For more than two decades policymakers have struggled with the twin challenges of stagnant household incomes and sluggish job growth. Data from the Department of Labor shows that real median incomes are down 7.2 percent since the turn of the century, while labor force participation is at a four-decade low. These are challenges that disproportionately affect middle-class Americans—because while it is true that the United States economy has grown significantly since the Great Recession, most people have yet to feel the benefits.

Travis Kalanick is CEO and co-founder of Uber.

This is where companies like Uber can help. We’re often said to be part of the on-demand economy because anyone can now push a button and get a ride. But another benefit of the on-demand economy is that people can work whenever and wherever they choose. The ability to push a button and get work—earning an additional $1,000 or $3,000 a year—can significantly improve the quality of life for many families. It might be the difference between a vacation and a “stay-cation,” or perhaps a better Christmas for the kids. There’s also the extra security from being able to work here and there to make ends meet. Research by the Federal Reserve has found that 47 percent of people in the U.S. would struggle to handle an unexpected bill of $400—with a third saying they would be forced to borrow.

This kind of flexible work, that fits around people’s lives, has traditionally been hard to find. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, around 20 million Americans work fewer hours than they would like for “non-economic reasons.” These include personal commitments, in particular child care, that can make full-time jobs so difficult. In fact, it may be getting harder to find flexible work that does not conflict with existing obligations. A study by the University of Chicago found that half of all hourly workers now have no input at all over the schedule set by their employers. It’s part of a move away from giving employees predictable shifts. Instead, companies keep them on call, bringing people into work for fixed periods with little notice when demand is high.

Uber works in a very different way. People decide where, when, and for how long to drive. They are free to turn off the app and stop working at any moment. In other words, their needs determine their work schedule—and nothing else. Nearly 90 percent of all drivers say this is a major reason to work with Uber: it’s about being their own boss. In fact, three out of every four drivers say that, if given the choice between a nine-to-five gig and more independent work like Uber, they’d opt for the independence.

It’s easy to see why. People can choose to work for a couple of months to pay the bills as they transition their career or for just a few hours to fund a kid’s soccer class. Fifty percent of people drive less than 10 hours each week—that’s not even what we think of as a traditional part-time job. What’s less obvious is that the people who spend most of their time driving with Uber seem to value this flexibility and independence as much as, if not more than, the majority who drive just a few hours each week. That’s because a typical 40-hour job rarely offers the ability to visit an elderly parent, go to a job interview, or tend to family emergencies without asking for permission beforehand.

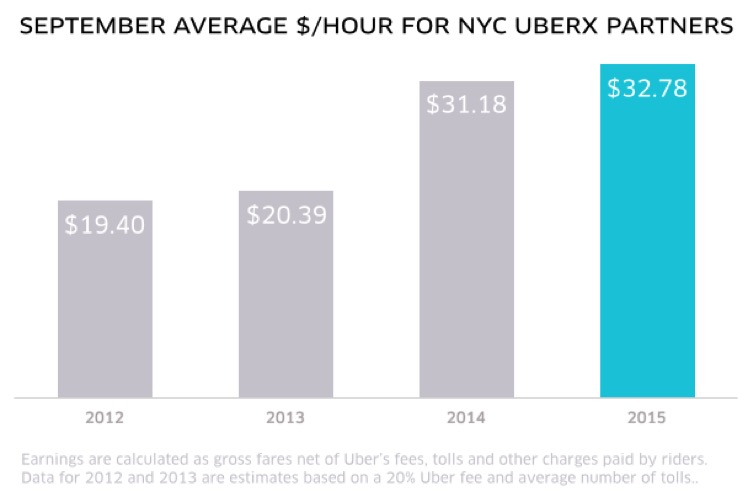

At the touch of a button, on-demand platforms can now connect workers with a huge marketplace of customers right away. And if something more important comes up, these workers can simply turn their work off. It’s a tremendously efficient use of their time—and we’re working hard to make it even more efficient by reducing the waiting time between trips. In New York, for example, the average amount of time drivers spend each hour with a passenger in the car (that’s when they are earning) has doubled in the last four years. The end result: more reliable earnings because there’s less dead time, as this chart shows.

A decade ago, opportunities to find flexible work were limited. I know because I was living with my parents trying to make ends meet as a struggling entrepreneur. But when our millionth driver took his first trip with Uber a few months ago, I realized that on-demand companies are pointing the way to a more promising future, where people have more freedom to choose when and where they work. It’s a shift that will help give families more control and security over their lives. Put simply, the future of work is about independence and flexibility.

For the Future of Work, a special project from the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences at Stanford University, business and labor leaders, social scientists, technology visionaries, activists, and journalists weigh in on the most consequential changes in the workplace, and what anxieties and possibilities they might produce.