Prime Minister Narendra Modi has launched a manufacturing-focused campaign called Make in India as the primary driver for economic growth in India. I believe this is a misdirected allocation of resources, based on a policy rooted in growth models reminiscent of the 20th century. India is perfectly poised to be the innovation bedrock of the world. An “Innovate in India” campaign would better reflect the aspirations of the new generation.

Amita Katragadda is a practicing attorney in India and a former partner at Amarchand Mangaldas, India’s largest law firm. She has an MBA from the Stanford Graduate School of Business.

Modi’s Make in India is a here-and-now strategy aimed at increasing manufacturing’s share in GDP from a stagnant 15 percent to 25 percent. It is a large program, comprising infrastructure investments, skill development missions, subsidies, tax incentives, and systemic changes to increase the ease of doing business in India—aimed toward generating employment opportunities for India’s substantial young labor force. I would argue that its benefits are, at best, ephemeral. Historical and current trends have shown, for example, that employment in China’s manufacturing has been deeply hurt by mechanization and competition from other economies offering cheaper labor. For instance, Foxconn is increasingly mechanizing its manufacturing process, leading to significant layoffs of Chinese labor. Similarly, Nike has moved its manufacturing to Vietnam and Bangladesh on account of cheaper labor access. The environmental issues of big manufacturing also demand serious consideration.

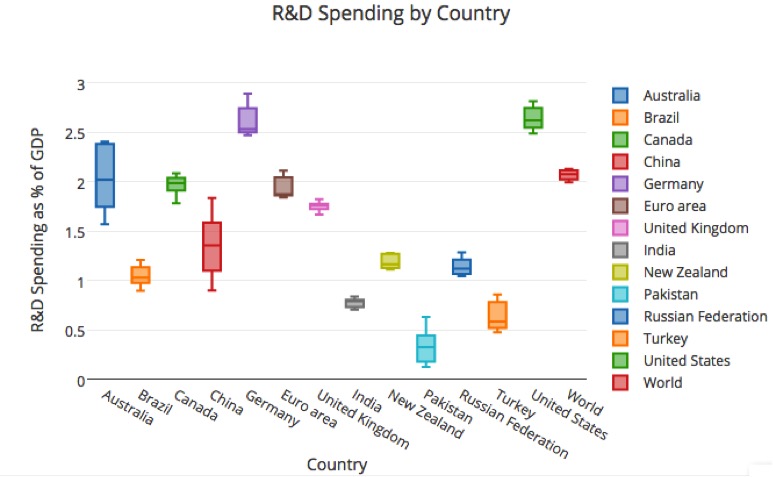

In sharp contrast to the significant monetary and infrastructure commitment made toward the Make in India campaign, India currently spends 0.7 percent of its GDP on research and development. This is less than half the world average, and significantly lower than the countries with which India believes itself an economic peer. For a country that boasts a young labor force and some of the world’s best technical education, this is a disturbing metric. However, it offers a significant and potentially effective opportunity for Government intervention.

Currently, world over, high costs of R&D and innovation are encouraged and forgiven since they can be recouped through high prices under patent protection. These high prices keep innovations out of reach of low-income households. What the world needs is lower-cost R&D, resulting in lower prices and higher access to innovations. This is where India, with its population, its position in the world economy, and its deep culture in technical training, can bridge the global gap for low-cost R&D and innovation. It could also shine the R&D spotlight on needs that are not a priority of Western innovators.

Innovation and the creation of new ideas also make it possible for finite resources to support a larger population. Macroeconomic theory has time and again shown that the execution of new ideas leads to sustained growth of income per person. Because of their ‘‘non-rivalrous’’ nature, ideas are exempt from the diminishing returns that usually plague capital investments. In this model, economic growth depends on the generation of ideas, which in turn depends on the number of innovators. What India needs for economic growth, then, is to bring more people into an innovation mindset—cutting across sectors from rural to rocket science.

This mindset already exists in pockets. Stories about cost-conscious innovation span the Indian sub-continent. Mansukhbhai Prajapati lost everything in the 2001 Gujarat earthquake. He re-started his life and built a low-cost clay refrigerator that does not require electricity. The refrigerator was launched into commercial production in 2005; he has since developed a range of earthen kitchenware. Mansukhbhai epitomizes the adage ‘‘necessity is the mother of invention.’’ He pulled together traditional knowledge and easy-to-find raw materials to build the next generation of sustainable kitchenware. At the other end of the spectrum, the Indian Space Research Organization in 2014 launched India’s first Mars satellite, at less than 11 percent of the cost of NASA’s Mars mission.

Technology and other global advances have significantly reduced the costs for core innovation. And now smart innovations can plug into any ecosystem. Innovators need no longer be geographically based in the target market. Entrepreneurs in Israel, for instance, are solving the needs of a global audience.

These are some of the reasons India should define itself as an innovation economy. It can ride the growing demand for innovators and cost-conscious innovation to challenge innovation hubs of the West. An Innovate in India campaign could invest in labs and incubators; make R&D grants; provide incentives for foreign companies to set up their R&D centers in India; build innovation-driven education; extend systemic support for scalability and adaptability of innovations through capital, technical, and strategic contributions; convene technical conferences that bring together breakthrough inventions; and integrate legal systems that will protect and hold innovators accountable.

Prime Minister Modi has the power to re-invent how every Indian thinks of herself. A strong message from him could be the fastest route to moving a significant populace into an innovation mindset. This is the future of India, and also the world.

For the Future of Work, a special project from the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences at Stanford University, business and labor leaders, social scientists, technology visionaries, activists, and journalists weigh in on the most consequential changes in the workplace, and what anxieties and possibilities they might produce.