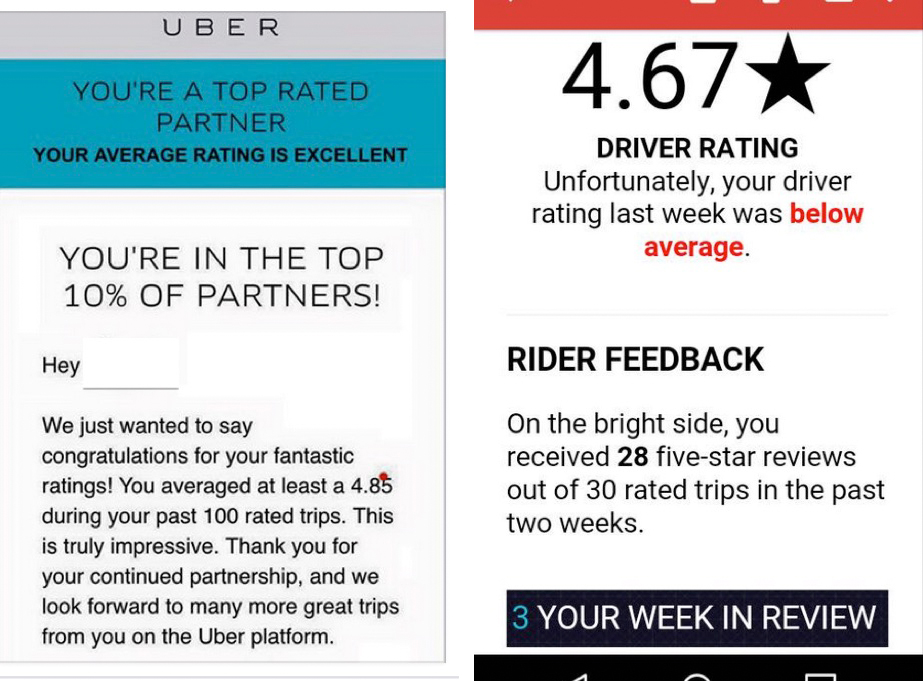

Here are two sample messages drivers receive from Uber:

The only way for Uber drivers to contact the company for help is through email. While the responses often arrive quickly, they are typically stock responses. Some drivers perceive that their questions don’t reach a human community support representative (CSR) until several emails in. Drivers have started referring to these respondents as “Uber’s robots.” So much for the nuanced, understanding relationship between a human boss and human workers.

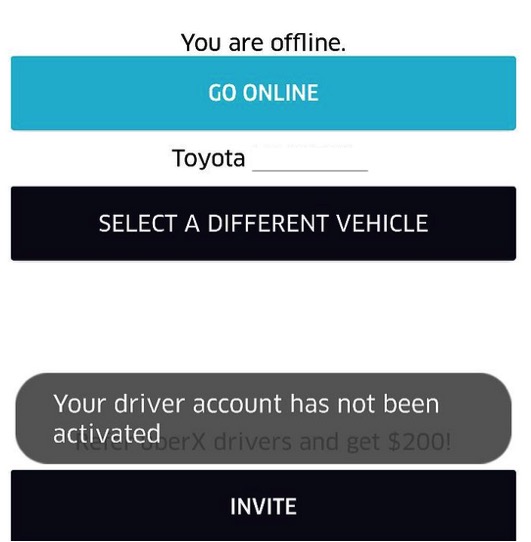

Drivers out of compliance with soft and hard rules aren’t fired. Instead, their vehicles become inactive in the system, or they see a log-in error when they try to start the app. Usually, they receive a text or an email that they’ve been de-activated but the notice may not contain an explanation. This is what one driver saw after being de-activated:

The fired driver is still prompted to invite other drivers to join the service to receive up to $200. In some situations, drivers can apply to be re-activated after they email Uber CSRs to identify and resolve the reasons for de-activation.

Passengers occupy the role of middle managers: they watch their requested driver approach the pick-up point, and the view they see on their Uber app map displays an estimated time of arrival and a route without any obstacles, such as traffic, pedestrians, or lights. So the passenger waiting for his ride might grow frustrated, and give the driver a lower rating.

Some drivers perceive this system as fairer because the rating of any one angry customer is balanced against the judgment of all the others. As one driver we interviewed said, “It’s so much better to have 100 managers than one who maybe doesn’t like you because he hates your hair.”

Passengers are prompted to rate their drivers on a scale of one to five stars, and Uber averages the last 500 ratings drivers receive to rank them against other drivers. But Uber does not educate passengers on what the rating should reflect, nor does it offer suggestive categories, such as “safe driving” or “clean vehicle.” Yet drivers’ job eligibility depends on this rating system.

Although the cutoff point varies according to how other local drivers perform, the general guideline is that drivers whose rating drops below 4.6 risk de-activation. Some get notices if their last 50 ratings are too low, rather than the last 500. Many say they receive poor ratings because of, say, surge pricing or passengers unhappy because they were forbidden to cram in more passengers than there are seats, or drink alcohol.

In effect, the drivers become the sponges that absorb the blame for problems beyond their control through Uber’s rating system. Drivers try lots of strategies for getting better ratings, like offering snacks and water, or apologizing for surge prices.

Even as it asserts significant controls on how the drivers do their jobs, Uber maintains that they are independent contractors—“driver-partners”—and avoids the mutual obligations that an employer-employee relationship entails. Drivers don’t necessarily want to be employees, but a third category of employment may develop around flexible workers who value control over their schedule. This category should acknowledge the power of automated systems to control how workers do their jobs.

In a system of digitally mediated employment, workers need to be empowered to hold automated systems accountable for fairness. Drivers would benefit, for example, from the ability to negotiate rate raises or guarantees. Uber gives notice to drivers when they change rates, but drivers can’t negotiate for higher rates.

There is no in-app feature for drivers to accept tips, and Uber strongly discourages the practice of tipping. But drivers’ top complaint is that they don’t get tips. Some passengers give cash anyways, and some drivers use Square to accept credit-card tips.

Drivers could also benefit from increased passenger education on what ratings mean. Drivers are rated on a one-to-five basis, but they generally need to maintain at least a 4.6/five. Yet, most passengers assume a four is good, even though it’s actually a failing grade.

Many drivers assert that the email replies they receive from Uber often contain inaccurate or incomplete information, or lack a nuanced understanding of the challenges drivers face. Drivers could benefit from more reliable information management about their work from Uber.

We need a better reckoning of what kinds of protections need to be in place to make remote labor management sustainable for flexible workers. Giving drivers’ a stronger voice in the machinery is a good start.

For the Future of Work, a special project from the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences at Stanford University, business and labor leaders, social scientists, technology visionaries, activists, and journalists weigh in on the most consequential changes in the workplace, and what anxieties and possibilities they might produce.