What makes Keith Wallach’s apartment extraordinary is not the least bit evident at first. The kitchen of his lower Harlem studio is diminutive but tidy. The furnishings — a queen-size bed, a considerable couch and a bureau — dwarf the space but look nearly new. Surfaces are cluttered in a way that suggests once something is put down, it stays there for years. Yet the place is clean. In fact, the most remarkable attribute of Wallach’s home is that he is in it, because for years he was part of a small but conspicuous segment of the population: People who live on the streets, suffer from severe mental illness, resist all services and are considered intractably, eternally homeless.

Wallach is a balding, pudgy, healthy-looking 48-year-old. He’s quite personable but doesn’t go out much and steadfastly avoids eye contact, symptoms of his paranoid schizophrenia. When he is asked his opinion of the apartment, the response is emphatically, typically New Yorker. “It’s all right,” he says like a seasoned tenant, following up with a couple of chestnuts about the dangers of his neighborhood and a noisy upstairs neighbor.

In a few crucial ways, the apartment isn’t just all right but extraordinary. First, it is not temporary or transitional. It comes with formidable support — an array of professionals and services he can access. And he was handed the key to the apartment without preconditions. That was nine years ago, making him one of the earlier beneficiaries of a radical new approach to chronic homelessness that has proven astonishingly successful.

The term “chronically homeless” has a government definition, but in colloquial terms it refers to a small but hard-to-reach subset of the homeless, people who are dirt-poor, cut off from family and some combination of mentally ill, rabidly alcoholic, perilously abusive of drugs, physically disabled and recurrently sick. These are far and away the most visible of the estimated 800,000 homeless people in the nation, but they are not the poster children of homelessness. They’re mostly adults, to begin with. They’re often missing teeth, bruised, disfigured, unkempt, pungent and loud, sometimes abusive or threatening. They are also part of a nationwide trend that has seen their numbers diminish — in fact, plunge — for perhaps the first time in the nation’s history. For two years (the only two years for which there are national data) the chronically homeless population has decreased, going from some 175,000 in 2005 to less than 125,000 in 2007.

Few in the field believe that the national numbers are precise. “Counting the homeless population is notoriously difficult,” says Paul Koegel, a behavioral scientist at the RAND Corporation who began research on homelessness 25 years ago. Methodologies have changed in some communities in the last few years, for one thing, and most of the numbers come from “point-in-time” counts rather than databasing methods that track homeless populations over time.

Nevertheless, there is overwhelming agreement among providers, advocates, academics and government officials that the reduction in chronic homelessness is no artifact of statistical voodoo by the Housing and Urban Development bureaucracy but real and considerable. “The trend and magnitude are well supported,” says Nan Roman, executive director of the country’s oldest advocacy organization in the field, the National Alliance to End Homelessness.

There is one major reason for that trend: From the federal down to the local level, hundreds of service providers and government agencies have embraced a groundbreaking approach that greatly reduces — and might eventually all but eliminate — chronic homelessness.

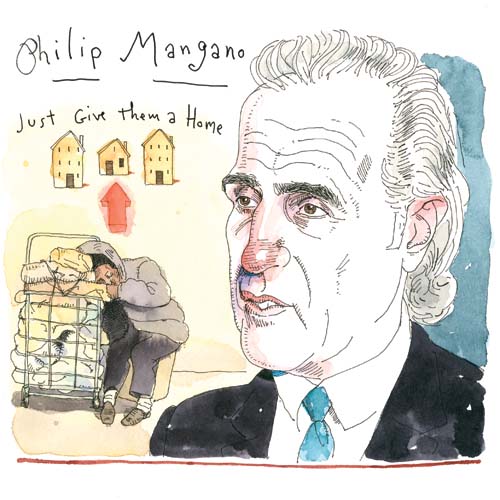

Of course, it took a legion of committed people standing on the shoulders of many more to develop and implement the model, but three — common-sense clinician Sam Tsemberis, on-the-ground numbers guy Dennis Culhane and chief franchiser Philip Mangano, a federal appointee with a knack for persuasion — are generally credited as the fundamental innovators. Each contributed a critical piece of the successful approach to the problem.

“What Sam, Dennis and Philip have done is develop a research-based, outcome-oriented model that truly works in getting the chronically homeless off the streets and into housing,” says Jamie Van Leeuwan, project manager for a 10-year plan to end homelessness in Denver.

The solution for chronic homelessness turned out to be breathtakingly simple: housing. But when the homeless population exploded in the 1980s, there were many reasons why that response was anything but apparent and plenty more reasons why it seemed unaffordable. The journey to a policy of providing chronically homeless people with their own homes, regardless of the other troubles in their lives, was winding, arduous and humbling. Nevertheless, it generated a remarkable partnership. “In a sense, it’s the perfect storm,” Paul Koegel says. “You’ve got a service model, an empirical foundation for why the service model works and a federal official who recognizes the importance and turned it into policy.”

It’s difficult to imagine the 1970s as a halcyon time, yet the housing statistics for the period show more affordable places to live than poor people who needed them. By the end of that decade, though, the housing surplus was gone, and a deficit was rapidly growing. The mainstays of affordable housing — single-room occupancy buildings, or flophouses — were torn down or converted into condos and co-ops to serve a rising population of young urban professionals. Toss in a recession, a wave of court-ordered deinstitutionalization of the mentally ill and the Reagan administration‘s cuts to low-income housing programs, and you get a real shortage of affordable housing.

“Now there’s a musical chairs analogy for all of these people on the margins — when the music stops, there aren’t enough homes,” says Roman of the National Alliance to End Homelessness. “And the least competitive become homeless.”

The least competitive tended to be those with one or more problems like mental illness, drug addiction, alcoholism, physical disabilities and no money. These became the chronically homeless — although the category would not be distinguished as such for another decade and a half.

As the number of homeless grew, the human service system responded. Feeding and shelter programs sprang up in cities all around the country. “We responded to it in an intuitive way,” Roman says. “Everyone thought it was temporary at first.”

The problem persisted, and the government targeted funds to increasingly sophisticated responses: Drop-in centers, safe houses and shelters blossomed. Emergency programs became long-term responses. But insofar as anyone could tell from the scattershot data, the number of homeless people either stayed the same or grew larger.

By the end of the ’90s, issue fatigue had rolled in. Homelessness seemed an impossible problem, and its denizens a permanent part of the American landscape. There were a few, however, who knew otherwise.

The forces that were to produce the astonishing homelessness reduction in 2007 were already at work by 1992. One of primary instigators was a New York psychologist named Sam Tsemberis. He is the founder and executive director of Pathways to Housing, a service provider that has housed and supports nearly 1,000 formerly homeless people in three cities.

It was Tsemberis — a tall, lean man with a resemblance to Billy Bob Thornton — who took the rapidly multiplying commandments of other housing programs and tossed them out. It was Tsemberis who, against traditional treatment approaches, tried giving the homeless what they said they wanted. And it was Tsemberis who devised one of the very first programs to succeed in housing the previously unreachable chronically homeless.

He called the program “Housing First.” The concept was revolutionary, simple and so obvious that it’s hard to explain why it hadn’t emerged sooner. The elegance of the Housing First model was that it had just two moving parts: Give the homeless a home. Provide them enough services so they can keep it. “Housing ends homelessness. Services keep people housed,” Tsemberis likes to say.

Providing services — a concept called “supportive housing” — was by no means Tsemberis’ invention. That model had a host of authors in the 1980s; Priscilla Ridgway, a mental health professional now at Yale University, Rosanne Haggerty of Common Ground, Sister Mary Scullion in Philadelphia and the Lakefront SRO in Chicago all developed versions of it. It was widely seen as a necessary element of any program for the mentally ill. What was new about Tsemberis’ initiative was not what it did, but what it didn’t do: make demands. This was a counterintuitive component, but it would prove to be the linchpin of success.

Tsemberis says that he came to the idea, or it to him, while he was a member of a psychiatric outreach team for the city of New York in the early 1990s. His team worked the streets trying to persuade the acutely homeless to join one of the housing programs then in place. But the programs had requirements. The specifics varied from place to place, but the fundamentals were sobriety and stability. It was what Tsemberis calls a “treatment first” approach.

The logic seemed sound. It stood to reason that addicts, alcoholics and psychotics couldn’t manage their housing needs, so anyone coming off the streets had to become sober and mentally stable before he or she would get a place.

The problem was that those most in need of housing — the mentally ill and the substance abusing — were least likely to succeed at becoming sober and stable. “Every rule eliminates a certain percentage of people who just can’t comply,” Tsemberis says. “If we required sobriety and stability of everyone living in apartments, we’d have a lot more homeless.”

By the early ’90s, Tsemberis found that many of the people he was speaking to on the streets had already been kicked out of one or more of these programs. Others were perfectly straightforward in telling Tsemberis that they weren’t interested in a program if they couldn’t have a drink or smoke marijuana. So Tsemberis decided to suspend all his preconceptions about what he thought was best and to ask people on the streets what they wanted. “We’re trained,” he says of mental health providers, “to be responsible, to make decisions, to think if people are psychotic, they’re debilitated by it. It’s the biggest error in the field.”

The reply to his question was nearly unanimous: The homeless wanted a place to live.

The collective weight of their answers sparked the idea of Housing First. “It was totally consumer driven,” Tsemberis says, “not an idea I take credit for. My only contribution was that I was willing to listen to people and try it their way.”

In 1992, Tsemberis got a $500,000 grant from the New York State Office of Mental Health and launched Pathways to Housing. It was to be a commandment-free zone. On the face of it, it seemed insane to turn an apartment over to a mentally ill alcoholic or addict without any rules. They could stay up all night and smoke, drink, snort and shoot up all they pleased.

But the program worked, in part because of human nature and in part because there actually were two rules. The first —applying 30 percent of an individual’s income to rent — was a requirement of the grant. The second was that the newly housed had to agree to at least one visit a week from Pathways support staff.

The support comes in a wide variety of forms, starting with a team of seven specialists who handle problems with substance abuse, family, employment and mental and physical health. But such bland descriptors don’t begin to capture the nuanced, comprehensive and responsive options offered.

In addition to attention and an array of voluntary treatment programs, Pathways offers classes in writing, photography and art. There is a model apartment in which living skills such as cooking are taught. When Tsemberis ushered me into the apartment, we interrupted a meeting of the science club. Some 15 clients had gathered in the living area to discuss the origins of the universe. The conversation was led by a client — who came up with the idea of a science club in the first place and was promptly put in charge of organizing it.

By almost any measure, Pathways’ Housing First approach has been phenomenally successful. More than 80 percent of those who went into the program have maintained their places for at least three years, compared to fewer than 40 percent in other programs. By way of explanation, Tsemberis invokes Abraham Maslow’s “hierarchy of human needs,” noting that the basics come before things like treatment.

“If you live on the street, safety — where you will sleep — occupies a person’s entire psyche,” Tsemberis says. “If you’re hungry and exhausted, you can’t sit still in a 12-step meeting. Once that calms down, once you house people, then they become interested in treatment. It’s human nature.”

The surprise for Tsemberis was just how capable the chronically homeless were, even those who had spent more than a decade on the streets. “People can believe they’re hunted by the government,” he says, “but they can still cook, go to the toilet, change the channels — the daily living piece is much more intact than we ever thought.”

In his Housing First initiative, Tsemberis had found a program that worked for the toughest homeless population. Now the question was: How many people needed it, and who was going to pay for housing them?

While he was a social policy graduate student, Dennis Culhane lived in the Ridge Avenue men’s shelter in Philadelphia. For a period of seven weeks, he split his time between that 300-bed shelter and another, while he collected interviews for his doctoral dissertation.

During the day, he took the denizens of the shelter to lunch and interviewed them for two to three hours at a time. By night, he endured the “oppressive control and boredom” of shelter life, with lines for every blanket, sliver of soap or blob of toothpaste that was doled out.

Because he had a car, a 20-year-old Valiant, many of the homeless would ask him for the favor of a ride. So he met the parents of one man when he gave him a lift to their apartment to pick up his work boots. Another man needed a ride to his girlfriend’s place so he could bring her money for diapers. Culhane found that most of the men were able-bodied and intensely connected to family and friends; many were concealing the fact that they were homeless.

In the process of his research, Culhane made a number of friends, and four months after leaving the shelter, he returned, eager to see the people he’d become close to. But when he went inside and looked around, he was amazed. “No one I knew was there. They had all been replaced by an entirely new crowd,” he says.

It was in this moment that Culhane realized that the homeless population was not static but dynamic, and that understanding its dynamics would be the key to solving the problem. In 1990, the fair-haired young social psychologist with a background in homeless advocacy and a facility for numbers jumped at an assistant professor opening in the University of Pennsylvania’s psychiatry department. (He’s now with the School of Social Policy and Practice.) He immediately set himself a task: figuring out just how many homeless people there were. He wanted a census.

The government and service providers had been running on guesswork. Their counts of the homeless had been done by teams that fanned out across a city for a single night, adding the number of homeless people they saw on the streets to the total in shelters. That method didn’t say anything about how many homeless people there were in a year, how long they were homeless, where they went, who they were or what they were like.

In his search for raw data, Culhane found that New York and Philadelphia could produce detailed, computerized statistics on who was using their homeless shelters. They had been required to computerize the information because the shelters received their government funding on a per person, per night basis. For Culhane, it was a gold mine.

In 1994, he came out with his census, one of three studies that would provide the country’s first accurate portrait of who the homeless were — and, ultimately, what they cost. His first study found that in a large city during the course of a year, one in 100 people experienced homelessness. The magnitude of the number stunned officials. “It got a lot of attention,” Culhane says, “including (on) the front page of The New York Times.”

His second study, published in 1998, found that there were three kinds of shelter users. Eighty percent stayed for two to three weeks, then left and never came back. These were the homeless who were solving their own problem. Among them were the people Culhane had met at the men’s shelter — the ones who, when he returned four months later, were long gone.

He found a second group, composed of about 10 percent of shelter users, who returned from time to time, especially in the winter. He classed these shelter users as “episodic.” This group was skewed toward the younger end of the scale and had a high proportion of drug use.

Then there was the final 10 percent. Those in this group had unfortunate but telling characteristics — 30 percent were severely mentally ill, 70 percent were substance abusers and about 25 percent had a physical disability or recurring illness. Moreover, they lived in shelters permanently. They were stuck. These he called the chronically homeless. One last fact about them emerged: This 10 percent segment consumed nearly 50 percent of the resources directed toward the homeless.

The findings triggered Culhane’s third study, in which he found that the chronically homeless ran up enormously high social costs. How expensive could it be to maintain someone who lives on the streets or is jammed into a shelter with cots 10 inches apart? Really expensive, it turned out. In addition to shelters and homeless programs, the chronically homeless were frequently picked up by police and paramedics. They consumed jail time, court time, time in the psychiatric unit.

But the biggest cost involved health care, which the chronically homeless usually received from the most expensive server — the emergency room. Visits to the ER were frequent, in some cases occurring several times a day. At a minimum of $1,000 a visit, it didn’t take long for the expenses to add up. Culhane’s study, published in 2001, compared the cost of an individual in supportive housing — that is, housing plus oversight and social services — with the cost of someone on the streets. He found that the chronically homeless used an average of $40,000 per year when they lived on the streets. Supportive housing cost about $18,000 a year, and those who had it used about $16,000 less in social services. Thus the net cost of providing the chronically homeless with supportive housing was about $2,000 a year.

Since then, dozens of cost-benefit studies have been done all over the country. They put social costs of life on the streets in a range of $35,000 to $150,000 per year. Supportive housing costs from $13,000 to $25,000 and substantially reduces social service expenses. The studies found that this strategy to address chronic homelessness doesn’t just break even; it can produce a huge savings.

Advocates seized on Culhane’s work, using it to lobby Congress and the White House for support. The National Alliance to End Homelessness did its own calculations. The alliance estimated that there were about 250,000 chronically homeless people in the country and that funding to house 25,000 a year was possible. So, the group figured, chronic homelessness could be eradicated in 10 years. This calculation marked the birth of the 10-year plan to end homelessness. All that was needed now was a way to fund it and to set up franchises in cities and towns across the country.

In 1982, Philip Mangano received an unforgettable lesson in business while he was in southern Mexico, smuggling food to refugees who had fled the brutal civil war in Guatemala. Because of the deplorable conditions in the camps, the Mexican government barred entry to journalists and other outsiders, but Mangano regularly sneaked provisions to the needy refugees. One day, while he was inside the camp, a United Nations supply delivery arrived; from a hiding spot, he watched Mexican troops unload the goods. Although an entire shelf in the depot was already lined with jar after jar of cooking oil, still more jars arrived in the new load. After the truck left, he asked the refugees in the camp why there was so much oil. “No one ever asks us what we want,” the refugees said. “They just make deliveries.”

“These were people who had nothing, who were desperate, and the U.N. was delivering stuff they didn’t need and couldn’t use,” Mangano says. “How insane is that?”

Mangano calls his Mexico experience a business lesson because these days he is preaching a business model as the executive director of the U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness. The council is a small federal agency that reports to the White House and is tasked with synchronizing federal, state and local government and the private sector behind a single strategy to end homelessness. He has the access that goes with a Washington address, but Mangano is nothing if not a man who likes to be on the front lines.

Energetic and trim, with the carriage and well-cut suit of an Italian fashion model, Mangano is a near constant gale of stories, statistics, history and humor — all forefronting the incontrovertible common sense, as he sees it, of ending homelessness. It is teaching and preaching with decidedly evangelical zeal, but Mangano’s message is not religious; it’s economic. Housing the chronically homeless saves money. The business approach is reflected in the language he uses: The government does not “fund” programs, it “invests” for “outcomes” that do not “serve” homelessness but “solve” it. These are “field-tested, outcome-oriented results,” and that is why everyone — especially local governments, service providers, businesses and taxpayers — needs to get on board with the plan to end homelessness.

Since he became executive director in 2002, he has been in nearly perpetual motion, visiting towns and cities all over the nation to spread the good news about solving homelessness. Becky Kanis, director of innovations at Common Ground — the nonprofit credited with housing the homeless of Times Square — refers to him as “the man who rendered himself homeless for the homeless.”

Signing cities, counties and states on to 10-year plans to end homelessness is the cornerstone of Mangano’s work. By almost any standard, he has been wildly successful. The stats have risen from zero in 2002 to a current tally of 650 communities partnered in 350 decade-long plans.

In November, Mangano is in Colorado Springs, Colo., to be with Mayor Lionel Rivera when he announces that city’s 10-year plan on homelessness. Mangano begins the day at 8 a.m. with an informal visit to the emergency room of Memorial Health System, a local hospital. In the space of 30 minutes, he talks with an operations manager, a registered nurse, a social worker and a doctor. He learns that they treat an average of 10 homeless people a day, that each visit runs at least $1,000, and that total treatment costs for the homeless are north of $5.5 million a year. He also learns that most of the treatment is detox for alcoholics; there are regulars so savvy, they look up the hospital menus and seek out the ER with their preferred food. All of this confirms what Mangano already knows, a situation well documented in other cities. The virtue of this visit: He is now armed with specfic local data, which he will employ masterfully throughout the day.

Mangano’s next stop is a meeting with Mayor Rivera and the local chief coordinator of homelessness, Bob Holmes. Holmes is the founding executive director of an agency called Homeward Pikes Peak. It’s his job to guide the 40 to 50 local agencies that serve the homeless as well as to develop the city’s 10-year plan. The three briefly work out a strategy for a scheduled press conference, and then Holmes brings up funding — that is, investment. Money is a pressing issue in Colorado Springs; very little of it comes from the state or city. The discussion of funding triggers one of Mangano’s oft repeated points: The Bush administration has increased the budget for the homeless for a record seven straight years.

Although Mangano plugs the administration that hired him, he stresses time and again that ending homelessness is not a partisan issue. “There’s no D or R, just Americans partnered to end the national disgrace,” he likes to say. There seems to be widespread agreement, even from the most progressive service providers. The ability to unite all sides in the campaign is clearly a part of Mangano’s brilliance.

Ten minutes later, the mayor, Mangano and Holmes are in City Council chambers, announcing the 10-year plan to end homelessness before a room of interested parties and the press. After a brief announcement by the mayor, Mangano launches into a half-hour, unscripted fusillade about the undeniable benefit in ending homelessness, citing his newly acquired Colorado Springs ER data.

After a brief Q&A with the local press, he heads to United Way headquarters a few blocks away, where some 20 local heads of agencies and leaders on homelessness have gathered around a conference table for a lunch meeting. Mangano delivers a remarkably consistent message, although indignation creeps into his tone as he incites them to stop serving — and start solving — homelessness. He has no patience for providers that are part of what he has referred to as “the homeless industrial complex.”

He brings to his task an insider’s knowledge. Mangano spent decades working on homelessness as an organizer and advocate and describes himself as an abolitionist. “I want to abolish homelessness,” he will often say. “I’m from Massachusetts. It’s in our blood.” It is a conscious choice to invoke the civil rights and anti-slavery figures with whom he clearly identifies. He readily quotes William Lloyd Garrison, Frederick Douglass, Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. — all part of the “long arc of moral justice” he is pursuing now for the homeless.

Mangano’s next appointment is with the editorial board of the Colorado Springs Gazette, which recently published an opinion piece with a distinctly libertarian redolence that urged local officials to stop harassing the homeless and suggested the federal government stop spending money on them, because they are choosing to be homeless.

This is an opportunity for Mangano to take on one of the most persistent myths in the public mind — that the homeless want and prefer to live on the streets. He cites a case in Seattle: 75 units of housing were made available, and providers worried that they wouldn’t be able to convince enough homeless people on their list to move in. He poignantly narrates that it took exactly 80 tries to fill them; 75 of the people on the list were willing, two had disappeared and three had died.

Apparently, all this has an impact. A week later, the paper runs an editorial headlined “Just Give Them a Home.”

Mangano is driven by the morality of ending homelessness, but his effectiveness lies in using the economic argument to persuade. He believes his argument is indisputable: “Everyone who hears the case gets it.” The fact is that an enormous number of American cities have heard the argument only because of Mangano.

It is not clear how much longer Mangano, as an appointee of the president, will be a federal employee. There is word that some of the mayors and state leaders are agitating for Mangano to have a place in the Obama administration, but his fate remained unclear in January. The presidential transition team did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

Homeless advocate Nan Roman tells a story about the first time she brought up the idea of a 10-year plan to end homelessness to her mentor, a man she describes as intellectual and thoughtful. His reaction was that it was fantastic, except he thought she should get rid of the chronically homeless piece. “‘Helping the bums on the street — it’s going to drag everything down,'” she recalls him saying.

“But just the opposite has happened — the chronically homeless is the piece that caught on,” she says. “It’s kind of amazing that it’s getting done, now that I think about it.”

Nearly every major city has posted a significant decrease in the numbers of homeless in the last couple of years: 30 percent in Miami, 28 percent in San Francisco, 36 percent in Denver. These numbers represent the trend, not exceptions to it. The credit for the reduction in homelessness goes to thousands of service providers and policy planners all over the country, yet it wouldn’t have happened without the innovation and creative implementation of Tsemberis, Culhane and Mangano. “They’ve had a huge, field-shaping influence in the way everyone thinks about what can and should be done,” Becky Kanis says.

There is no shortage of respect among the three men; Mangano and Culhane have known each other since the ’80s, when both worked on homeless advocacy in Boston. They’ve known Tsemberis since the ’90s. “Sam was the innovator,” Mangano says of Tsemberis. “And without Culhane, frankly, we’d still be lost.”

Still, no one is close to saying “mission accomplished,” particularly as the economy deteriorates. “We’re going to have a lot more homeless people,” Roman says. “That’s something, except for during welfare reform, I haven’t said since the ’80s.” Recent numbers have already shown an ominous uptick in family homelessness.

“When the economy tanks, people at the bottom feel it most acutely,” says behavioral scientist Koegel. “You don’t get much closer to the bottom than homelessness.”

There is no doubt that the nation faces hard times, but it does have a model for solving a problem that only 10 years ago was largely thought to be intractable. The end may not come as soon or as completely as many recently expected. But there is still hope that 10 years from now, Keith Wallach and 125,000 or so other formerly homeless people will be complaining about their noisy upstairs neighbors from the warmth and security of the places they call home.

Sign up for our free e-newsletter.

Are you on Facebook? Become our fan.